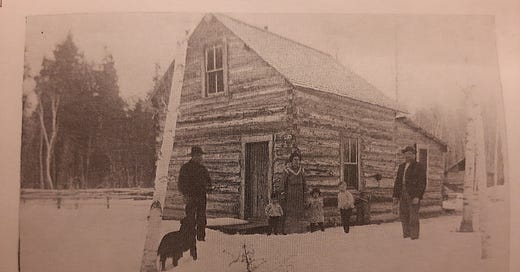

[Charlie Kling homestead c. 1908.]

I grew up thinking my great-grandparents were immigrant pioneers who staked a claim to become farmers.

Sometimes, that which we know, is found to be, quite simply, not so.

This anonymous quote appears as the epigraph in Lest We Forget, a local history of the “pioneers” who settled along Willow Creek east of Warroad on Lake of the Woods. It is written by T. E. Helmstetter (1920-2012), whose family homestead had been adjacent to the plot staked by my great-grandparents Charlie and Ellen Kling. It is one of the few books with references to my great-grandparents in northern Minnesota.

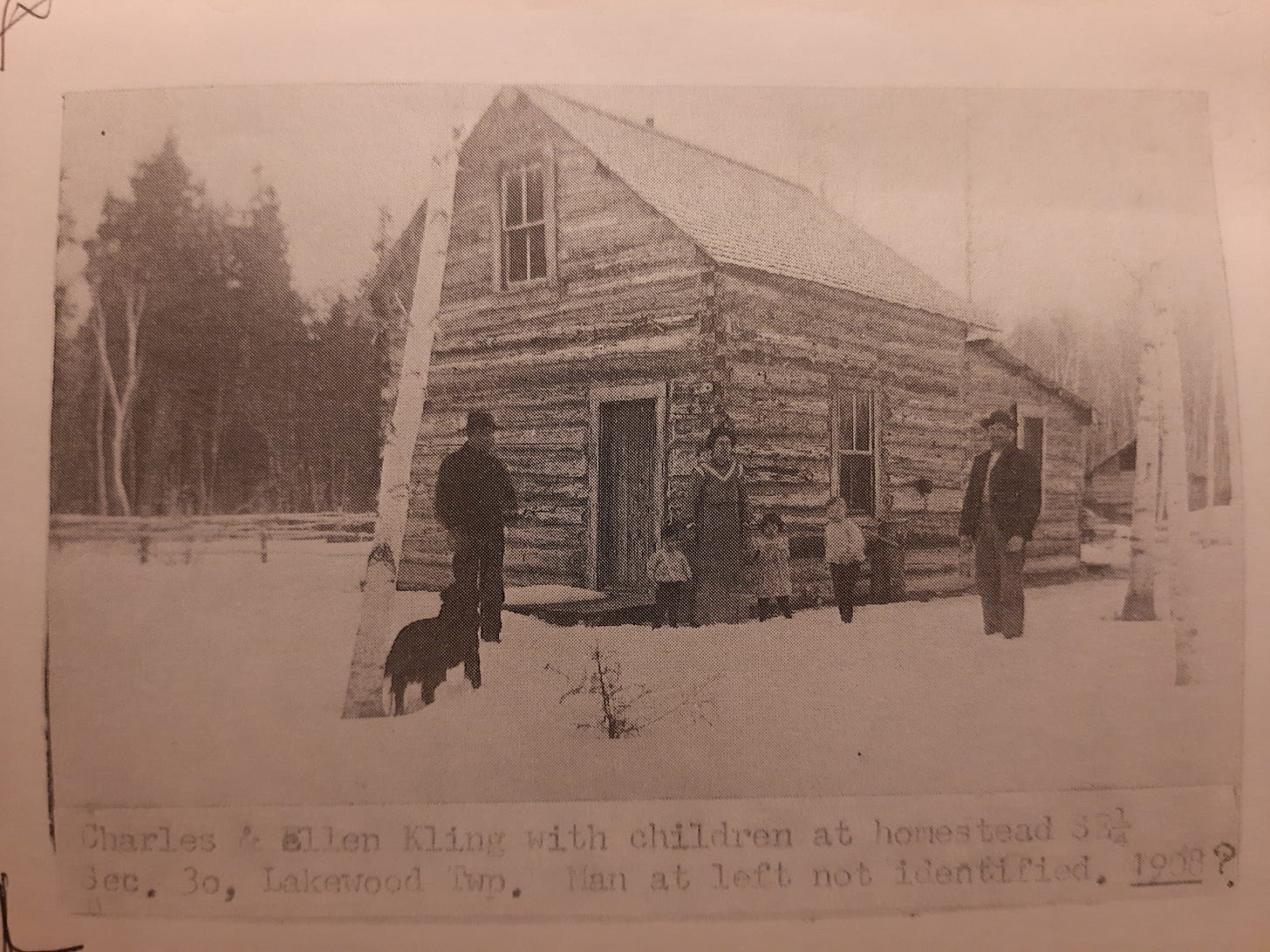

[Charlie Kling, foreground.]

I knew my great-grandparents had felled logs to build a home and barn, and they used oxen to plow the ground for flax and wheat. I went looking for old photographs I remembered seeing in Lest We Forget. When I opened to the first page, the epigraph jumped out at me.

Sometimes, that which we know, is found to be, quite simply, not so.

Charlie Kling had arrived from Sweden and worked for a company that made wooden boxes and shipping crates at Marine on St. Croix, which is about 40 miles north of Minneapolis. In 1903, he had moved his wife, Ellen, and her mother and brother north 350 miles to stake a claim next to the farm of his wife’s sister and her husband. I didn’t think of my great-grandfather as part of the timber industry. I’d thought of him as a family farmer.

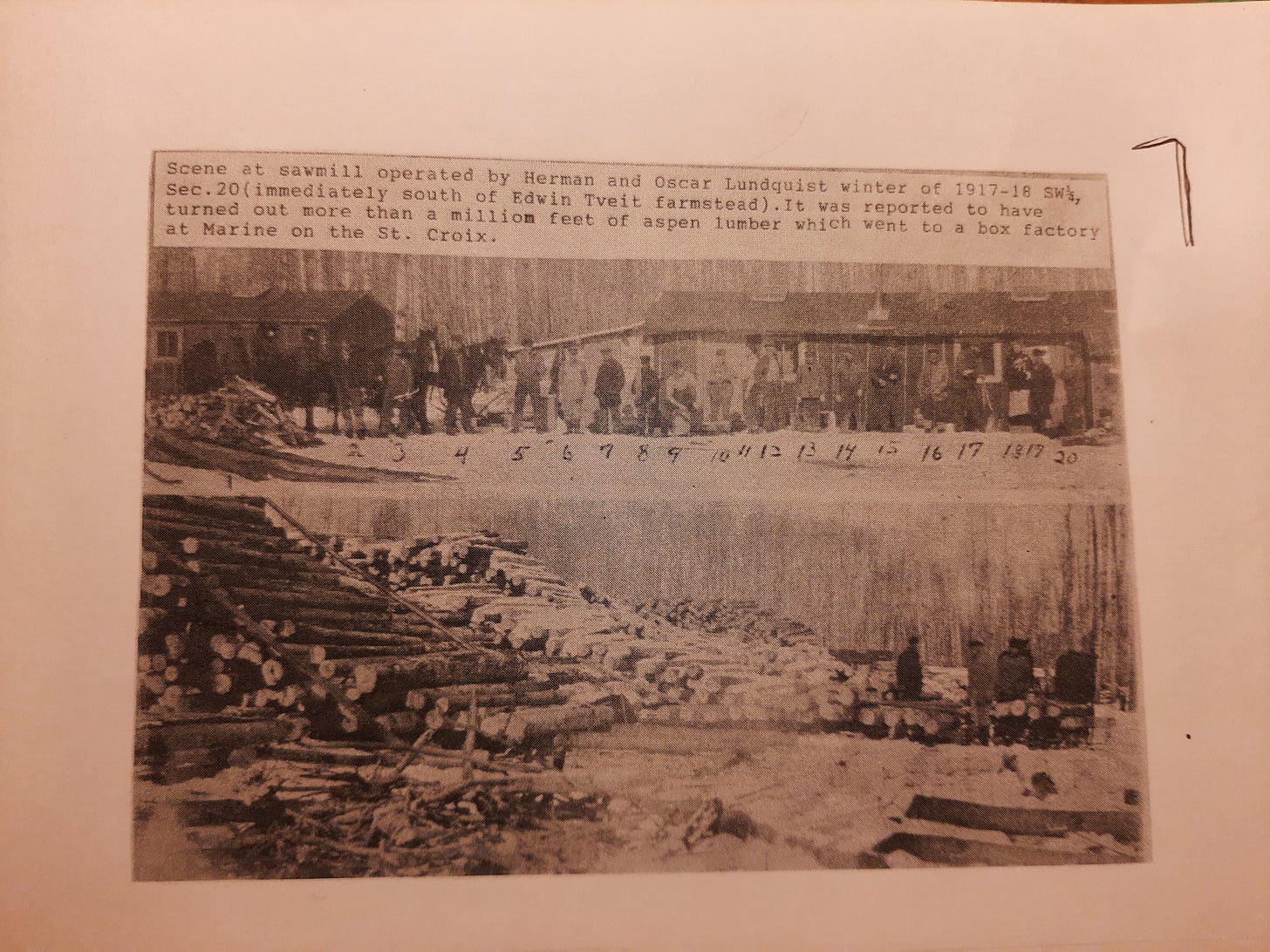

But when I read the caption to the two photographs below more closely, it dawned on me he worked for more than a decade clearing timber on the land. The photo shows two scenes at a sawmill operated in the winter of 1917-1918 less than a quarter mile from my great-grandparents’ farm. This sawmill “was reported to have turned out more than a million feet of lumber which went to a box factory at Marine on the St. Croix.”

[Photographs taken of pages in Lest We Forget, T. E. Helmstetter, 2005.]

While my great-grandfather wasn’t a timber baron, he worked in the industry. An industry which had pressured the US government to sell off reservation lands. An industry which clear cut forests. An industry which eventually left behind a century of toxic waste in the waterways.

While my great-grandfather didn’t kill any Indians or force their removal, Charlie Kling staked his homestead claim on a portion of Red Lake Reservation ceded under the “Dead Indian Act” of 1902. This updated version of the 1887 General Allotment Act was called the “Dead Indian Act” because it made it legal for the heirs of an allottee to sell the allotment. It also permitted Indians, including Kakaygeesick and his brothers, to retain lands on which they lived instead of moving them to the diminished Red Lake Reservation. The federal government issued them allotment papers dated 1905 designating the boundaries of their property.

While I had learned the history of westward expansion to be a violent one filled with wars against Indians and broken treaties, there is a quieter side to that history of cultural domination. One cloaked under the guise of government bureaucracy and law which used reservations and allotments to extract control of the land and resources. One which meant my great-grandfather could peaceably stake his claim.

I don’t like to think the long history of government attempts to “eradicate the Indian problem” were made on Charlie Kling’s behalf and to his benefit. But they were. I can’t ignore this if I am interested in knowing the truth about my past.

More powerful and telling research Jill. Thank you for sharing your journey into this much facetted history with us.

Thank you for your truth telling family history Jill.