When looted artifacts return home

empty exhibits might open up museums to reconcile with the past: theirs and ours

Last month on a trip to New York City, I went to The Metropolitan Museum of Art on a Sunday afternoon with a friend.

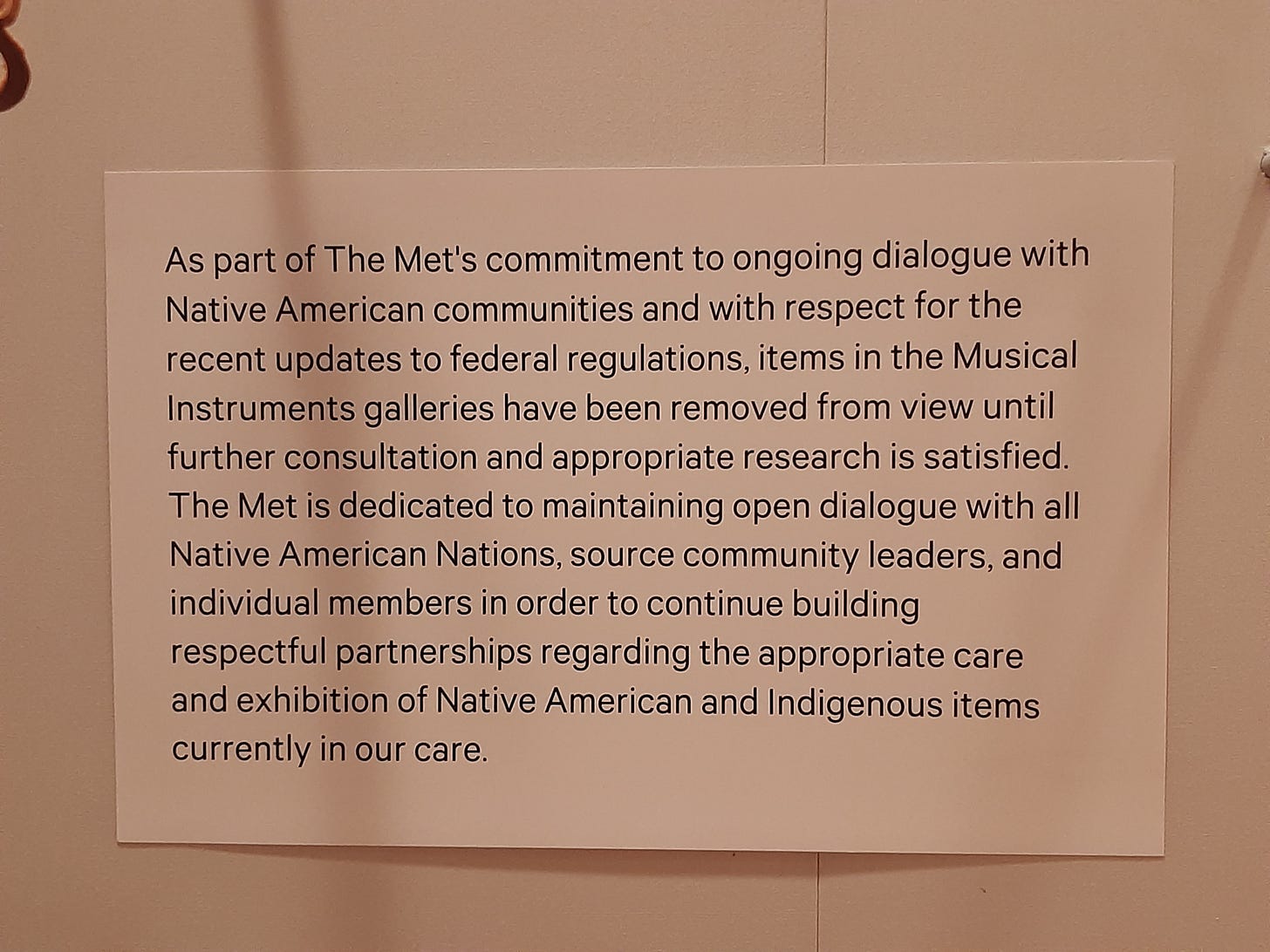

In the galleries of musical instruments on the second floor, we came around a corner and found this. An emptied exhibit.

What? Had these museum pieces been some of those stolen from Cambodia? I remembered reading recently that The Met would repatriate some of its Khmer-Rouge era works.

I avidly follow the research adventures of art crime expert Erin Thompson, associate professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. In early February The New York Times published her op-ed, “Mighty Shiva Was Never Meant to Live in Manhattan.” She explains why it is worth it to repatriate stolen and sacred objects even if it means empty exhibits: “Keeping these artifacts in our museums will not help us experience more meaningful connections. But helping bring them back home just might.”

Here I was two weeks later at The Met and curious to see what this meant. On the second floor heading toward the section with Asian Art, we were passing through displays of musical instruments and came across this emptied exhibit.

The objects had been removed from public display in compliance with the federal process of repatriation of looted art and cultural artifacts begun under President George Bush in 1990. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act established protocols to follow, including the return of human remains, funerary objects and other cultural artifacts.

After 30 years of institutional resistance and delays, Congress approved new federal regulations which went into effect in January 2024 and now require museums and institutions to comply with step-by-step procedures with mandated timelines.

In January the American Museum of Natural History had closed two exhibition halls — Eastern Woodlands and Great Plains. The Field Museum in Chicago covered display cases.

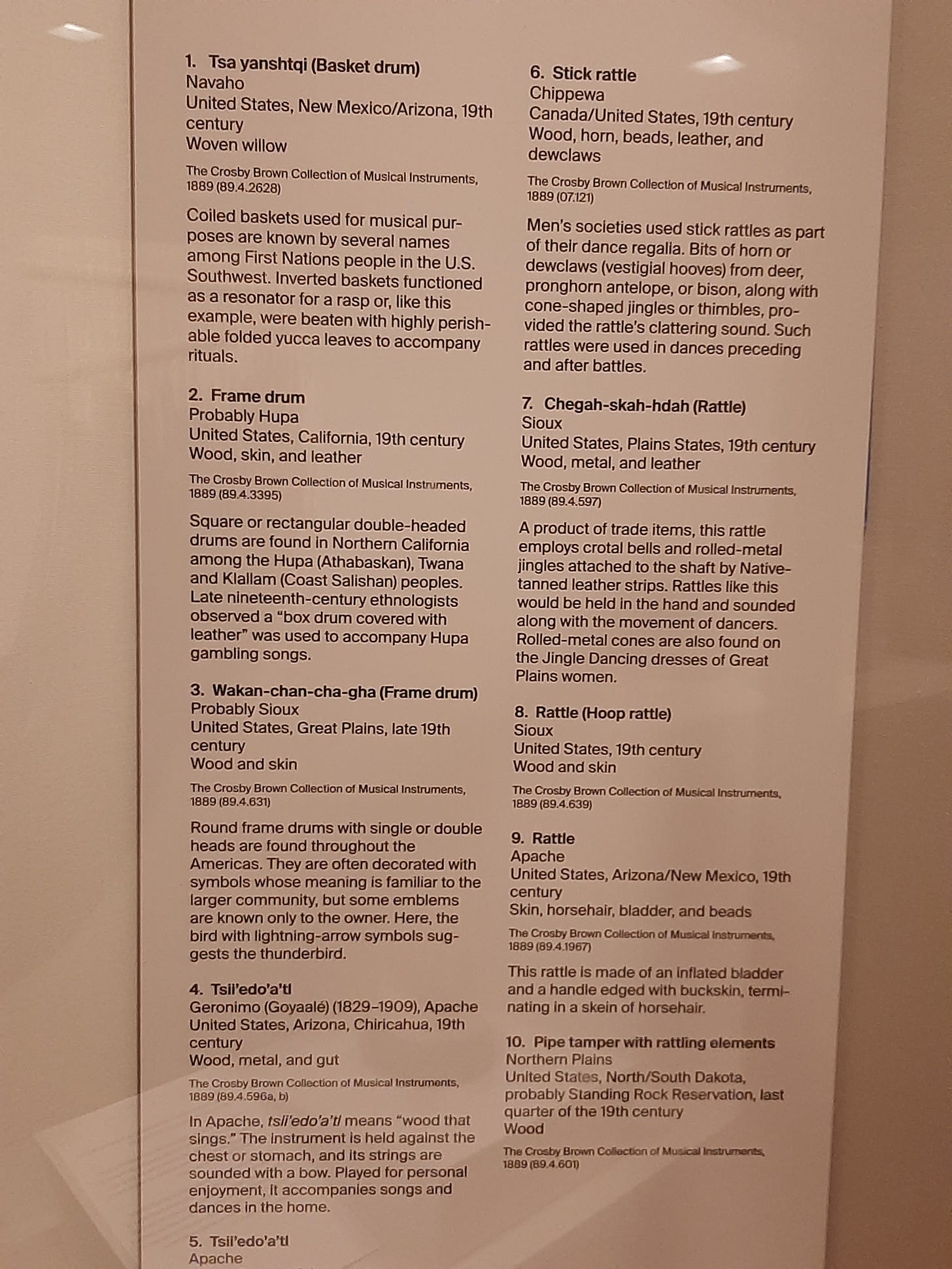

Here’s what I found had been removed from The Met in this exhibit:

All of these are from the Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments. Instruments? These drums and rattles are sacred objects, used in ceremonies.

The collection is named after John Crosby Brown, a wealthy investment banker. His wife, Mary Elizabeth, was the daughter of John Adams, a Presbyterian minister who became president of Union Theological Seminary in Manhattan. Mrs. John Crosby Brown had begun in the 1870s to collect “instruments of savage tribes and semi-civilized peoples” on her travels and excursions. She donated her collection to The Met in 1899.

How a particular object came to be part of her collection would seem essential to understanding its meaning, significance, and history. And I was particularly interested in one object. Item 6.

I searched the online gallery of The Met for the Stick Rattle identified as 19th Century Chippewa from Canada/United States. Here is what I found:

The image. Stunningly beautiful. It is as if possession were the point. There is no additional context provided.

What did museum archivists learn from it in the hundred-plus years since they acquired it? How was this stick rattle used? Who made it? Where was it made? Do those beautiful blue beads date the piece after Ojibway traded with Ukrainians in Ontario? The rattles are made of dew claws, but it does not specify whether the ones attached to this stick rattle are deer, elk, or bison. By 1882, the bison population had collapsed. The placard claims the rattles were shaken in battle. Were they? Rattles are part of many spiritual ceremonies. Can we find the descendants of the people from whom this stick rattle had been acquired? How did this sacred object come into the possession of Mrs. John Crosby Brown? What lessons do we need to learn? How can we begin to repair harm? How can we make sure this never happens again?

Museums don’t need to have the actual objects on display to create educational, even entertaining, exhibits and programs about their collections which engage communities, including those from whom objects were taken.

The process of returning looted or sacred objects by museums could serve to connect people in new ways. Museums could display replicas or use photographs or produce videos of the people to whom they have been returned, adding their voices and stories to their collections. Museums can commission new works by contemporary artists, train and assist in the conservation and exhibition of cultural and historical artifacts from a broader spectrum of experiences and perspectives, and guide their patrons in reparations research.

Art crime scholar Erin Thompson suggests empty exhibits create spaces for museums to hold the conversations necessary to reconcile with the past: their own and ours. But I didn’t see it happening at The Met on a Sunday afternoon with thousands of visitors in the building. Instead, I watched my fellow museum-goers simply walk on by. Nothing to see here. Move on.

I completely agree with you. I think your article could inspire the kind of questions people ask of their museums. I am going to share it with my friend, John Immerwahr, who has produced a number of wonderful short videos related to exhibits in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. His son, Daniel has had several articles in the New Yorker and New York Review of Books. Daniel is a superior historian/writer from Northwestern University. https://johnimmerwahr.org/projects/ and her is a link to one of the videos featuring Daniel, and it's really tremendous: https://youtu.be/TnI4l6rFuHI?si=mGUq9RfgXrc7MuBb

Well said! I agree, those empty spaces should inspire questions and conversations about where the pieces come from and why they are no longer on display. We can learn from empty spaces. Thank you for this.