Naymaypoke's great-grandson adds missing piece

Roy Jones grew up in the house built for Naymaypoke

“Hi, I’m calling to talk to whoever wrote these articles about Naymaypoke,” began the voicemail.

In September, Roy Jones from Florida called and left me a message. I called him back. He told me he grew up in the house built for Naymaypoke.

I asked Roy how he had found my Substack. Turns out Henry Boucha’s former wife, Elaine, who is a subscriber, printed out a copy and mailed it to him. (Thanks, Elaine!)

Roy Jones, 88-years old, is a great-grandson of Naymaypoke. I immediately recognized his name and knew exactly where to find him on Chief Ay Ash Wash’s family tree and now here he was on the telephone with me.

Naymaypoke’s daughter Anna had married John Jones. Jones had come to Warroad from the Scottish-Métis community of Selkirk, Manitoba. Anna and John Jones had two children, Max and Sally. Max was Roy Jones’s father.

Roy Jones has asked some of the same questions I have had about what happened to Naymaypoke’s land. And he asked decades before I did.

Roy told me he had photocopies of documents he obtained from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, D.C., before a fire in 1986 destroyed a significant number of historical records. He sent copies to me.1

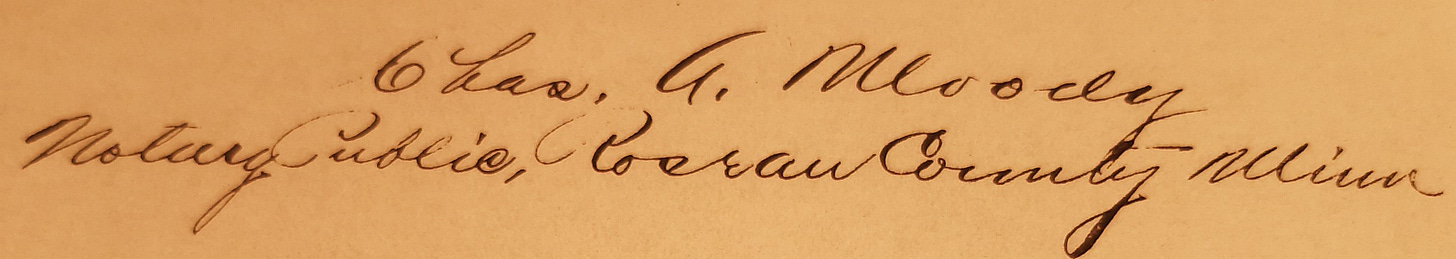

Immediately upon opening the envelope, I recognized the handwriting on documents filed with the U.S. Land Office in Crookston, Minnesota. Sure enough, I see the signature of Chas. A. Moody.

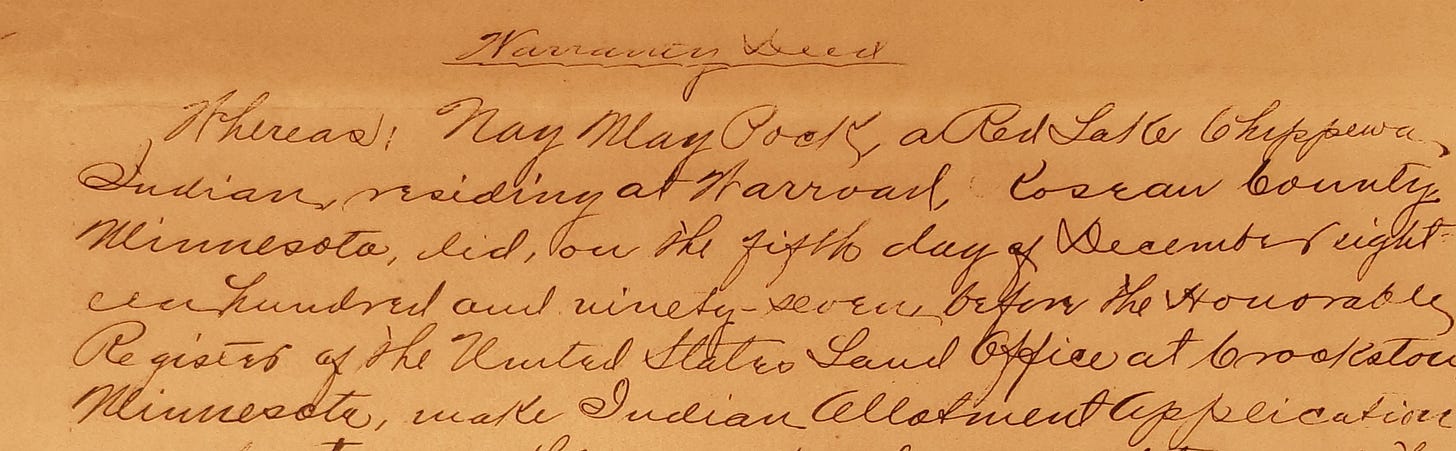

One document immediately caught my attention. The Warranty of Deed signed April 28, 1905, which concluded the transfer of a four-and-a-half acre parcel of land from Naymaypoke to the Warroad School District. It was certified by the Register of Deeds in the Crookston land office.

This document is important for a few reasons.

One, it establishes a timeline.

Naymaypoke first submitted an allotment application to the Land Office in Crookston on December 5, 1897. This is when the first schoolhouse in Warroad opened and it would be seven years before the school district paid Naymaypoke for the land on which it stood. The process of land transfer began shortly after the annexation of unceded Red Lake Reservation land into Roseau County in 1896.

The era of forced removal of Indians had largely come to an end with the passage of the Allotment Act in 1887. The federal government no longer negotiated treaties with tribes but adopted land policies which considered Indians as individuals instead of nations. Moody and other settlers in Warroad knew the original residents of the Ojibway village could not be forcibly removed to the diminished reservation about 100 miles south. And settlers had no reason to dislocate or dispossess them, according to hundreds of early Roseau County pioneer family accounts which describe many interactions as beneficial and necessary to their welfare. There was plenty of acreage available to set aside some for them and the federal allotment system provided the method to designate it as off-market to new settlers.

Two, it establishes the legal basis for the transfer of ownership to the Independent School District 12 of Warroad, Minnesota.

By the power conferred by “an Act of Congress” which enabled independent school districts to purchase certain lands,2 the purpose becomes clear. In order for the Warroad School District to issue bonds for the construction of a bigger schoolhouse, the state of Minnesota required the school district already operate a schoolhouse and own the property on which it exists and provide evidence of such. It is this Warranty of Deed which secured state financing.

The deed refers to the Allotment Act of 18873 and the 1902 legislation “to provide for allotments” to Indians in Minnesota.4 Yet there weren’t supposed to be any allotments to Red Lake Reservation as it had been exempted from the Allotment Act; the land is held in common by the tribe. Yet the Warranty Deed identifies Naymaypoke in its first sentence: “Whereas, NayMayPock, a Red Lake Chippewa Indian, residing at Warroad….”

Allotments were entrusted with the federal government for 25 years during which the land could not be sold. In order to gain a clear deed, the Indian allottee had to remain in residence, farm and improve the land, assimilate, and make a formal application.

Three, it suggests why the allotment applications gained approval only seven years after submission.

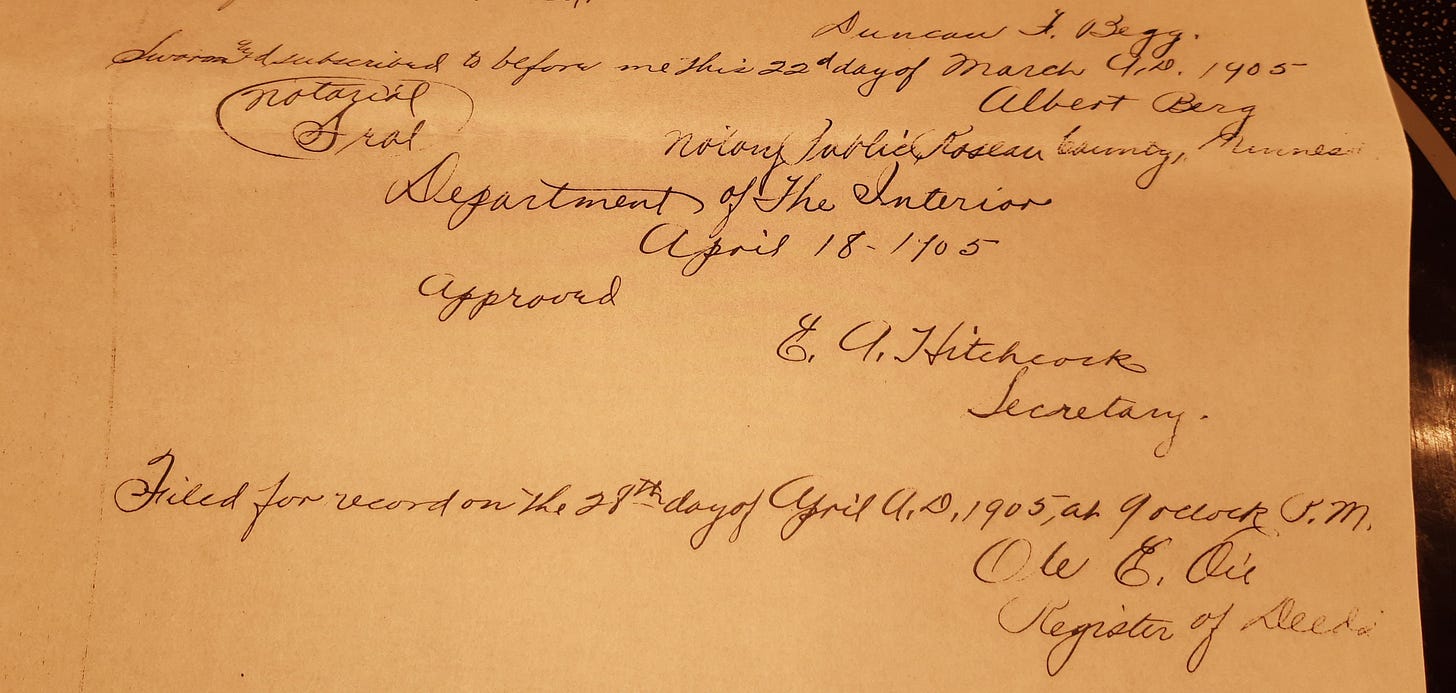

When I had found the school district records earlier this year and saw the records of the cash sale transaction, I hadn’t been able to determine how they had gotten around the proviso which required the Secretary of Interior approve the sale in order to gain a clear title without the restrictions of an allotment. The Warranty of Deed indicates such approval had been obtained soon after Naymaypoke had signed the sales agreement in late March of 1905.

At the bottom of the deed it is noted: “Department of the Interior, April 18, 1905. Approved, E. A. Hitchcock, Secretary.”

Why did the Secretary of the Interior overlook the treaty agreement with Red Lake with regard to the exemption of allotments? Why had it taken seven years for the applications for allotments to be approved? Had the formal request from the Warroad Independent School District to purchase Indian land for the purposes of education persuaded Secretary of Interior Hitchcock to approve the allotment applications in order for this parcel of allotted land to be sold?

While I could find nothing further in Secretary Hitchcock’s letters archived at the Carlisle Indian School, what letters I did find suggest strongly he would not have objected to the transfer of Indian land into the hands of white settlers for the purpose of providing public education for those settlers’ children.

Roy Jones sent a packet of documents which I am still reviewing, and today I want to focus on this document.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 established the mechanism for funding public education.

An act to provide for the allotment of lands in severalty to Indians on the various reservations, and to extend the protection of the laws of the United States and the Territories over the Indians, and for other purposes, Public Law 119, U.S. Statutes at Large 24(1887): 388.

Congressional Record. Volume 35 March 4, 1901 to July 1, 1902, History of Bills and Resolutions, S4340, HR8190. https://www.congress.gov/57/crecb/1901/12/02/GPO-CRECB-1902-pt9-v35-3.pdf

The stories you are unraveling are very significant, but as meaningful to me are the relationships you are building with people like Elaine and Roy Jones.

I really appreciate your articles as does my extended family. I have the picture you posted of my great grandmother Anna Namaypoke hanging in my home and my niece was named after her. Thank you for sharing your meticulous research!