Let there be lefse

in memory of Mom

“If you don’t eat up all those mashed potatoes, Gramma is going to make me a mashed potato sandwich for lunch tomorrow,” Grampa Swenson used to tell us grandkids at the table on Sundays.

Gramma carried out his threat one Monday and sent him off to work with a glob of cold mashed potatoes between two buttered slices of white bread. She never heard him say it again.

And that’s probably because there weren’t any leftovers.

Swenson grandkids aspired to membership in the Clean Plate Club. Some of us were card-carrying members. At home, Dad would pull a business card he’d picked up during the week out of his wallet and hand it to us when we finished everything we’d been served for supper. Of course, this was before we could read.

Today I understand my parents and grandparents intended to instill in me a sense of how privileged I was. There were starving children in Korea, I was told repeatedly.

Canned peas did not feel like privilege, and neither did mashed potatoes. But mashed potatoes did taste like love.

I was a good girl who cleaned her plate. One of those things I was told Santa would check to find out if I were naughty or nice.

Potato pancakes, potato salad, twice-baked, au gratin, fried, roasted, soup, hotdishes covered in tater tots – these are the recipes I learned to cook in the kitchen of my mother and grandmothers.

Sitting in the chair next to the window, I watched Granmma Swenson make potato sausage. She tightened the vise of the meat grinder on the edge of the table in her tiny, cramped kitchen. She placed a big bowl under the contraption with a crank for a handle. Grandma tossed chunks of raw veal and pork into the funnel on top. She wiped her bloody right hand on her apron and turned the handle on the crank. The meat came out below like a Play-Doh squeeze machine – a clump of threads landing in the bowl.

She added her own blend of mild seasonings. The tiny tins of McCormick spices lined the back of the narrow countertop behind me.

“Hand me the Allspice,” Grandma said.

I turned to look in confusion. All the spices?

“Short tin. Capital A.”

I found it.

She pulled a colander of cooled chunks of boiled potatoes out of the sink and set it in the table next to the meat bowl. Then she took a potato and put it in the ricer, pressing it though the tiny holes; adding it to the pork and veal.

She washed my hands with soap and water. The porcelain sink and drain board had a footstool underneath for me to stand on. She turned the faucet on and lathered her hands and enveloped hers in mine, then toweled them off together.

Grandma showed me how to mix the potatoes into the meat with my hands. She kept ricing potatoes into the bowl and I kept squishing my fingers to mix it up. When she finished, her hands joined with mine in mashing it all together.

She made me watch as she squeezed the mixture into the casing. A foot-long sausage formed a ring and then she tied it off with a white cord.

Swedish sausage was always served at Christmas.

And so was lefse.

My mother mastered the art of lefse.

Mom made it for family and she also made lefse with the church ladies at Afton Memorial Lutheran preparing for the Advent fellowship hours between services on Sunday mornings. Thousands and thousands of lefse rounds dry fried in white flour over the decades. She had the right recipe and the right technique.

Over the years, my attempts to make lefse always tasted like shoe leather. I gave up, relying on Mom to send me annual care packages when I lived out of state. Lefse from Mom tasted like love.

My younger sister Barb took lessons from her. Barb came for a visit this week and brought Mom’s lefse griddle.

“Who taught Mom to make lefse?” I asked

Neither of our grandmothers made lefse by hand. Mom could have bought it like she did the Swedish sausage. But she didn’t.

In December she made lefse from scratch. We hovered around her in the kitchen waiting for the next one to come off the griddle to smother it in butter and eat it while still warm. Entire evenings she’d make lefse hoping to hide some away so she’d have enough to serve at Christmas.

“Do you remember when she tried to make it with instant potatoes?” Barb laughed.

I did. She didn’t try doing that again. Tasted like paper, or a communion wafer. Blah.

Barb said Mom took a class once. But mostly, it came with decades of practice.

Lefse is basically mashed potatoes, with cream and butter, and a lot of white flour. The mixed ingredients create a dough that is rolled out thinner than pie crust into rounds.

The lefse round is moved onto a dry flat griddle using a thin wooden long spatula. Here’s a video on how to use the lefse turning stick.

Barb brought Mom’s stick to use. I thought of it as her magic wand the way she maneuvered the paper-thin dough off the counter and onto the griddle.

Once the lefse was on the griddle, Barb watched it turn almost beige. She used the stick again to flip the lefse over and dry fry the other side.

Lefse is served by spreading butter on one side and rolling it up like a log. Don’t make the Norwegian mistake of sprinkling cinnamon and sugar on it. Ew. Swedes don’t do that.

Lefse doesn’t really make me feel Swedish, but it does make me feel loved by family. Barb’s lefse using Mom’s recipe never tasted more like love.

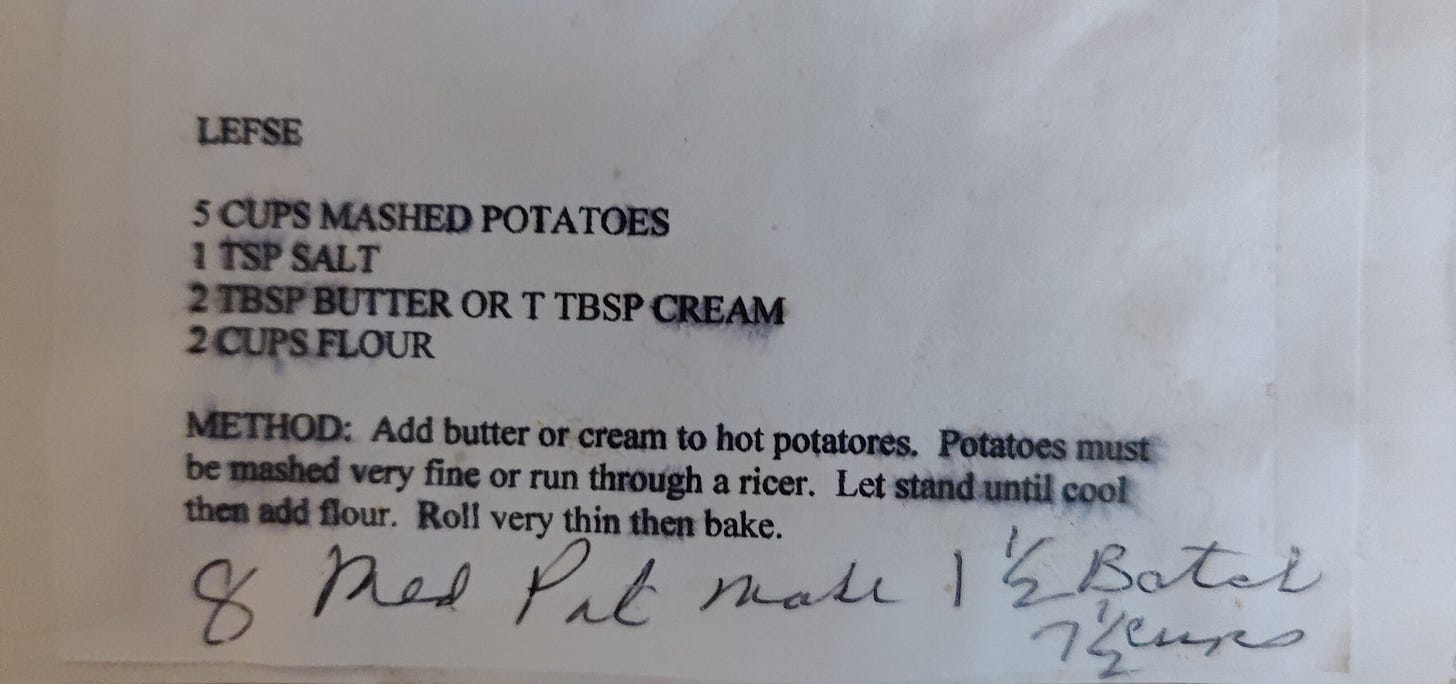

Mom’s Lefse recipe

Ingredients:

5 cups of mashed potatoes (mashed, not whipped; not instant either)

2 Tablespoons of butter or sweet cream

2 cups of white flour

Instructions:

Prepare a large surface for rolling out the dough with white flour. Dust the surface of the rolling pin and the flat surface with flour.

Pre-heat an electric frying pan or lefse griddle to 375-400 degrees.

Add 2 Tablespoons butter or sweet cream and 2 cups of flour to the mashed potatoes and mix until all the flour is absorbed. If it has not yet formed itself into a ball, then add more flour one tablespoon at a time and stir it in until it has the consistency of pie crust dough.

Pinch off a piece of the dough and roll out into a round much as you would a pie crust. Use flour to keep the lefse from sticking to the rolling pin and surface. The flatbread should be 1/8 inch thick or thinner.

Transfer the lefse round to the skillet and watch carefully so it doesn’t burn. The lefse will begin to brown slightly and it may begin to swell up with steam before it exhausts itself. When you begin to smell burnt flour, turn it over. You’ll smell burnt potato — different from burnt flour — if you wait too long. The lefse should be golden brown in round blobs and the rest still floury white.

Remove the lefse round when both sides are slightly browned. Once you remove a round, let it cool on a rack.

[Tee hee. Like that’s gonna happen! Best served immediately.]

You are fortunate to have antique photos to go with your sweet, homespun story. Yes, food = love!

potatoes, potatoes, potatoes! You know I gotta try this recipe! This was a delightful post. a great read. of love and tradition. And I really enjoyed all the photos you included. It's so great you have so many! I only have one potato tradition to offer up and I doubt it is related to my German and Irish heritages: fried oyster candy. Made with mashed potatoes. They are totally addicting. "Bolby's" (sp?) candy store in Appleton used to make and sell them. As a child, I would walk downtown every Christmas holiday to purchase some. For a while, they sold some in grocery stores, but they are long gone. I had an original recipe from a friend's great grandmother in Appleton, but had lost it over the years. After the internet started up, for years I searched for it again and finally found it in a local quilting group about 20 years ago. A 90 year old quilter was active in the group and shared the recipe. :-)