You might not know much about allotments. I know I didn’t when I started to research how and why Don Kakaygeesick and his mother could be displaced from their home in 2012 when they had his great-grandfather’s will and original documents to the allotment.

Allotments are not something most non-native people know much about, although the recently released Scorsese film Killers of the Flower Moon brought new attention to the topic. The title of the film was taken from a nonfiction book by David Grann about the origins of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and its first case: investigating the multiple murders of Osage Indians for their allotments to land rich in oil.

While this short essay may not have everything you want to know about allotments, it’s what I had needed to know in order to understand the history of this land where Don’s great-grandfather and mine lived.

Anton Treuer in his book, Everything You Wanted to Know about Indians But Were Afraid to Ask (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012) offers a clear definition:

Allotment is the practice of taking tribal land, which was held in trust for the common use of all tribal members, and splitting it into parcels to be owned by each tribal member, with the remaining land sold to settlers and private companies. The profits from the land sales were then to be used by the Department of the Interior to fund assimilation programs for American Indian people. The Dawes Act enabled this policy on tribal land in the United States in 1887. Of the 155 million acres of land held in trust for Indians on reservations, 50 million were allotted to tribal members, usually in 160-acre parcels. The remaining 105 million acres of land were deemed “surplus” and opened for white settlement (Treuer, 2012:91).

The General Allotment Act of 1887 came 15 years after the Homestead Act. And in some limited respects, allotments were similar to homesteads in that they had to be owner-occupied and the land cultivated. But they were fundamentally different in that the Homestead Act offered free land to white settlers while the Allotment Act took unallotted Indian land to give to homesteaders.

After more than a century of making and breaking treaties and waging war, the US government fundamentally pivoted its policy towards Indians with the General Allotment Act.

There was a shift from extermination to assimilation.

There was a shift from negotiating with tribes to treating Indians as individuals.

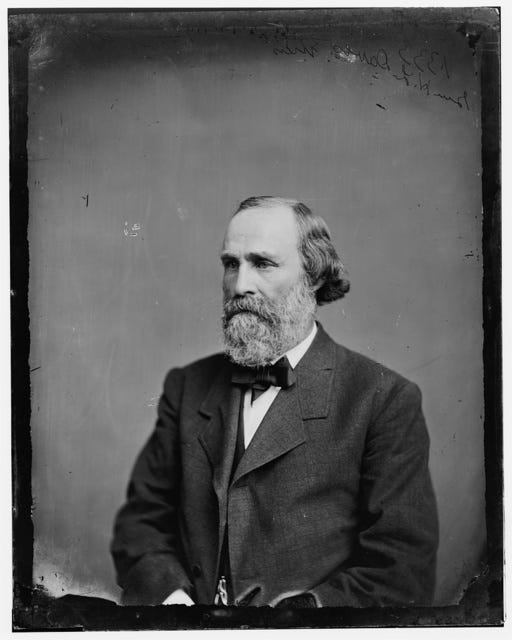

[Senator Henry Dawes, Library of Congress.]

Often referred to as the Dawes Act, after Massachusetts Senator Henry Dawes who served as chairman of the Committee on Indian Affairs, the 1887 General Allotment Act meant Indians would own their own land. This tempered the early American spirit of Manifest Destiny in which white settlers believed themselves divinely ordained to settle the entire North American continent.

Senator Dawes wanted Indians to achieve self-sufficiency and he thought homesteading their land was the best way. He continued to promote the tenets of westward expansion and applied American individualism and property rights to the “plight of the Indians.”

This shift in policy meant dividing up land held in common by tribes and in so doing diminishing their collective power to hold the US government accountable for its treaty obligations and agreements. At the same time, it also shifted accountability to individual Indians and away from the US government. The sale of “surplus” reservation land was distributed among tribal member allottees in equal portions.

Allotment papers established a particular parcel of land was held in reservation trust by the US government which deemed Indians incompetent. Only after twenty-five years (instead of the five years required of homesteaders) could an individual allottee apply for title to the land.

Two tribes, the Menomonie of Wisconsin and the Red Lake band of Ojibway in Minnesota, refused to accept this new policy of allotments when Congress passed the Dawes Act.

It was Medweganoonind (He Who Is Spoken To) who made sure Red Lake Reservation was exempt from the 1887 General Allotment Act. The US government knew by 1889 Red Lakers weren’t going to move, so Medwegannonind, head of the seven hereditary chiefs of Red Lake Nation, agreed to cede lands in the north as long as there were no allotments.

That land ceded by Red Lake Reservation in the north is where my great-grandparents settled.

Despite their agreement with Medwegannonind, the US government issued three allotments to three brothers for land in the north, on Muskeg Bay of Lake of the Woods.

I'm learning so much I didn't know from reading your Substack on the fairly unpublicized and unknown history of our country. Details matter--and your posts are personal and historical, connecting the past with the present to help make us all aware of injustice and how it spawns so many tragedies.

Thank you for this! So important to understand the real history of our country.