What Kevin Costner's HORIZON has to do with Warroad's first school

and why Indian students stopped attending after 1900

While European fur traders and missionaries frequented the trading post in the Ojibway village of Kah-bay-kah-nong for almost two centuries, most had not become permanent residents.

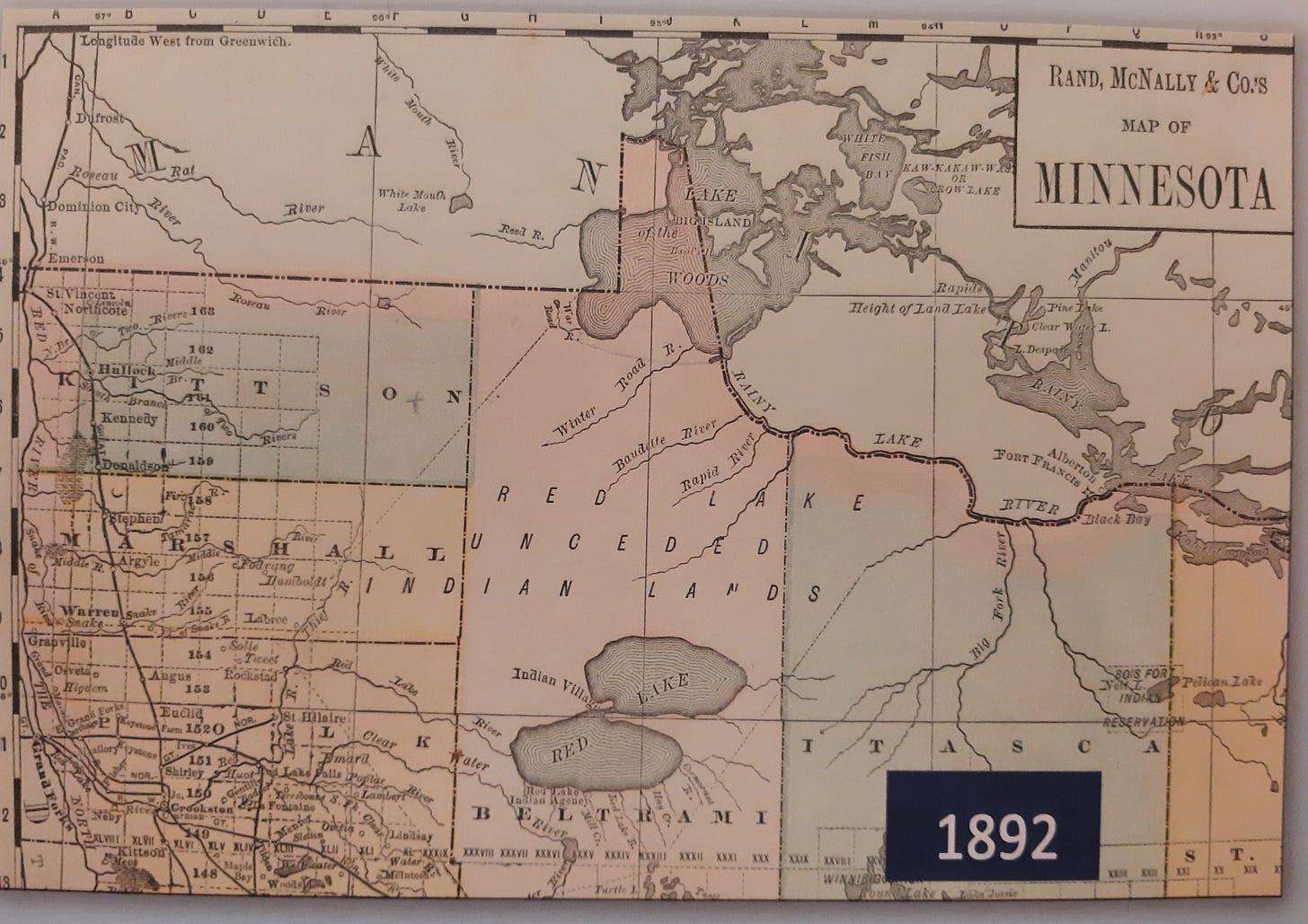

While Congress enacted the Homestead Act in 1862, thirty years later the territory from Red Lake to Lake of the Woods had not yet been opened to homestead claims.

In this respect, Manifest Destiny happened late and all at once here in the remote wilderness of northwestern Minnesota.

This 1892 Rand-McNally map exhibited in the Roseau County Museum clearly indicates the land at the south end of Lake of the Woods as “Red Lake Unceded Indian Lands.” The town of Roseau is in Kittson County.

On December 31, 1894, Minnesota Governor Knute Nelson established Roseau County, dividing Kittson County in half. Then in 1896, Roseau County annexed land east of the county seat to Lake of the Woods, taking part of unceded Beltrami County.

Roseau County Auditor Charles Moody had advanced the cause of annexation with Albert Berg who came to visit Warroad from Chisago City. Albert Berg had become Minnesota Secretary of State in 1895. Both men would move their families to Warroad in 1897. Their actions violated the treaty agreements which the US had made with the tribes, but they proceeded anyway.

Four families from Roseau moved into the Ojibway village known as Warroad in the spring of 1897. Others followed.

In the fall of 1897, Miss Rena Gilbertson taught 24 students in the schoolhouse. Half were children of white settlers and half were Indian or Métis. In the second year, only five of the 36 students were Indian or Métis. In the third year with 45 children enrolled, 15-year-old Grace Naymaypoke is the only Indian student. Then there were none.

Indian children did not attend Warroad School for four years before and for 20 years after Naymaypoke relinquished title to his land on which the public school sat.

They vanished from the records of a school which sat on land where they resided. This doesn’t fit the assimilation story of local legend. Nor does it conform to the myths about the settlement of the American frontier.

After immersing myself in primary documents from the 1890s to 1910 in the archives in Warroad and Roseau for two weeks, I’ve come to know the main characters, their desires, and deeds. There is so much to unpack.

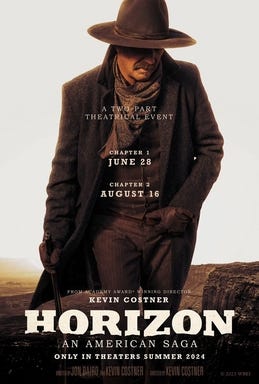

I’m calling it my Kevin Costner problem. I’m no Kevin Costner, but I can relate to his challenge of working with a large ensemble cast of flawed characters, complicated subplots, and a saga which doesn’t fit the formula of the story we think we already know.

Have you seen his new film, Horizon? I confess, I appreciated the reprieve from the heat on a summer afternoon, perhaps more than the script. The film tanked at the box office in its theatrical release.

For good reason. It failed to deliver a coherent story in three hours. But I give him credit for setting out to show audiences a Western that isn’t glorifying Manifest Destiny, but exposing it.

I heard David Remnick of The New Yorker interview him before the film’s release and Costner talked about the premise of the first chapter in his American saga. White immigrant families are lured west by land speculators who promise them free land to farm and the rise of new cities. They arrive in Indian territories long before they were open to land claims. Costner cuts away to the point-of-view of tribes who see the “giant population that continues to roll toward them, and they think of it as unbelievable.”

The film enacts the history of encroachment. To encroach is to trespass and take possession gradually and without being noticed. That describes what happened in the early days of Warroad.

Naymaypoke could never have anticipated the numbers of white settlers to come when he first allowed a schoolhouse to be constructed on his land in 1897. Enrollment jumped each year: 24, 36, 45, then 53 students in 1902-1903 to 110 students in 1903-1904.

The school attendance and district board meeting minutes show how quickly whites dominated by sheer numbers. By 1901, twice as many white settlers resided in Warroad as Indians.

Newcomers kept arriving by train, stagecoach, steamboat, covered wagon, horse and buggy; including immigrants from Canada and Europe. In 1902, this territory opened to homesteaders. Albert Berg and Charles Moody were the first in line to stake their official claims.

Though I found no documents banning Indian or Métis students in school records or newspaper accounts, it seems likely such a rule did not need to be spelled out in writing. There is no written school board policy which required female teachers be single women either. This social convention did not need to be documented for it to be in effect. And there is no written policy the language of instruction be English. Yet it was.

Costner’s film makes it easier for me to understand why Indian students stopped coming to the school on Naymaypoke’s land long before he relinquished title to the property to the Warroad School District in 1905. But Costner also tries to show what encroachment looked like on a human scale, in the actions of individual characters.

As I pored over the school records from these earliest days of the schoolhouse, I had to wonder if a change in teachers precipitated the drop in enrollment of Indian and Métis students between the first and second year at the schoolhouse.

Miss Florence Dowsland replaced Miss Gilbertson after the first year. She had recently arrived with her parents, Penny and Ralph Dowsland. The Dowslands had emigrated from England and raised their six daughters farming in southern Minnesota. They planned to spend their remaining years in the town of Warroad.

After her second year of teaching in the Warroad School, Florence Dowsland married Thomas Lawson, who co-owned the Jones & Lawson General Store. Her sister, Edith, married Tom Jones, of Jones & Lawson, who had been a school teacher. Another sister, Lena, married Charles Moody, who would soon be president of the new independent school board in 1904.

Moody, Jones, Lawson, and Albert Berg had appointed themselves members of the first school board and worked to secure the deed to Naymaypoke’s allotted parcel of land on which the school had been built. Albert Berg served as cashier and director of The State Bank of Warroad which issued the $150 check to Naymaypoke.

The reason to gain the deed to this property was to fulfill the requirement by the State of Minnesota to issue school bonds: ownership of the land and an existing schoolhouse by a public school district. In order to gain financing for the construction of the new schoolhouse which opened in 1905, the school board members sought to purchase the land they had encroached.

I plan to take the next two weeks off from publishing new posts here in order to address my Kevin Costner problem. Er, I mean to review my new research findings and spend more time writing. It takes time to listen to the facts and let them speak for themselves. Even more time to understand what they mean.

Plus, it’s July.

Thank you for reading my weekly glimpses into this research about the history and culture of this special place to which I have a fierce attachment.

I have some extraordinary stories to report next month.

Well done Jill!

You're moving history beyond the recounting of facts into a reckoning with how our society evolved into its current state. I look forward to reading your analysis.

I know, I know, I know, but I just want to say "Manifest Destiny" while very real and toxic just makes by blood curdle.