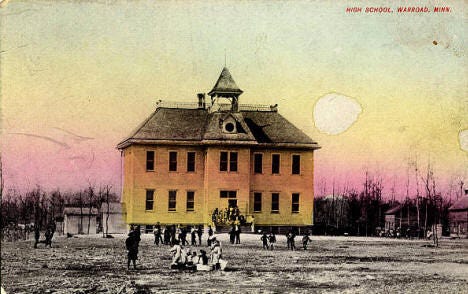

In 1928, John Lightning was the first Ojibway student to graduate from Warroad High School, nearly a quarter of a century after his great-uncle Naymaypoke had sold his land to the school district.

John Lightning was the youngest of three children born to Ethel and Tom Lightning.

In 1971, Grace Landin interviewed Tom (1876-1974) and Ethel (1888-1972). Grace taught in Warroad and conducted extensive interviews with descendants of Chief Ay Ash Wash. “A Study of Three Chippewa Families at Warroad, Minnesota, and Their Historical and Cultural Contributions,” is the master’s thesis she completed at Moorhead State College.

Tom Lightning told Grace that after Naymaypoke sold the land to the school district, he wanted to enroll his children, but he was told they were Canadians and they would be charged tuition (Landin, 1972:38).

Grace Landin also interviewed Tom and Ethel’s translator, their daughter Margaret, who was 10 years older than her brother John. Maggie Aas, as she had been known, answered Grace’s question about what school was like for her as a young girl.

Our parents took us to an Indian boarding school up in Shoal Lake, Ontario. I couldn't write my own name then. They didn't even try to teach us to learn to read or write. I guess we didn't know any different. They put all of us to work. We would go to a half day of school about three times a week. The rest of the time we would do housecleaning, sewing, cooking, and anything in the line of housework. The boys would do the outside work like cutting wood, caring for the cattle, and shoveling snow. There was a lot of work to be done outside for a big school. They had to do everything by hand (Landin, 1972:44).

Naymaypoke, Tom and Ethel Lightning, and others must have known about two other boarding schools in Minnesota, each about the same distance from Warroad as Shoal Lake. The one at White Earth Reservation, 120 miles southeast, had opened in 1871 and St. Mary’s Mission on Red Lake Reservation, 100 miles south, opened their boarding school in 1900.

Given the likelihood of his knowledge about boarding schools, Naymaypoke may have had good reason to negotiate terms with the Warroad school board in 1905 for his land. However, there are no school board records of such an agreement regarding the enrollment of Indian students in exchange for Naymaypoke’s land.

An internet search for the school Maggie attended in Shoal Lake led me immediately to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at the University of Manitoba.

I clicked on the link and learned it had been named the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School after a member of the Women’s Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church.

In 1899, leaders of the Ojibway band at Shoal Lake Reserve had petitioned the Presbyterian Church to build and staff a school for their children. They negotiated terms and signed a contractual agreement which stipulated “no heavy work for younger children, no baptism without consent, at least a half day of class time for older children, and provision for children to be absent for traditional events.”

This shows Ojibway resistance to assimilation. No baptism without consent and excused absences for ceremonies and cultural traditions — they had negotiated for spiritual sovereignty.

Despite the contract, school officials violated the negotiated terms from the very beginning. In 1994, the church made a public confession to providing poor living conditions and subjecting thousands of students over seven decades to physical, emotional and sexual abuse, and stripping them of their language and cultural identity. The Presbyterian Church of Canada has begun to implement the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to facilitate healing and foster more equitable relations between itself and Indigenous communities.

Many Canadians know Cecilia Jeffrey School from the story of Chanie Wenjack, a 12-year-old Ojibway boy who ran away from there in 1966. Found frozen to death along the railroad tracks, he had tried walking home almost 400 miles. His death exposed the inhumane treatment of Indian boarding school students across Canada and eventually led to government reform efforts. But the Cecelia Jeffrey School didn’t close until 1976.

In 1971, Tom Lightning described to Grace what he knew about conditions at Cecilia Jeffrey School a half century before Chanie Wenjack fled. Tom said Hans and Maggie returned after two years unable to read or write and had been put to work. “They were told never to say anything to anyone and not to talk to a white person who came to the school” (Tom Lightning, in Landin, 1972: 39).

Maggie was only seven and Hans was 12 when they set out for Shoal Lake in 1914, a decade after the school district proposed purchasing the four-acre parcel of land from their grandfather. From Warroad, Shoal Lake is about 120 miles by land or about 50 miles by water. They likely traveled there by canoe.

Maggie remembers attending school in Warroad after returning from Shoal Lake.

We had a late start, Hans and I, so I guess that's why we did not get much schooling. John had a better chance. He really loved school. I never liked school very much. The white children would tease me all the time. They would call me all kinds of names and I wasn't one to fight back. They would call me a "dirty Indian." Maybe they thought my skin was dirty when it was darker than theirs (Maggie Aas, in Landin, 1972:44).

Alvin (Ole) Swanson, a retired teacher who grew up in Warroad the same time as John Lightning, claimed in his pamphlet, Warroad Natives: The Chippewa (1975), that when four Indian boys entered first grade, they were told there were no desks for them and sent home. John’s father, Tom Lightning, had to offer to buy their desks before John, Louie Goodin, Albert and George Angus were finally admitted.

While the local legend conflated timelines and erased key facts, it is true that Naymaypoke’s grandchildren went to school in Warroad.

After graduating from Warroad High School, John Lightning (d. 1985) served in the US Navy for 29 years, including tours of duty in Korea and Vietnam.

Today's writing takes my breath away. I guess because I have been following all along and expected to begin to learn some of the truths of the conditions for students and their schools. You research awes me. I don't like learning about the suffering of children, but I am not surprised. No matter who causes these evil practices, they carry a deep wound. It is always especially troubling to recognize practices from formalized religions. P.S. I've just read Mary Roblyn's comment, and I feel the same about the story of Chanie.

Seeing that picture of Chanie makes me both angry and sad that he was one of so many children that lost their lives too early because of some messed up need to control them from religions and government. Thank you for writing about him and acknowledging his story and the stories of everyone you have been introducing us to.