Did Naymaypoke sell his land so Indian children could attend school?

or did the Warroad school district purchase land to build a bigger school for white children?

Ever since I was a kid I’d heard the story that Chief Naymaypoke had given his land to build a new school in Warroad which all children could attend, including Indian children.

I confess, I wish I could believe that.

How much of this local legend can I verify? I have been searching through the digital photographs my sister, Barb, took of school district records, which she sent me from the Minnesota History Center in St. Paul.

Last week I addressed the complicated question of how the Warroad School District acquired Naymaypoke’s land.

Let me tell you what happened after the school district paid him $150 on March 23, 1905.

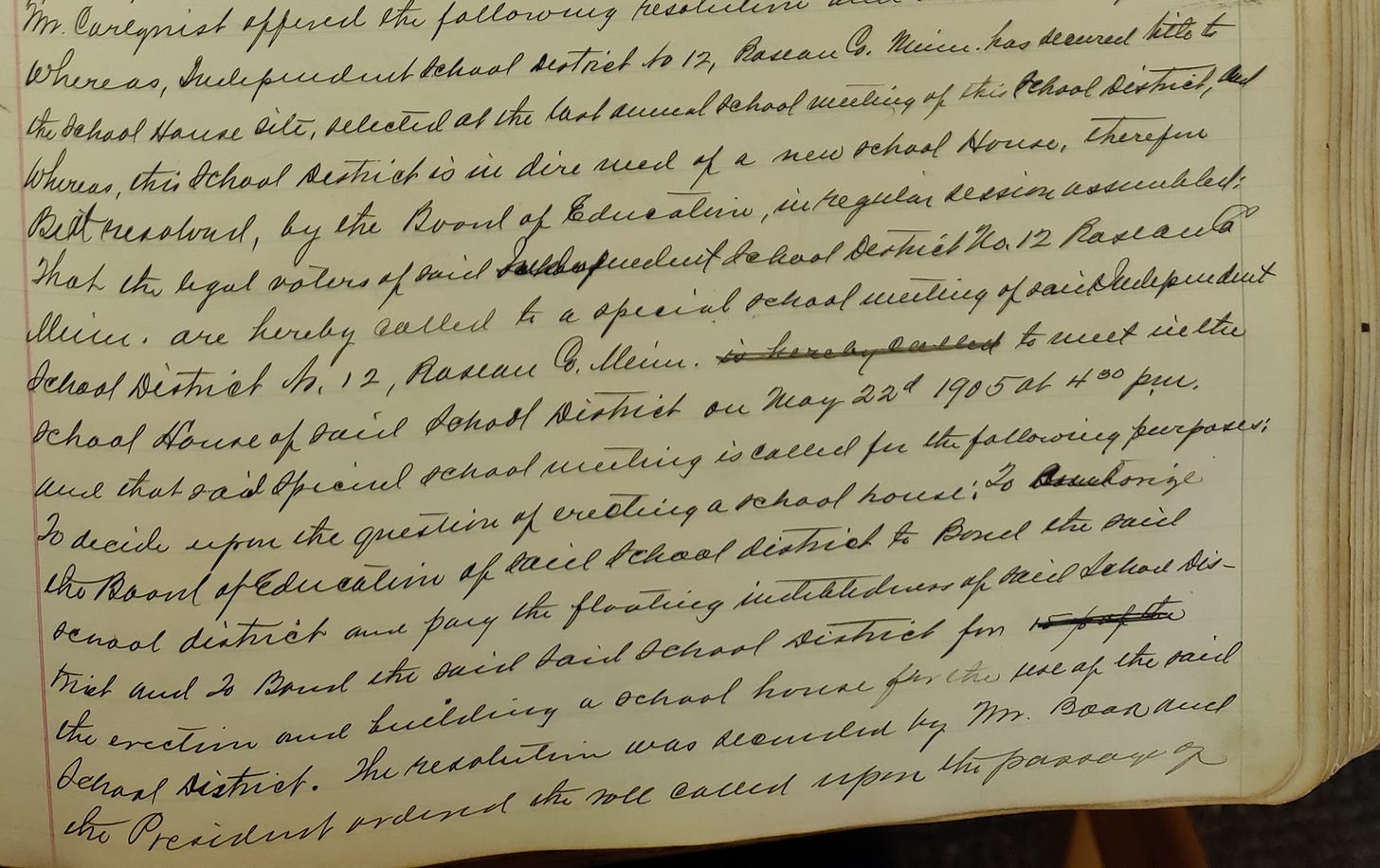

The board members met on May 9, 1905, to propose building a new schoolhouse. “Whereas, Independent School District 12, Roseau Co. Minn. has secured title to the School House site, selected at the last annual school meeting of this school district, and whereas, this School District is in dire need of a new schoolhouse, therefore…”

This photograph gives you some sense of why this research takes me so much time. Deciphering the cursive is challenging.

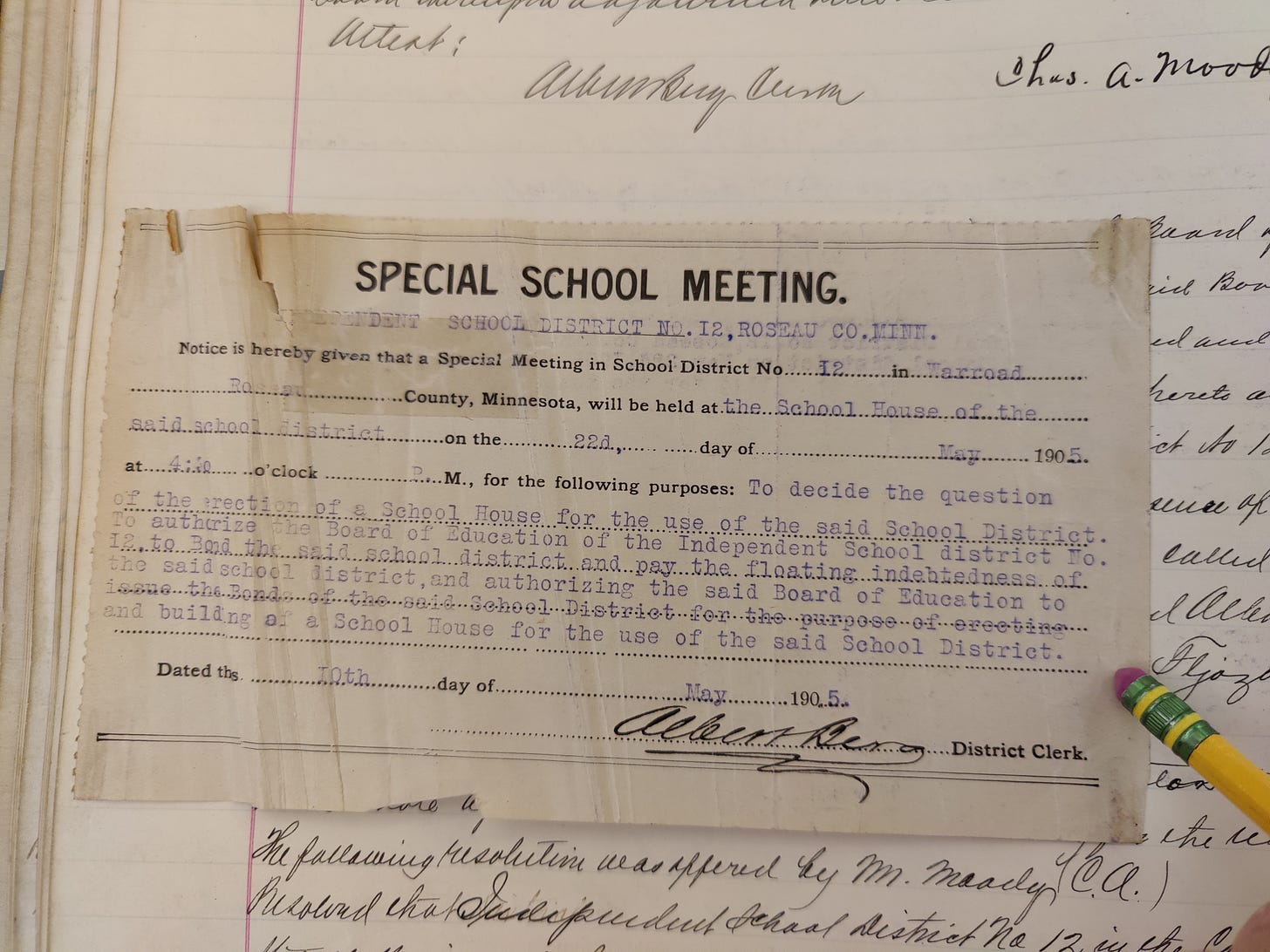

The school board scheduled a public meeting for May 22 to let voters decide on the question of school bonds for a new schoolhouse.

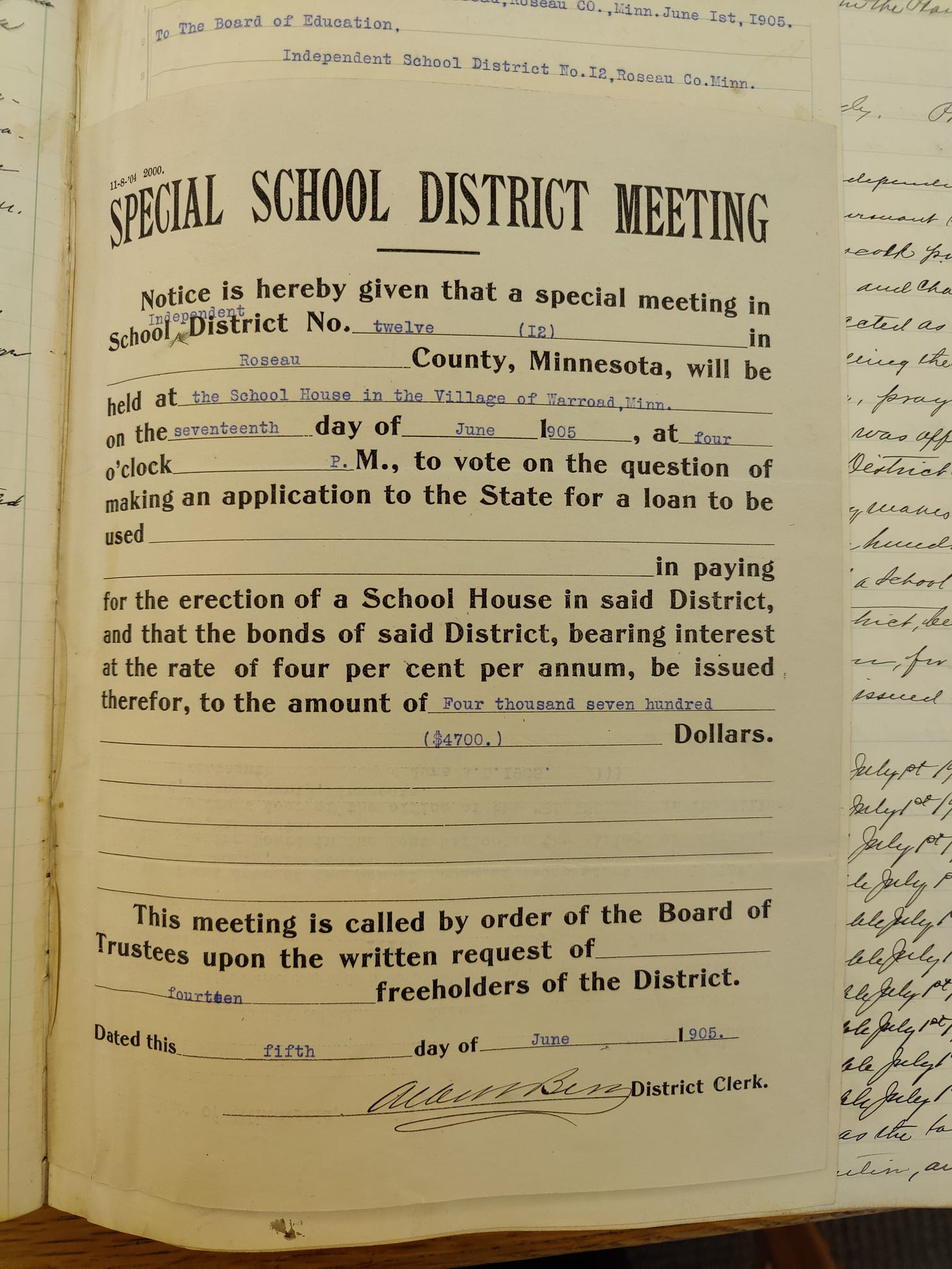

A petition resulted from that meeting; signed and dated June 1, 1905. “The undersigned, freeholders and legal voters of Independent School District Number Twelve, Roseau County, Minnesota, hereby petition you to call a special meeting of said District to vote on the issue of bonds of the said School District in the sum of $4,700.00 for building a School House.”

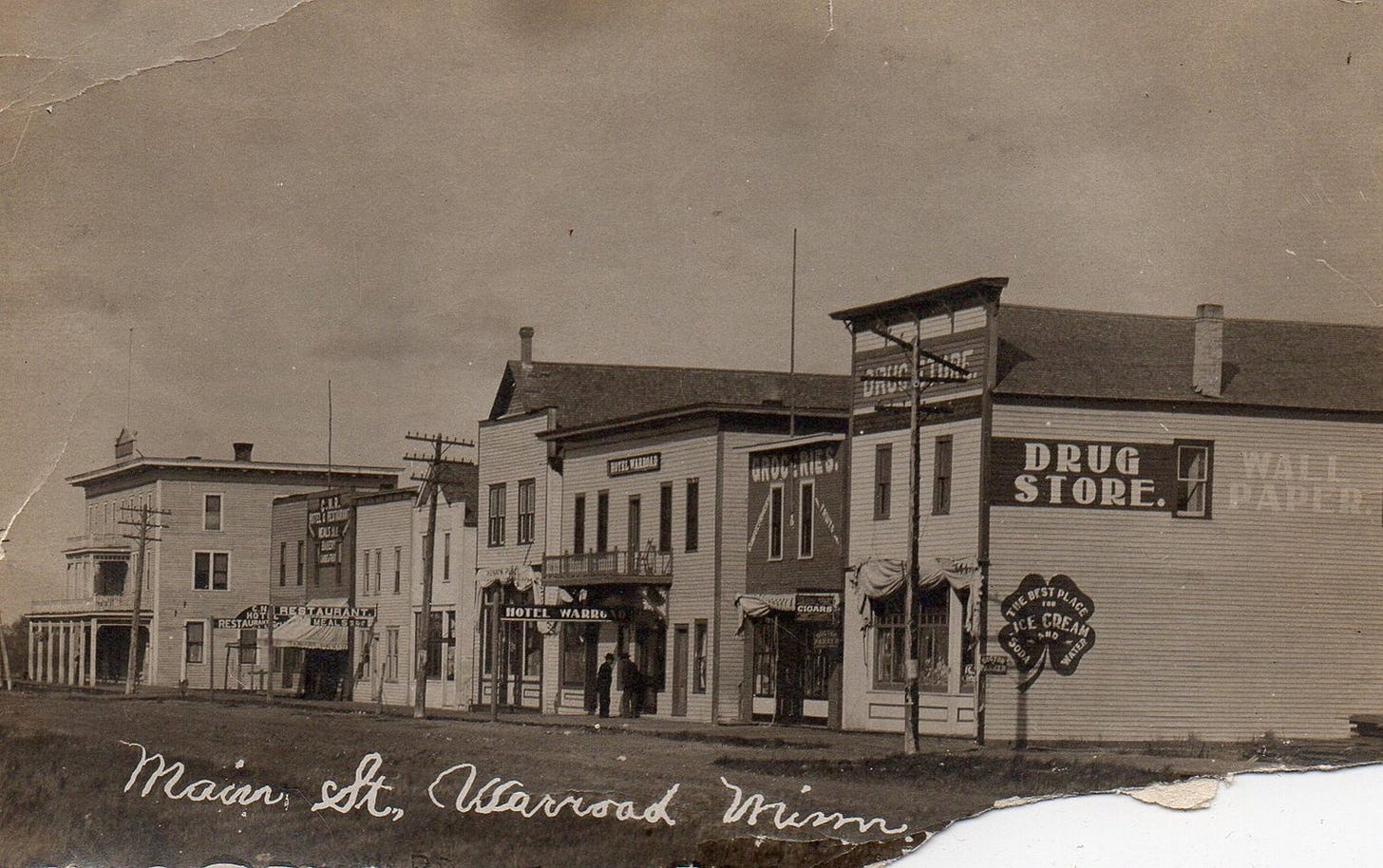

These are the signatures of fourteen white men. “Freeholders” seems to me rather arcane language forty years after the Civil War. Yet, it had only been 1902 when Minnesota diminished Red Lake Reservation and opened the Warroad area to homesteaders. By 1905, all the homestead land had been claimed. In this context, “freeholders” refers to those who are eligible to vote on public school matters, including white residents from Canada or Europe.

The name of Chas. A. Moody is familiar to many from this area. There is a street in Warroad named after him. Mr. Moody staked the first homestead claim in Warroad, served as president of the school board in 1904 and 1905, and became mayor in 1910.

Two months after they signed the check for title to the property, the school board met on June 1, 1905, to schedule a special school meeting for June 17 and the public notice appeared in the Warroad Plaindealer. The stated purpose: to vote on whether to pursue a loan from the State of Minnesota, financed with school bonds, to erect a new schoolhouse.

Mr. Moody moderated the special school meeting on June 17, 1905, and the vote passed.

Perhaps the urgency to act quickly after acquiring title to Naymaypoke’s land is explained by the size of the burgeoning student body. In their application for state aid of $250 to pay their two school teachers for nine months, the clerk completed the official form which required information about the existing schoolhouse of log construction.

Room A on the first floor was 36 feet by 28 feet and Room B on the second floor was 30 feet by 20 feet; total square footage of 1,608.

Room A had 50 students and Room B had 55 students. Two teachers for 105 students. “Dire need” is no exaggeration.

The financing secured, the school board proceeded with the construction of a new schoolhouse which opened in 1907.

The school census records from 1904-1920 are incomplete, but I can find no record so far of Indian students enrolled in the Warroad school before 1920. I have found clear evidence from the 1920s forward, but none from the first years of public education in Warroad. I’ll share more about what the records do tell about student enrollment next week.

But here’s what I know to be true in this story that I’ve heard since I was a kid.

The Warroad school district acquired the land from Naymaypoke.

The school district built a new schoolhouse.

The school (eventually) enrolled Indian students.

Over time, these story elements have endured because they are true. They are based on facts documented by public records. But the legend as I learned it had erased facts and whitewashed what had happened.

The story I grew up with made me feel good. Looking back now as the great-granddaughter of Swedish immigrant homesteaders, I wonder if that might have been the point.

The nobility of an Indian who gave land for a public schoolhouse to send his grandchildren to be assimilated — I recognize this as a common trope in American pioneer folklore. The mythology of the Noble Savage, the Vanishing Indian, evokes the nostalgic feelings I have for a better version of the past than what really happened.

I can’t forget that after military attempts to exterminate Indians proved unsuccessful, the federal government pursued assimilation policies. The legend in Warroad doesn’t represent Indians as mortal enemies in a fight for land. Instead, the story portrays Naymaypoke teaching Indian children to adopt white settlers ways.

This is a story about assimilation. It’s a story that made me feel good without any reason to question whether it was true.

Thank you Jill for this detailed history and reexamination of what we’ve been told. Can you say a bit more about what it means that “Minnesota diminished Red Lake Reservation?” By how much?

I'm hooked! I look forward to reading more about what you uncover and what really happened. And if you cannot find the exact historical documents, there may be enough context clues and personal knowledge to draw pretty accurate inferences