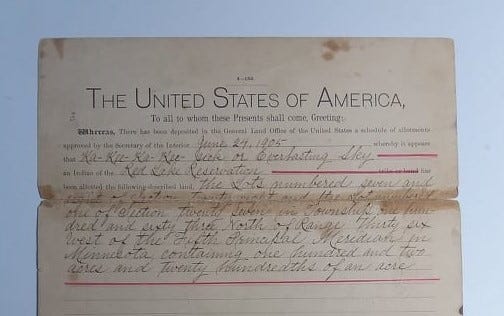

“Everlasting Sky” is an English transliteration of the Ojibway-language name used to refer to Kakaygeesick (1844-1968). His name appears above on the deed to Allotment 3.

Kakaygeesick is the conventional spelling in English used today by his great-great-grandchildren who carry his name and by the communities in and around Lake of the Woods. But it is not the only English spelling. On the document above it is spelled Ka-Kee-Ka-Kee-Sick.

There are many variations of his name used in historical archives and genealogical records. Gah Gay Keshig. Ka-ge-gi-jig. Ka-kay-geezhig. Kage gejig. For every version of the spelling of his name, I searched: one word, separate words, and various permutations with hyphens.

It doesn’t help that I don’t know the Ojibway language. Apparently neither did most of the Indian Census takers or church record keepers in the last century.

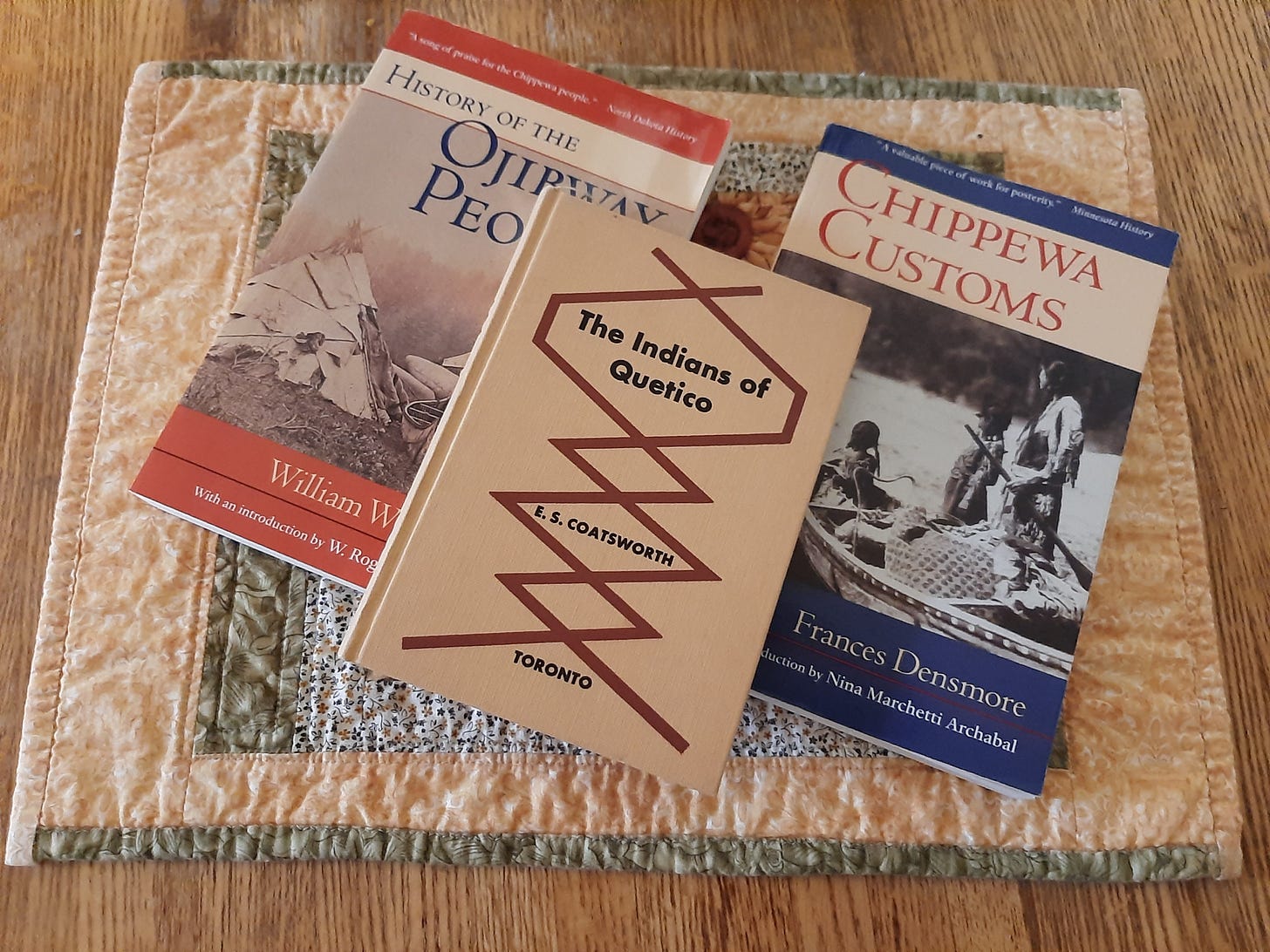

Even the word Ojibway has various spellings. Ojibwa. Ojibwe. It used to be spelled Chippewa. I admit it wasn’t until I started digging into archives in my late fifties that I made the connection that the Chippewa Indians I read about in college anthropology class in my twenties were the same tribe of people I met when I was a kid visiting relatives in Warroad, Minnesota.

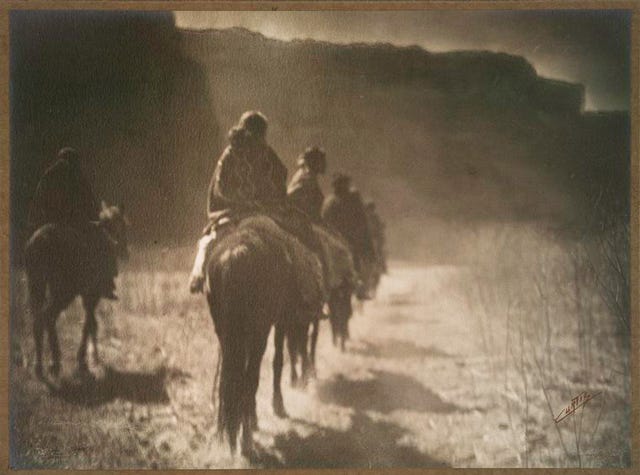

The lingering impression left by ethnographies I read 40 years ago is that of the “vanishing Indian.”

[Photo by Edward S Curtis, photographer, 1905, New York Public Library]

Being embarrassed I didn’t know Chippewa and Ojibway were two English names for the same tribe isn’t enough if I miss the lesson in my mistake. It’s what I was allowed to forget about the history of relations between nations on this continent: the myth of Manifest Destiny. This idea that territorial expansion by white settlers was preordained and inevitable. Even though I consciously reject the idea of Manifest Destiny, it infuses my language, attitudes, and beliefs unconsciously. Language is like that.

Ojibway is a word that means “puckered up” and likely referred to the style of moccasins worn with a gathered seam stitched across the top of the foot. Ojibway is a word others used to refer to people of this tribe, however, they refer to themselves as Anishinaabeg.

When searching collection databases like those held by the Gale Library of the Minnesota Historical Society, the general search term is spelled “Ojibway.”

But that’s not the real reason I choose to use this spelling for the name of the tribe. It’s because I asked Don and his brother John and sister Karen how they spell this word. The same for the spelling of their great-grandfather’s name and other words and phrases which come from their language and usage.

In all the records I have found about Kakaygeesick, one thing has been consistently reported. He never spoke English.

Thanks for sharing your research!

I find what you've written as a great example of one of the more insidious challenges that can make ancestral research difficult for descendants of immigrants, Indigenous kin, and enslaved people. The constant misspelling & alternative spelling of names by census recorders and the like is a systemic issue that (I think) speaks volumes on the disparities between the white settler colonial experience and the experience of everyone else living here.

Thanks again, best of luck in your continued investigations!

These stories of Kakaygeesick are fascinating Jill and so well-researched and informative. I love how you share here that, despite the disparities in some of the information, you've gone to the source - Kakaygeesick's own family. Really beautifully told. Thank-you for this.