If last week’s description of one of my favorite food traditions sent you looking to buy hand-harvested wood-parched wild rice, then you learned it’s mighty expensive and not easy to procure.

But you can also understand why. Not only is it labor-intensive, “wild” wild rice is scarce. Most of it in Minnesota today grows on reservation trust lands.

Lake of the Woods once had vast beds along its shores for hundreds and hundreds of years, long before my great-grandparents arrived to homestead in 1905. When they settled here, they worked so hard to turn forest into farmland.

Until the late nineteenth century, abundant seasonal food resources — game, fish, fowl, berries, maple syrup, and wild rice — provided the people of Kah-bay-kah-nong a diversified and stable economy with a system of self-governance and spiritual leadership. The Ojibway village at the mouth of the Warroad River and the extended community along the western shores north to Buffalo Point had been well-established since at least 1790 when Chief Ay Ash Wash was born.

The 1837, 1854, and 1855 treaties with the US government affirmed the rights of the Chippewa tribes in Minnesota to gather wild rice and other aquatic plants from public waters and, similarly, the rights to hunt and fish on treaty lands.

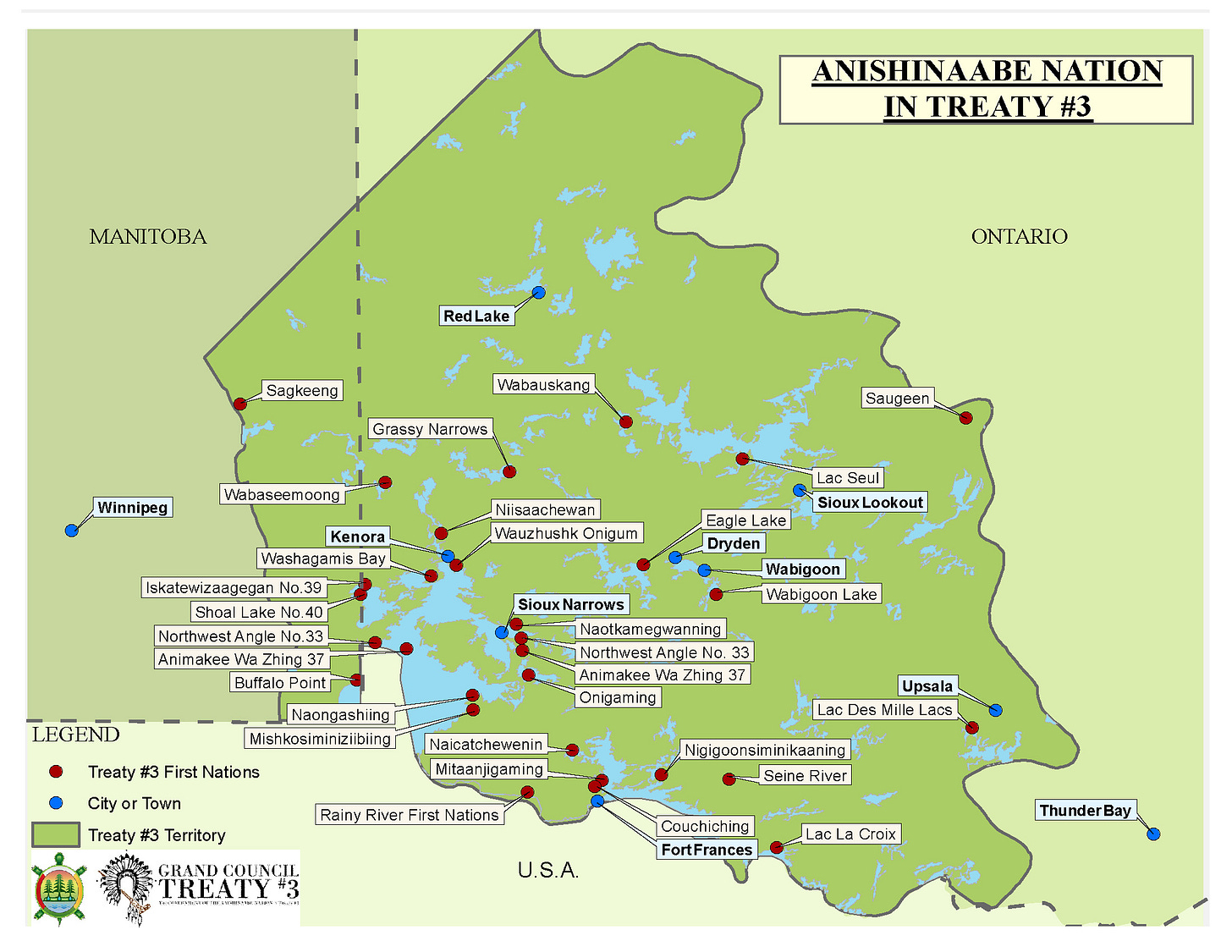

In October of 1873, Chief Ay Ash Wash — great-great-grandfather of Don Kakaygeesick and Henry Boucha — represented the Kah-bay-kah-nong at Treaty 3 negotiations with the Crown of Queen Victoria at Buffalo Point on Lake of the Woods.

Don Kakaygeesick had shown me the ceremonial pipe from Treaty 3 negotiations to explain the significance of what was lost over time. Now I begin to fathom the devastating impact of the treaty on wild rice habitat.

I found a Treaty and Aboriginal Research Report (TARR) issued by Grand Council Treaty #3 from 1995 titled, “Deprived of Part of Their Living”: Colonialism and Nineteenth-Century Flooding of Ojibwa Lands. This passage from their report explains the onset of threats to wild rice habitat on Lake of the Woods.

In 1873, when Treaty No. 3 was signed, the Ojibwa controlled key economic locations in the region, such as fishing stations, rice fields, garden islands, and maple groves…seemed to assure a viable future…The signing of the treaty rapidly led to an influx of Canadian entrepreneurs including contractors for the Canadian Pacific rail line and lumber companies who required water power…Ojibwa shoreline lands quickly became strategic targets for colonial development (J. Lovisek, L.G. Waisberg and T.E. Holtzmann, 1995).

In 1887 at Rat Portage (now called Kenora in Ontario), the Keewatin Lumbering Company with financing from the government built the Rollerway Dam on the north end of Lake of the Woods, raising the water level three feet.

Wild rice grows in shallow waters — from six inches to three feet deep.

The destruction of hundreds of thousands of acres of wild rice habitat led to the deprivation of a primary food source for the local population on Lake of the Woods and pushed villages further inland. Flooding submerged islands, flooded hay fields, drowned and dislocated wild game, destroyed gardens, orchards, homes. People starved.

In 1893 the Norman Dam replaced the Rollerway to produce hydro-electric power to serve industry — sawmills, flour mills, gold mining and eventually timber and paper mills — in the growing city of Kenora, Ontario. Floods eliminated hundreds of thousands of acres more of wild rice habitat with water levels fluctuating as much as 11 feet.

For nearly a century, the timber mills at Fort Francis (Ontario) and International Falls (Minnesota) dumped wastes into the Rainy River which made their way into Lake of the Woods. Eventually, the US Congress passed the Clean Water Act in 1972 and Canada passed similar legislation to cease further industrial contamination of the watershed. But more than fifty years have passed and the toxic algae problem on Lake of the Woods continues to worsen.

Because Lake of the Woods is shaped more like a soup plate than a funnel, the sedimentation and natural healing processes one might expect of a freshwater lake have not occurred. The lakebed is a remnant from Lake Agazziz, a body of water once larger than all of the Great Lakes combined which existed twelve thousand years ago during the Ice Age. Because of Lake of the Woods’ peculiar flat edges with narrow channels as deep as 200 feet, the toxins do not sink to the bottom and become buried in sediment. Instead, they stay along the wide edges of the lake where they are constantly churned up anew, feeding the next algae bloom.

I spent time in the summer of 2022 at the St. Croix Watershed Research Station as an artist-in-residence in Marine-on-St. Croix, Minnesota (where my great-grandparents had first settled after emigrating from Sweden). There I learned a great deal from the research on Lake of the Woods carried out by senior scientists Adam Heathcote and Mark Edlund.

Swimming in Lake of the Woods at the Warroad public beach as a kid, I remember the water would only come up to my knees a hundred yards from shore. The further out I walked, the muckier the bottom got as it turned from beach sand to decomposing matter called muskeg. The word muskeg means bog, swamp or peat. Long before the water would reach my waist, I’d lift my legs up off the squishy lake bottom and kick.

And no matter how hot it was in the sun, the water was always cold. Teeth-chattering cold.

Wild rice requires cold winters. On Lake of the Woods, winters have grown warmer and ice thinner.

Heavier and more rainfalls early in the summer growing season over the past 30 years present new challenges. In June and early July, the first leaves of the plant lay on top of the water. During this stage of growth, it is important for water levels to remain fairly stable. A sudden influx can tug the plant from its thin root system easily.

Research data from 49 lakes in the upper Midwest over three decades — collected by tribal partners — was presented at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco late last year. Madeline Nyblade from the University of Minnesota reported the data shows multiple stressors explain the decline of wild rice, and climate change now exacerbates the threats.

The future of wild rice is in jeopardy.

Nyblade’s research is part of Kawe Gidaa-naanaagadawendaamin Manoomin (First we must consider Manoomin/Psiη), a research collaboration between the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe, the St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin, the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, intertribal organizations, and University of Minnesota scientists codeveloping wild rice research following tribal priorities.

In the state of Minnesota, wild rice may only be harvested with a permit and failure to do so may result in a $1,000 fine from the Department of Natural Resources.

Despite the odds, the native plant Zizania palustris survives along the shores of some remote waterways in northern Minnesota. White Earth, Red Lake, Nett Lake, Mille Lacs, Grand Portage, Bois Forte, Fond du Lac, Lac du Flambeau and other reservation and treaty lands in Minnesota continue to provide stewardship of wild rice habitat.

Every seed a rare and precious thing.

“Every seed a rare and beautiful thing,” so true. Colonialism has many faces not just land theft but soil and water contamination I see. So much to learn here thank you for this interesting intermix of personal experiences, perspective, family history and education on wild rice. I didn’t know it grows in such shallow water. And eww that soggy bottom in Lake of the Woods😞. Such a thread of how the conditions creating wild rice loss impacts us all eventually it seems.

Another excellent article, Jill. The message is just not getting out to the public. Wild rice - the official state grain of Minnesota - is not as lovely as the ladyslipper, as enchanting as the loon, or as comforting as the blueberry muffin, those other honored symbols. Because “wild” rice is easily found in local grocery stores, people don’t realize that an ecosystem and a way of life are under attack, and that our famous lakes are being poisoned. I’m glad you’re doing this work. I hope people listen.