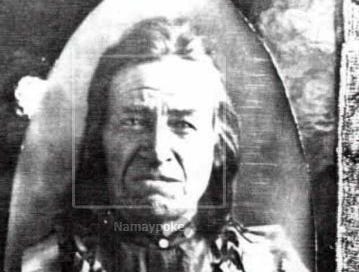

What did Chief Naymaypoke have to do with the Warroad Warrior mascot?

down the research rabbit hole to verify a local legend

In recent months I’ve heard a new version of how the Warroad Warriors got their name that simply doesn’t add up.

This version claims Chief Naymaypoke agreed to give or sell the land for the school if they would use the Warrior mascot.

If they would use the Warrior mascot? That makes no sense.

While there had been baseball competitions in Warroad since at least 1897, these were with groups of adult men against teams from neighboring communities. Warroad’s first inter-school athletic event was a baseball game against Roosevelt in 1913 (and Roosevelt won 14-11). Before there were even school athletic teams, Naymaypoke relinquished his land rights to the Warroad School District.

I have found nothing to corroborate the assertion that Chief Naymaypoke stipulated the school use the Warrior mascot.

Just because Naymaypoke isn’t the original source, doesn’t mean the entire thing is make-believe. How much can I verify to be true?

Warroad Public Schools are on the lands originally allotted to Naymaypoke. So there is some factual basis to the lore.

Did Naymaypoke give or sell his land to Warroad?

Several years ago at the Warroad Heritage Center, I saw a copy of a receipt for $150 paid to Naymaypoke. But nothing about the terms and conditions of the land sale.

Did Indian children attend Warroad Public School before or after Naymaypoke sold the school district his land?

I’d read that in 1898, Miss Gilbertson, the Warroad school teacher, “had many Indian children who could not speak or write English at the start of the term who were now doing work on a second grade level” (Warroad and Area 1897 - 1905 by Ole Swanson, 1983).

Swanson’s account suggests Indian children attended school even before the school district purchased the land in 1905; even before my great-grandparents arrived in 1903 to homestead at the Willow Creek settlement east of town.

But how many Ojibway children were enrolled? And in what years?

I didn’t know the answers despite years of research on the Warroad community because my focus has been on Naymaypoke’s brother, Kakaygeesick, and what happened to his allotment.

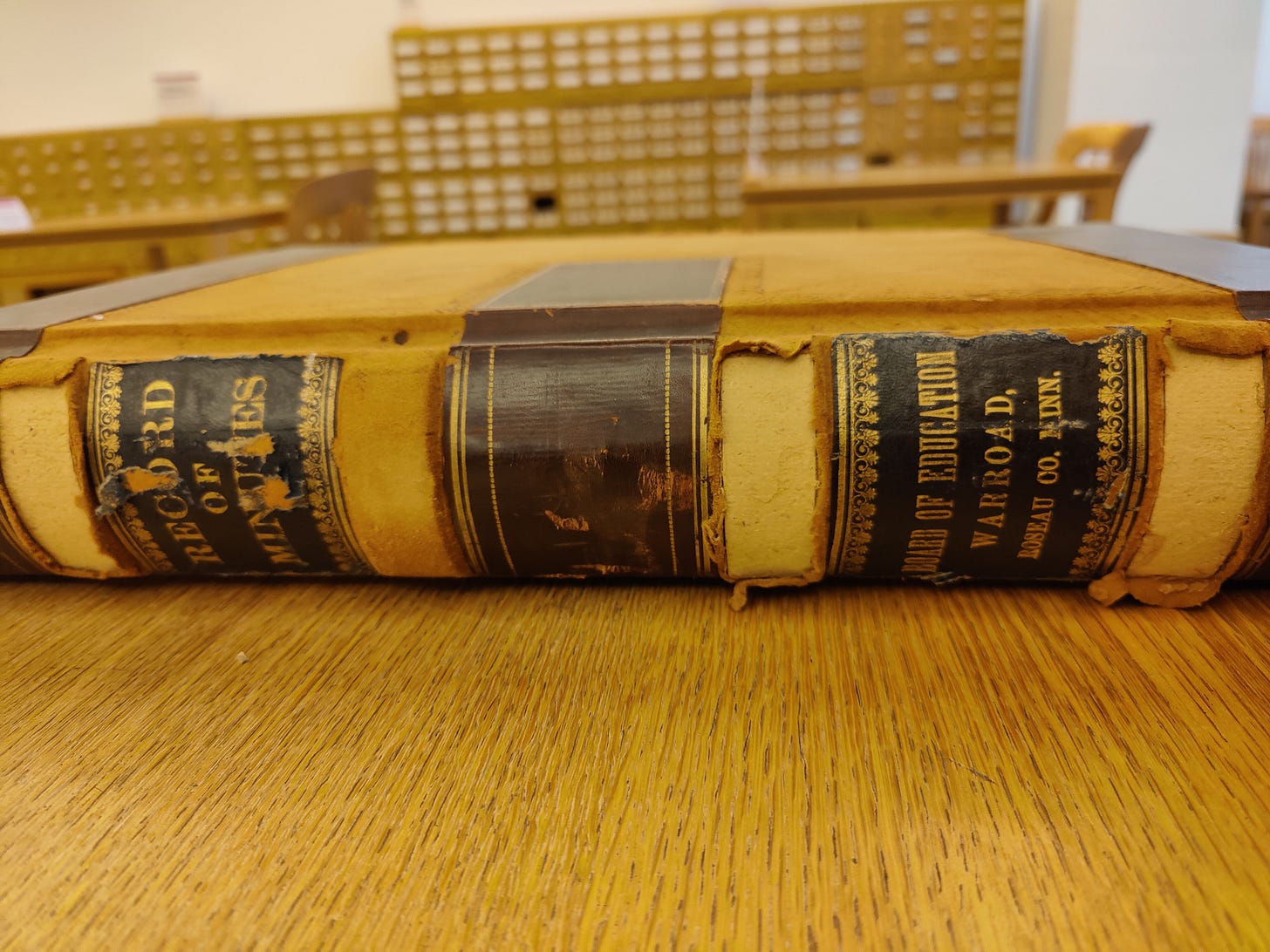

I searched online to see if anything popped up for Warroad school district records from the turn of the century. Bingo! The Minnesota History Center has the original documents starting in 1904 available for in-person viewing only.

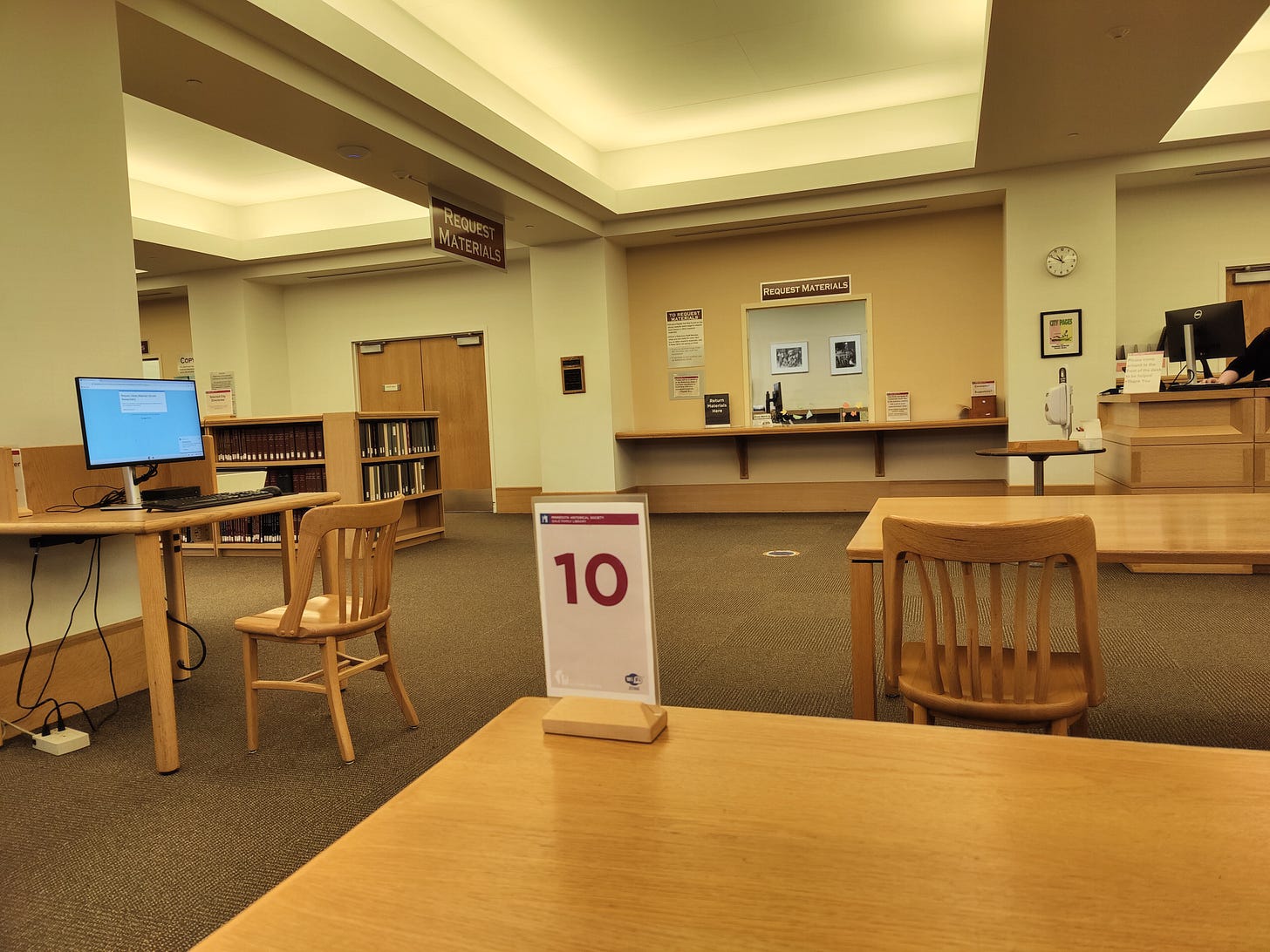

I wanted to go back to the Gale Family Library at the Minnesota History Center. There have been several trips to visit their collections and it is one of my favorite places to do research — white gloves and all.

Since it’s a four-hour drive to St. Paul for me, my sister, Barb Nelson, in Stillwater volunteered to go and take photographs of documents I wanted to see. I sent her the accession file numbers and she has spent days in the Gale Family Library at the Minnesota History Center.

She sent me hundreds of digital pages of school board minutes, attendance records, budgets, pupil files, public notices of meetings and bond issues, and photographs. There remain many more hours of studying these documents to make heads or tails of the real estate transactions, bond issues, and school building construction around the time the land became school district property.

It is fascinating to see parents’ names, occupations, and nationalities listed in the student records. Swedish, Norwegian, French, German, English, Irish, American and Canadian families appear on the list of pupil data. I plan to prepare a more thorough report of what I learn soon. One thing I did notice on my first reading of student records is the absence of Indian student names between 1904 and 1916.

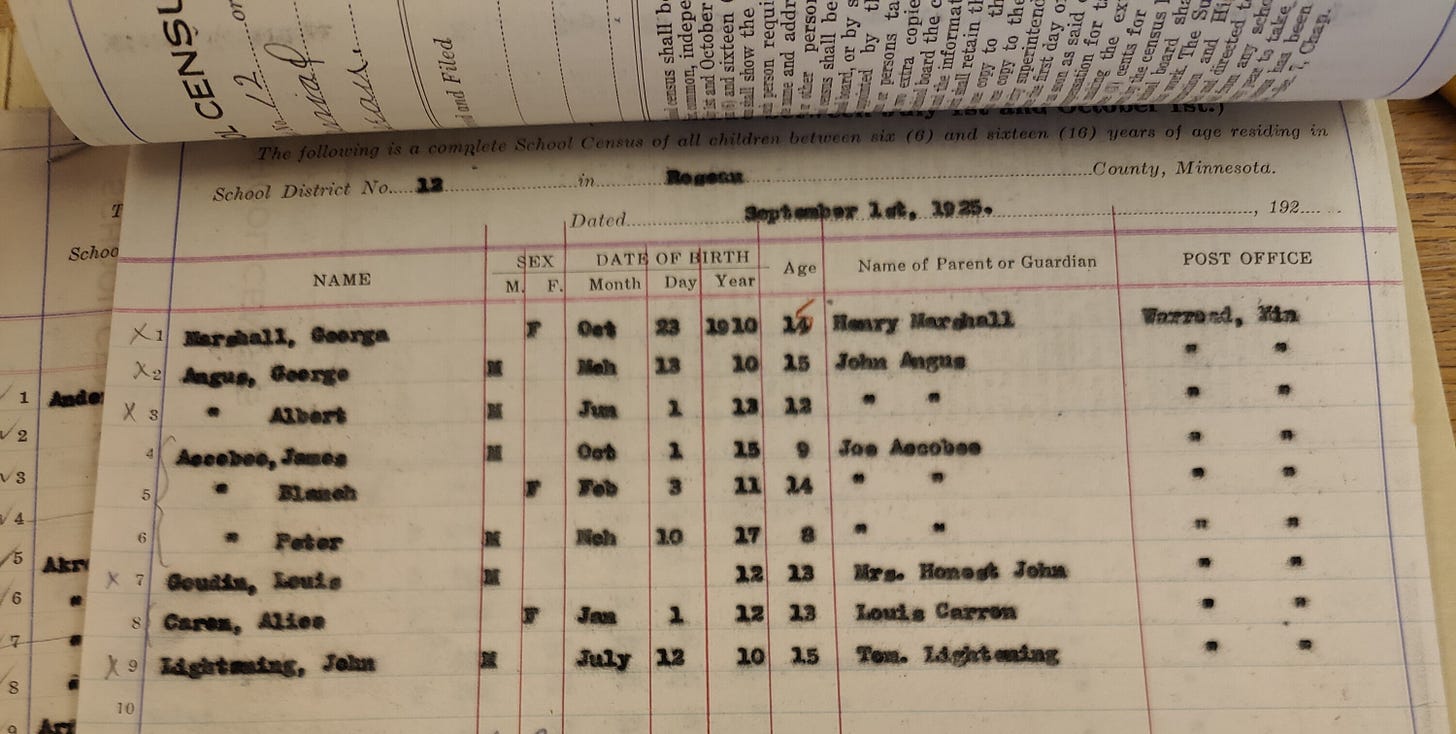

I want to share one interesting document I came across. The September 1, 1925, School Census page has a list of Indian students enrolled.

There is some evidence beyond what Miss Gilbertson is reported to have said in 1898. By 1925, Ojibway children did attend Warroad School.

The names of George and Albert Angus pop out at me because I recognize them to be the grandsons of Kakaygeesick; the sons of Mary (Kakaygeesick) Angus. The names of John Lightning and Louie Goodin are listed, too.

I recognize these four Ojibway boys’ names. Alvin (Ole) Swanson had written a description of one incident in a local history pamphlet, printed and distributed by Warroad’s State Security Bank:

When John Lightning, Albert and George Angus, along with Louie Goodin entered first grade they were told there were not enough desks so they would have to go home. John’s father, Tom, was not afraid to speak up, and he went to the school and offered to buy desks for the boys, of course the money was not accepted and the next day all four boys were back in school, seated at desks (Warroad Natives: The Chippewa, Ole Swanson, 1975: 54).

Swanson acknowledged that by the 1920s the state of Minnesota had an obligation to educate all of its citizens. He also acknowledged the local experience of that obligation.

For young Indian school students, recess, coming to school, and going home again was not a pleasant time, since they were often harassed by fellow students (Swanson, 1975: 54).

Yes, Indian children attended Warroad Public Schools, though the terms and conditions of their enrollment are not entirely clear. I am hoping to report on what I find or fail to find in these records. The facts presented in the documents I’ve read so far have forced me to think about some of the assumptions I have made.

I assumed for local Indian children that public school would be better than the Indian boarding school in Shoal Lake, Ontario, where some Warroad children were sent in the first decade of the twentieth century. The film adaptation of Richard Wagamese’s novel, Indian Horse, which I recommended last week, illustrates the inhumane conditions Margaret and Hans Lightning of Warroad must have experienced as children there. Is it better to be in a situation where every student is treated badly or to live where only some students — those who are Indian — are treated badly?

I assumed for local Indian children that public school education would be beneficial to them. I hadn’t thought about possible costs to their culture, language, and customs. Who benefited from Indian children learning English and gaining skills making them suitable for employment? What did it mean for the Kah-bay-kah-nong to have their children learn English, be schooled, and assimilate?

I assumed Chief Naymaypoke in agreeing to transfer the land to the Warroad School District did so voluntarily and because he supported public education. That is one big whopper of an assumption for which I have no more evidence than I do for Naymaypoke requiring the school use the Warrior mascot. How exactly did the school board acquire Naymaypoke’s land?

I don’t yet have answers to all my questions. But I have some hot new leads. I hope to spell out some preliminary answers in the coming weeks.

Note of gratitude to my sister for the research assist.

You have done so much research for this project! I think that's an amazing accomplishment and I admire your dedication. In my own experience, when we start asking questions and digging for something we want to know, we can't help but find more than we bargained for. Don't be surprised by more surprises 😁

Interesting! Love how you pulled your sister in to the research :-)