[Me in the fields of On Warren Pond Farm in upstate NY, c. 2010. Photo credit: Gary Hodges]

The idea of homesteading always sounded romantic to my inner second-grader who fell in love with reading when she discovered the Little House on the Prairie series by Laura Ingalls Wilder. But what did I really know about homesteading?

A homestead is an owner-occupied residence and that real estate designation provides financial and legal protections to the owner. The sanctity of the home as private property has been written into laws and tax codes. If you’re a home owner, it’s likely you get a tax break on your primary residence under a homestead exemption.

Homestead is a word I had associated with sustainability, self-sufficiency and self-reliance. These notions came more from reading Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson than chopping wood or pulling beets. Then I fell in love with Sam Warren, a bachelor goat farmer in the Finger Lakes of upstate New York. When he put indoor plumbing in his 12’ X 20’ cabin, I moved in. My personal philosophy became to produce what you consume, grow organically, think globally and act locally.

[Our rustic homestead, c. 2004.]

In more recent years, homesteading seems to have become code for the lifestyle of survivalists and apocalypticists. My great-grandparents homesteaded in northern Minnesota and for me that conjured up an image of living in a log cabin in the woods. All these connotations to the word homesteading, however, whitewash its meaning in US history.

In April of 1861, the Civil War started.

In May of 1862, Congress enacted the Homestead Act.

Under the Homestead Act, any citizen or immigrant of adult age could claim 160 acres provided they had never borne arms against the US. The government offered free land to those who sided with the Union.

As a Yank, I am too eager to point fingers at white Southerners for the exploitation of Black labor permitted by the then legal institution of slavery, when the log in my eye blinds me to the economic reparations of free land to northern homesteaders, like my immigrant great-grandparents. By free land, I mean they didn’t purchase it for cash; though I recognize how those words make it sound as though it didn’t come at a great price to those from whom it was taken.

A lot happened between the passage of the Homestead Act in 1862 and 1903 when Charlie Kling, my maternal great-grandfather, arrived with his family to stake his claim in northern Minnesota. The Civil War, the Great Sioux Wars, the completion of the transcontinental railroad and a land rush on ceded Indian reservation lands.

Charlie Kling was a bit of a latecomer to homesteading. Even though this federal program offered land for a minimal filing fee and a lot of sweat equity, it was not a panacea for poverty. Few could afford the tools, livestock, seed and feed to make a go of it.

Most of the land went to speculators, cattle owners, miners, loggers, and railroads. Of some 500 million acres dispersed by the General Land Office between 1862 and 1904, only 80 million acres went to homesteaders. Indeed, small farmers acquired more land under the Homestead Act in the 20th century than in the 19th (National Archives).

The Homestead Act required claimants to live on and “improve” their plot by cultivating the land for five years before they received title to the property.

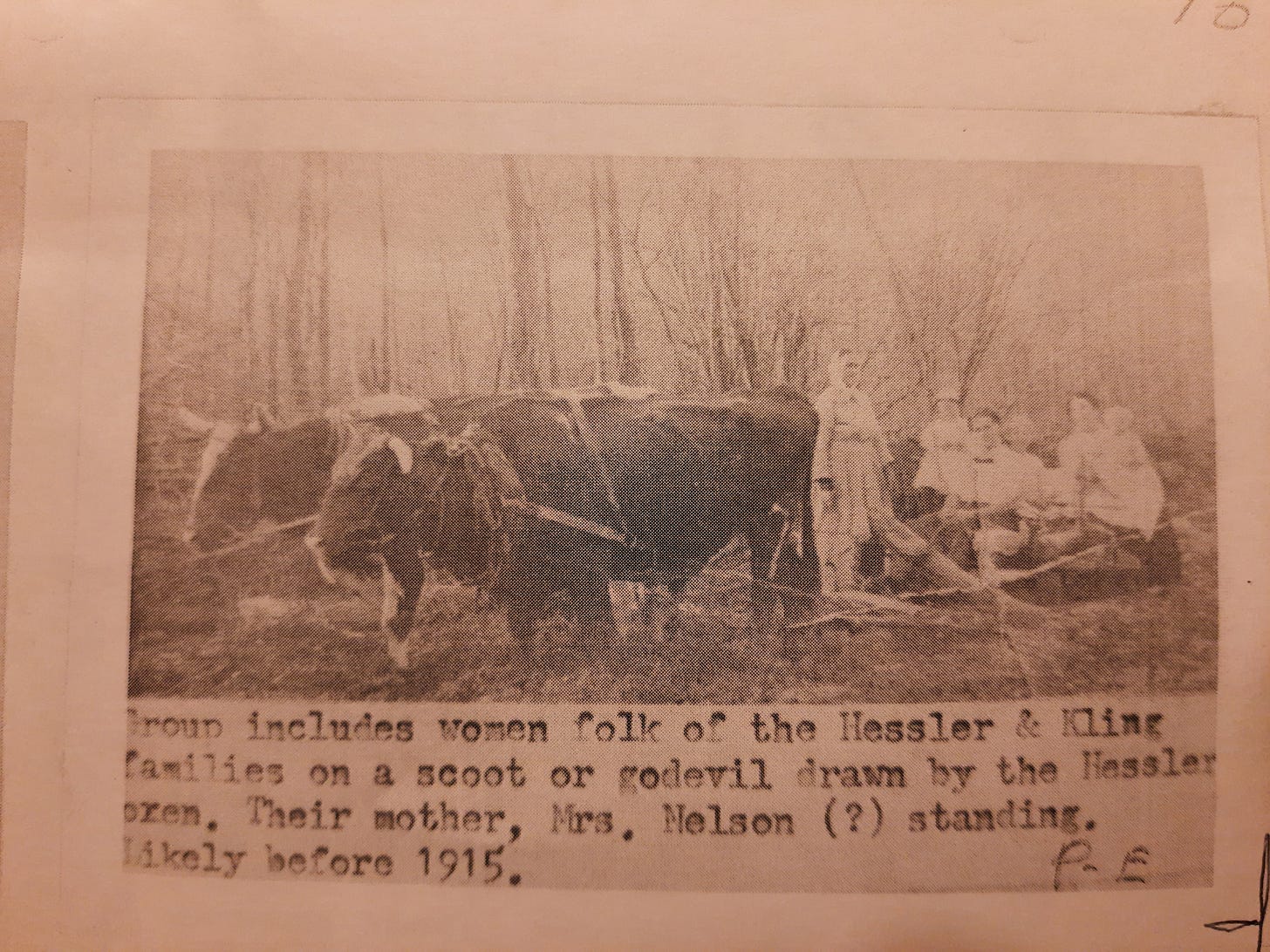

[Photo from Lest We Forget, T.E. Helmstetter, fourth printing, 2005.]

I had thought of my maternal great-grandparents Charlie and Ellen Kling as family farmers. But before fields could be planted, the forest had to be cleared. Charlie Kling spent most of his days for decades cutting timber, the real cash crop. Farming this far north on fine sandy loam wasn’t easy. By the 1930s, the federal government relocated 430 settler families in the area after their homestead lands were determined to be unfit for agriculture.

Free and clear title to an allotment required Indian claimants remain in permanent residence for 25 years and “improve” their plot by farming.

Understanding the origins of homesteading and its relevance to my property tax bill today helps me connect the story of my great-grandparents with what has happened to Kakaygeesick’s Allotment #3.

Thanks for these photos! I can’t unsee your prairie dress!

I came to my interest in the Ojibwe of Northern Wisconsin in a similar way. Back in the late 2000s, my family and I bought a house on Lake Montanis, just outside of Rice Lake. My quest to learn the meaning of the lake's name introduced me to Aazhaweyaa (Montanis) and her family. I recommend Erik Redix's The Murder of Joe White if you're interested in more of that story. https://birchbarkbooks.com/products/the-murder-of-joe-white