Mr. Monkman and the Riel Rebellion

Métis man exiled from Canada among first homesteaders in Warroad

This summer when I decided to take a much deeper dive into the local archives — most of which have never been digitized — I desperately wanted to find answers to lingering questions about how at the turn of the twentieth century the old Ojibway village of Kah-bay-kah-nong became the new city of Warroad, Minnesota.

My research trip to Roseau County in June yielded a lot of new discoveries about the early settlers of Warroad. Mr. Charles A. Moody was not the only pioneer who encroached on unceded Red Lake Indian land and earned a living from settlers moving to Warroad.

Another significant character in this story is Albert Monkman, a name I first ran across next to Moody’s while researching the start of Roseau County.

In January of 1896, Mr. Charles A. Moody became the first County Auditor and I noticed Mr. Albert P.J. Monkman became its first County Coroner.

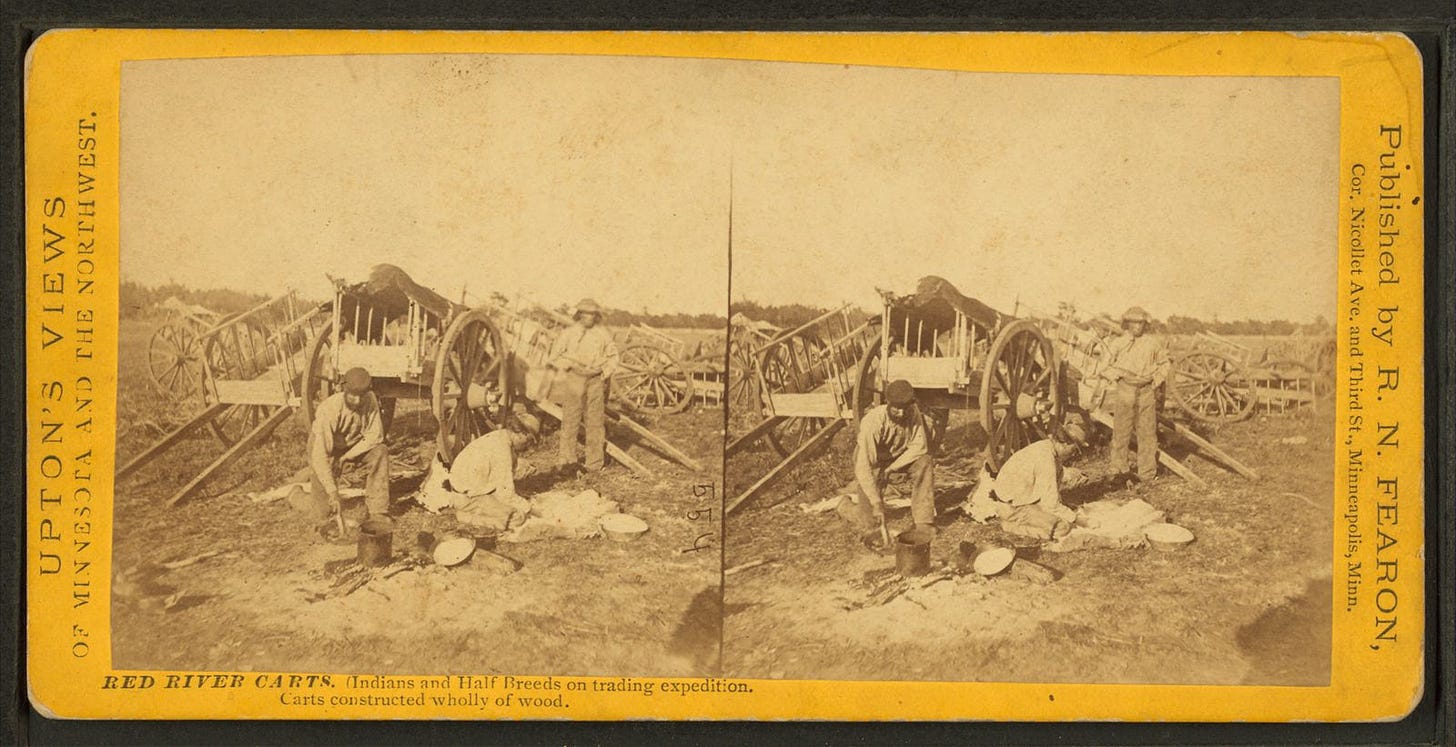

Monkman had first come to the village of Roseau a decade earlier. He had worked for the Hudson Bay Company since 1867 as a “carter.” A carter drove Red River Valley ox-carts between St. Paul and Winnipeg.

It was in a collection of stereoscopic views held by the New York City Public Library where I found an image of these ox-carts from near Roseau.

On October 30, 1893, Monkman purchased riverfront property in Roseau. Like Moody, his story about what brought him to Warroad widened my view of encroachment along the Canadian border.

It also made me aware of how little I know about Canadian history.

While the United States started with British colonies leading a revolution against the King of England, Canada began as a confederation of colonies loyal to the Crown. The country didn’t exist until 1867.

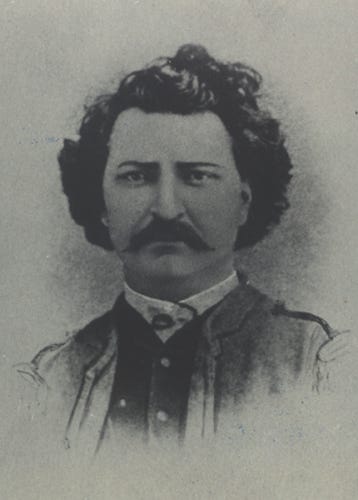

Canada didn’t have a revolution, but there was a rebellion — the Riel Rebellion — that nearly split apart the new Dominion of Canada. And like the Civil War in the United States, which had recently ended, race and civil rights were at the heart of the conflict.

I didn’t know much about the Métis people and even less about the Riel Rebellion when I found Mr. Monkman had been among the first to file a homestead claim in the Warroad area. I have spent several weeks doing some remedial reading on the subject. I even watched a 1979 Canadian made-for-TV movie titled Riel starring Christopher Plummer as Canada’s first Prime Minister, Sir John Alexander Macdonald. William Shattner plays a cameo role as the barker in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

Like Kevin Costner’s Horizon (now streaming on MAX), this film personifies the complicated history of land encroachment with a diverse cast of characters. Louis Riel is the heroic figure in Riel, the movie. In case you’re interested in spending two-and-a-half hours learning more about Louis Riel and the history of the Métis resistance movement, here’s a free version available on YouTube.

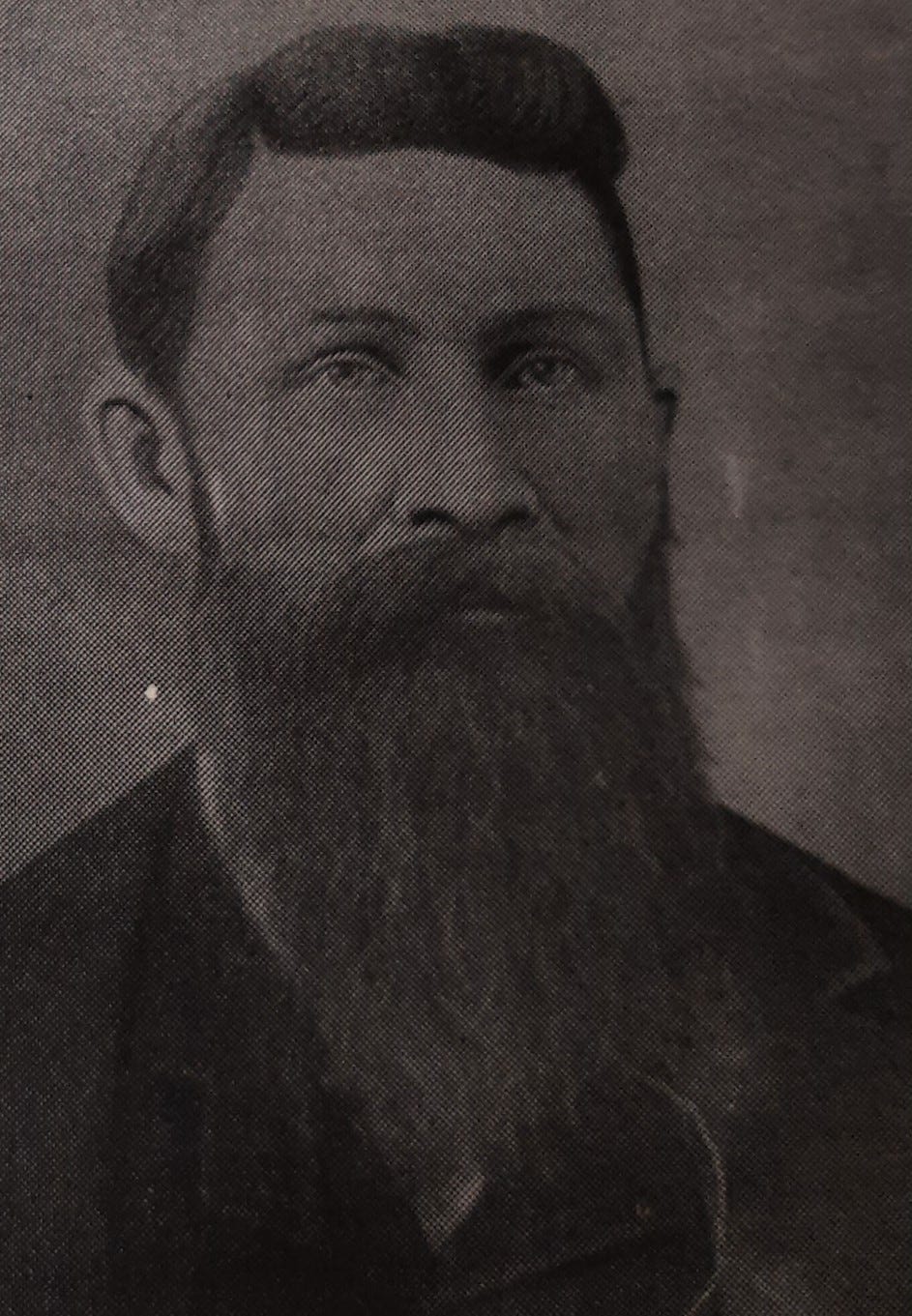

Albert Monkman is not a main character in the film, but in real life he served as second in command to Louis Riel in the Battle of Batoche in May of 1885. Monkman surrendered, pled guilty to treason, and was sentenced to seven years imprisonment in August 1885. After serving 11 months of his sentence, Monkman received a pardon and slipped quietly across the border.

Who was this Monkman and what had brought about this armed resistance to white settlers encroaching on lands in Canada?

Monkman had been born on March 1, 1854, to Joseph and Isabella Monkman. They baptised him on March 27, 1854, at St. Andrews, in the Anglican Church of Canada, in the Diocese of Rupert’s land.

Prince Rupert received a charter in 1670 from King Charles II to create the Hudson Bay Trading. The charter gave a monopoly on trading rights over all the territories whose rivers drained into the Hudson Bay. This included the lands along the Roseau River.

The first Monkman to work for the Hudson Bay Company came in the 1700s from the Orkney Islands of Scotland to the York Factory on Hudson Bay. Numerous descendants of this Scottish-Métis family had associations with the Hudson Bay Company, incuding his grandfather, James, who had married a Cree woman known only as Mary.

When Albert Monkman turned 21, he married Mary Ann Morwick, listed as a spinster at the age of 18, on March 10, 1875, in the same St. Andrews church where he had been baptised. He stood taller than six feet, had black hair, a dark complexion and gray eyes.

What I had failed to appreciate about Canadian history is how closely at the turn of the twentieth century it paralleled the US in a race to eradicate Indians in westward expansion — from sea to shining sea — propelled by politicians motivated by land acquisition and tying the nation together with train tracks. Encroachment happened on both sides of the border as white settlers eagerly claimed property on Indian lands.

Before the Northwest Territories had been ceded by treaty, Prime Minister Macdonald authorized incursions into Indian lands to begin construction of the railway. When a construction crew accompanied by Superintendent Crozier of the North West Mounted Police began to lay railroad ties through the middle of their plowed fields near Duck Lake in 1869, it led to the Red River Resistance and Louis Riel declared himself governor of a provisional government of the Métis Nation.

Prime Minister Macdonald made a few concessions to Riel and his growing movement. The Manitoba Act of 1870 admitted Manitoba as the fifth province of Canada. Louis Riel was elected to Parliament, more than once, but he was not admitted to its chambers. The government enticed Métis residents to permit access to their homelands in exchange for scrip. Métis scrip was like a coupon to be redeemed for a 160-acre parcel of land or $160 in cash. Prime Minister Macdonald intended to construct a transconstinental railroad. He encouraged immigrants to settle out west and he needed the Métis out of his way.

The same year he married, Monkman submitted a scrip application for land at Duck Lake.

“I claim to be entitled to particpate in the allotment and distribution of the 1.4 million acres of land set apart for Half-breed children, pursuant to the Statute in that behalf….” Monkman signed this affidavit on July 23, 1875.

A sworn statement from the commissioner that Monkman had read the document and “seemed to understand the English language perfectly well” was included with his sworn oath that Monkman signed in his presence. This seemed odd until I realized “Half-breeds” were likely assumed to be illiterate. While the term today is considered a racial slur, in Canada this designation became codified into law.

Louis Riel left Parliament in 1875 and by 1877 had been sent to an insane asylum for his radical ideas. He was released upon his promise to seek exile in the United States. He crossed over into Minnesota and moved to Montana where he married. There he found the Métis all along the Canadian border similarly dispossessed of their homelands. The Métis asked him to return to Canada to fight for them in 1885.

Monkman organized the militia near Duck Lake under Riel’s leadership. His men first skirmished with the Canadian Mounties on March 26, 1885. The Mounties suffered significant casualties.

The Battle of Duck Lake proved an embarrassing defeat for the Crown and a victory for Louis Riel, who had demanded in writing the rights of the Métis — to land and respect and human dignity. Riel, who had attended Catholic seminary and worked as a law clerk, used his pen like a sword.

Prime Minister Macdonald considered Riel a problem to be eliminated and went to war against the Métis. Troops were sent to protect white settlers from being forced off land they’d claimed and improved with the Prime Minister’s encouragement. The final battle at Batoche lasted three days in May of 1885 before Louis Riel and his rebels surrended. They were charged with treason.

Monkman pled guilty and was sentenced to seven years of imprisonment on August 13, 1885, according to the Regina Leader Post.

Louis Riel was executed by public hanging on November 16, 1885.

In 1886, Monkman quietly established a new life for himself south of the border and he celebrated Christmas of 1889 when his wife and children moved to be near him in Roseau. He continued to work as a carter in the Red River Valley. On October 30, 1893, he purchased a $100 parcel of land on the Roseau River near the center of the community. When Roseau County officially organized its charter on the last day of 1895, Monkman and Moody assumed their new roles as County Coroner and County Auditor.

It wasn’t until May of 1897 when Monkman officially became a U.S. citizen. He and his wife Mary Ann had three sons — Thomas, Lawrence Martin, and Louis Riel — and a daughter, Alice. During that first term of school in Warroad, Louis and Lawrence were in attendance in the schoolhouse on Naymaypoke’s land.

Monkman established a saw mill halfway between Warroad and Roseau at Hay Creek in November of 1897. As spring arrived in 1898, “Capt. Monkman” placed a paid notice in the Roseau County Times annoucing he had a “large mountain of sawdust and slabs free to parties who will take them away” as they could be “used to good advantage in repairs to the Warroad road.”

The transport from Roseau to Warroad of new families and their household goods kept Monkman’s business brisk. His home at Hay Creek also operated as a “Halfway House.” It was about halfway between Roseau and Warroad, where Albert Monkman and his wife Mary Ann offered overnight accommodations to travelers moving to unceded Indian territory.

In August of 1898, The Roseau County Times reported “Capt. A.P.J. Monkman” announced he would hereafter identify himself with the Republican Party. The upcoming gubernatorial race matched Republican William Henry Eustis against John Lind, a candidate who earned the endorsement of the Democratic Party and the People’s Party. The People’s Party had been formed in 1892 during the agrarian movement and represented the interests of farmers and working people. Monkman had renounced his allegiance and resigned his position as the Secretary of the People’s Party County Committee, the Times reported.

I can’t help think Mr. Moody and his new friend in Warroad, Republican Secretary of State Albert Berg, might have had something to do with Monkman switching parties. But I could find no evidence.

“Mr. Monkman is not alone in his change of politics in this county,” The Roseau County Times reported in the same article. “There are at least 100 populists who will vote the republican ticket this fall and the democrats almost to a man in the county will cast their votes for the Republican nominees.”

Republican gubernatorial candidate Eustis, however, lost the race by a wide margin to John Lind that November.

In mid-December 1899, Monkman rented his Hay Creek saw mill to O. L. Haugan who agreed to keep the Halfway House in operation. Monkman’s transport business had grown and included mail delivery between Roseau and Warroad. He moved his family into Warroad.

On April 20, 1900, The Roseau County Times reported the court awarded a divorce to A.P.J. Monkman from his wife Mary Ann. In September, The Warroad Plaindealer reported “Mrs. Monkman is running a laundry…down by the Chief [Naymayoke]’s house.” It wasn’t long before Albert Monkman married Flora Flick.

When the Canadian Northern Railway opened the depot in Warroad in February 1901, passenger trains brought settlers. Once they arrived, they needed transport to their final destination. According to The Warroad Plaindealer, Monkman “bought half interest” in the Roseau-to-Warroad stage coach line in April of 1901.

The lands around Lake of the Woods near Warroad officially opened for homestead claims on February 16, 1903.

Monkman returned from Crookston on February 27, 1903, where he had filed a homestead claim at the Land Patent Office on his squatters claim in the Hay Creek district. The newspaper reported Monkman beat his neighbor Pieper who had filed a competing preemptive claim on part of the same land.

Monkman worked with Moody to bring telephone service to Roseau County in 1903. The phone company agreed to string a line from Thief River Falls, if Monkman could get people to furnish and lay out the poles. Monkman made it happen. The first telephone was installed with a line between Mr. Moody’s house and the train depot.

In March of 1904, Monkman’s mother died in Selkirk, Manitoba. He had not dared to return for her funeral, for fear of political persecution and possible prosecution. Bereft, Monkman yearned to return home.

It wasn’t until 1907, when he decided enough time had passed that Monkman sold all his interests in Roseau County and took the train to Winnipeg. There he was seized, arrested, and charged again with treason.

In consideration of his previous prison time and recognition of his pardon, the court released him after a short detention. Monkman took a job with the provincial government of Manitoba as “Farm Instructor” to Indians, advocating they adopt agricultural methods to replace the lost buffalo and end of the fur trade.

He didn’t last long there. He moved to Alberta and became postmaster in a small place later named Monkman. He died there on March 9, 1911, at the age of 56.

Monkman is still a familiar surname in the Warroad area. Albert’s son Louis Monkman became a well known commercial fisherman on Lake of the Woods. Dennis Edgar Monkman, a WWII veteran, ham radio operator, and grandson of Albert Monkman, spent his retirement years back in the Warroad area and died at the age of 86 in September 2023.

Fun fact: Wab Kinew, the current premier of Manitoba, is a descendant of Louis Riel and married to Dr. Lisa Monkman, a family physician.

Newsflash: Milkweed Editions released a new memoir this past week by

(who writes An Irritable Métis here on Substack) titled Becoming Little Shell: A Landless Indian’s Journey Home. I did not read it before writing about Mr. Monkman, but I look forward to soon.

Wow! Just wow! This is an extraordinary piece! You're putting faces on the people who implemented the encroachment. It was not just an abstract process. These are real people. This piece stands as a tribute to your substantial research work. It may be longer than your usual post, but the research warrants sharing.

I've always wondered what happen to the rest of the rebels after Riel was "martyred".

All of this writing keeps bringing me to deeper and for me really troubling questions. Of course the reappearing words like encroachment and "half-breed" cause inside of me these inquiries. I want to climb inside the head and hearts of people who made certain decisions, and of course that is impossible. For me, manifest destiny is a horrible worldview. I recognize that many of the encroachers identified as Christians who were able to look at indigenous people and see them as sub-human and somehow justified their taking of others' lands as acceptable and heroic behavior. I will forever be amazed by my contemporaries who simply say they personally were not around at the time these atrocious acts were committed and therefore they bear no responsibility for all that unraveled. As if they want me to believe, they wouldn't have themselves participated in the violence, theft, and sustained abuse.