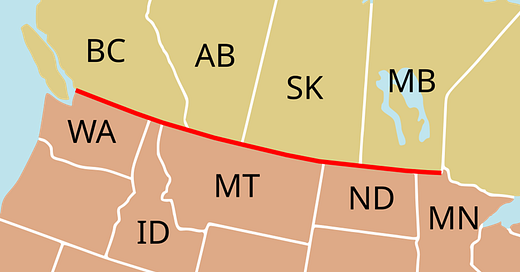

The 49th parallel from Lake of the Woods to the Salish Sea on the Pacific coast marks the boundary between the United States and Canada west from Minnesota.

Since 1783 when the Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War of Independence from Great Britain, the border runs west from the most northwestern point of Lake of the Woods.

With the Treaty of 1818, the two nations agreed to the 49th parallel as the boundary line in their mutual efforts at westward expansion. The British Crown agreed to cede land south of the 49th parallel in what would become the states of Minnesota and North Dakota. The United States agreed to cede land north of the 49th parallel to Canada.

Recently I have found multiple references in my reading to the US-Canada border as the Medicine Line in the 1800s. Indians called the boundary the Medicine Line because when white soldiers and settlers waged war against them they learned when they crossed over an invisible boundary the fighting stopped and peaceful sanctuary could be found.

During the 1800s, Sitting Bull (Lakota), Little Crow (Dakota), and Little Shell (Ojibway) all moved their people across this Medicine Line in order to save the lives of their people from certain death.

By the time my great-grandparents arrived on Lake of the Woods on the Minnesota side of the border in 1903, several of the first settlers in the town of Warroad were Scottish-Métis political refugees from Canada – participants in the Riel rebellion, including Albert Monkman, who fled across the border. Other Scottish-Métis who left Canada for Warroad had worked as translators for the Canadian militia during the rebellion, including Duncan Begg. Begg, readers might recall, had also been a translator for the Warroad School District when it purchased a 4.5 acre parcel of Namaypoke’s allotment in 1905 and earlier had been at the Northwest Angle with Chief Ay Ash Wash when Treaty 3 was signed in 1873.

The US-Canada border divided the descendants of Chief Ay Ash Wash. While his sons Namaypoke and Kakaygeesick and their extended families resided on the American side, members of the Thunder and Lightning branches of the family tree resided across the border at Buffalo Point in Canada.

It wasn’t until 1929 when Canada formally established Buffalo Point First Nation Reserve. It wasn’t until 1979 that a road connected the reserve to the highway.

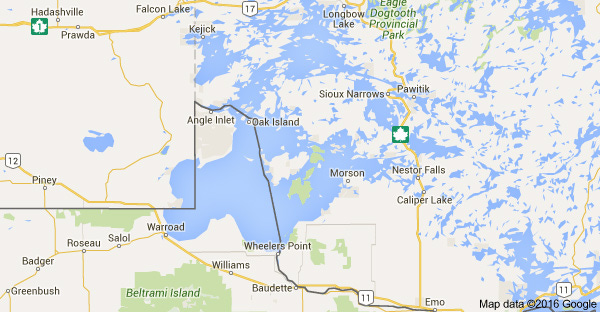

Buffalo Point First Nation is about a 20 minute drive from Warroad. As soon as you cross the border, you turn east to the peninsula which extends into Muskeg Bay. While some have said the name Buffalo Point may be a reference to earlier bison hunting here, others say it is because the parcel on a map looks like a buffalo head. For centuries it has been known among the Ojibway as a spiritual gathering place.

From the shores of Buffalo Point you can look north and see Minnesota. It’s the only place in the Continental US where that is possible.

The US-Canada border splits part of Minnesota off from the rest of the United States. The international boundary cut across Lake of the Woods at a northwest angle to create the “chimney” shape on the Minnesota map. This left a portion of land separated from the rest of the United States by water, Manitoba to the west and Ontario to the north and east.

To reach the Northwest Angle on land, you must cross the border into Canada at the Warroad-Sprague station which is about six miles north of Warroad on Highway 313. The Warroad station, originally built in 1962, was replaced in 2010 with a state-of-the-art facility. The first Border Patrol Station in Warroad was established in 1924 and made responsible for 144 miles of the border line. Thirty-five of those miles are across open water.

After you cross into Manitoba, it is about 60 miles to the Angle Inlet, but it will take you closer to an hour and a half to drive. Not because there will be long lines at the border crossing, but because the pavement eventually ends and a sandy gravel road at a slower speed takes you to the Angle Inlet.

When you arrive at Angle Inlet, you must report your re-entry into the US at an Outlying Area Reporting Station (OARS) located there.

Jim’s Corner, Carlson’s Landing, and Young’s Bay all have these booths where you will find call boxes with two buttons – one for the US to check in on arrival and one for Canada to check out on departure. Video cameras inside and outside in the parking area allow officials to verify your identity and vehicle.

For those who live at Buffalo Point or at the Northwest Angle, for those who own family cabins in the woods or vacation at one of the lake resorts, and for those who travel here for the fishing or hunting — crossing the border is a local custom. High school students from the Northwest Angle and Buffalo Point First Nation are bused to Warroad, which involves four border checks daily.

The Warroad-Sprague Border Patrol Station has a long history with few incidents of note. On Christmas Eve of 1928, Warroad Customs Patrol Officer Robert Lobdell was shot when he arrested someone attempting to illegally enter the United States. It was 1978 — after a half-century of peaceful crossings — when an American named Gregory McMaster hellbent on a murder spree across Canada drove his car through the border crossing. Roseau County Deputy Sheriff Richard Magnuson was shot and killed when he intercepted the vehicle and tried to arrest McMaster, who is still serving out a life sentence behind bars in the US.

During the Vietnam War, there were some young American men who found their way across the border to Canada. Some jumped the train leaving out of Marvin Window factory and others by foot or across the lake.

I’m not sure what to make of news headlines about the threats at the borders or newly imposed tariffs, but I know it doesn’t match the history or local experience along this peaceful section of the US-Canada border.

I am not alone in my concerns about how this affects the lives of those who live along Lake of the Woods who are neighbors, not enemies.

Here along the border, it is the land, the water, the sky which offer lessons of abundance and reciprocity.

“All flourishing is mutual,” Robin Wall Kimmerer in The Serviceberry.

Thank you for this beautiful piece about a border that connects and does not divide. This essay is a reminder of our history, which is parallel and sometimes shared.

Something like 90% of Canadians live within two hours' drive of the American border. The US welcomes 20 million Canadian visits every year-- until this year. The volume of travel cancellations (especially on the part of Québécois, who generally haven't considered themselves Canadian) is surprising. It's unfortunate that the border towns will feel the brunt of this.

Beautiful, Jill. I loved learning about the term Medicine Line, and the way you brought us back to thinking about borders as places where neighbors live side by side. And how the land can teach us everything. Thank you.