Across the Canadian border to Buffalo Point First Nation

A visit to the museum opened doors to understanding the shared history on Lake of the Woods for the descendants of Chief Ay Ash Wash

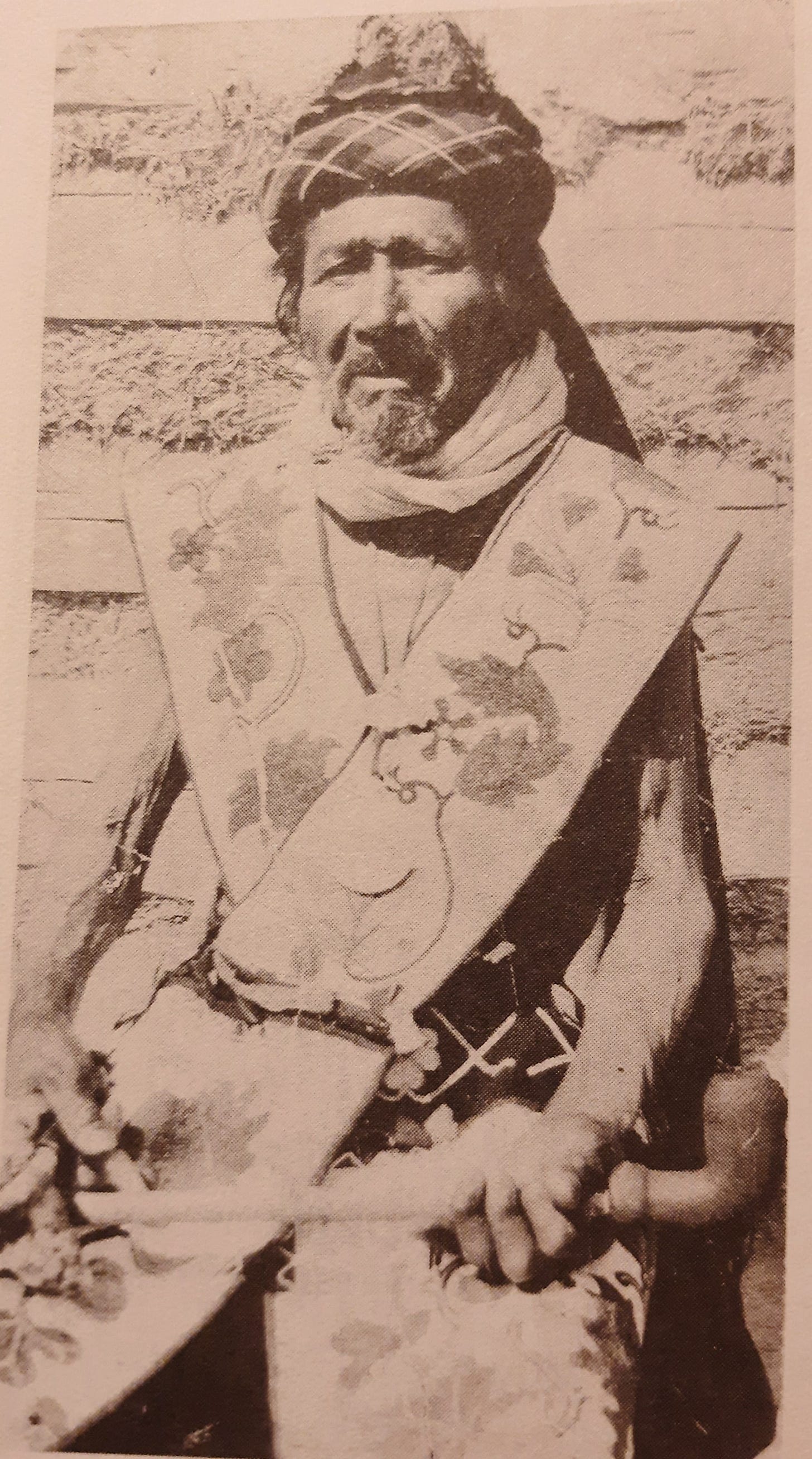

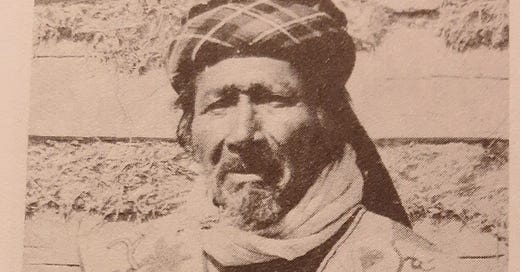

“When they created their border between Canada and the US, they took a knife and split me in two,” Chief Ay Ash Wash (1790-1899) told his children, who told their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

When Don Kakaygeesick heard the story from his great-grandfather, he showed me how Kakaygeesick pretended to stab a hunting knife into his heart and slash it down his torso ripping him in half. This is how Don explained to me the rift created by the Treaty of 1818 which established the border cutting across Lake of the Woods.

Don’s great-grandfather, Kakaygeesick (1844-1968) lived on the American side of the border as did Kakaygeesick’s brother Namaypoke (1840-1916). They both lived with their families near the mouth of the Warroad River where it flows north into Lake of the Woods at the place we know today as Warroad, Minnesota.

On the Canadian side of the border at Buffalo Point lived Chief Ay Ash Wash and his eldest son, Animikeese (1830-1905), also known as Frank Little Thunder. In the Ojibwe language, the word Animikii means thunder or thunderbirds.

I had wanted to learn more about the Thunder branch of Chief Ay Ash Wash’s family tree and last fall I was invited by readers who live at Buffalo Point to visit the museum to further my research.

Buffalo Point First Nation is a 20-minute drive from Warroad, Minnesota, across the Canadian border into Manitoba. It is six miles from Warroad to the Customs and Border Patrol Station, north on Highway 313.

When I visited in October, I was the only vehicle passing in either direction at the station that weekday morning.

An officer asked for my passport. “How long do you plan to stay?” the officer asked.

“I’ll be returning later today,” I replied.

“No luggage? You’re not bringing anything else into Canada?”

“No, sir.” I had my laptop computer and phone on the front seat in plain view.

“And the reason for your visit?”

“Historical research at the museum.”

“Have a nice trip,” he said with a smile and waved me through.

As soon as I crossed over into Manitoba, I took the road east toward the reserve and drove through the woods another ten minutes.

I parked at the Buffalo Point Museum and Government Centre. The shape of the building resembles a tipi. Constructed in 1997, the building was designed to serve several purposes: as a museum, tribal administration office, and emergency shelter.

Murals painted on the exterior walls depicted local flora and fauna. On the front plaza stood a doodem pole with carvings of buffalo and thunderbirds. Two bison statues guarded the entrance.

In the front foyer, there were two enormous carved wooden doors to the interior of the building. On each door, an image of an Animikii, a Thunderbird, clasping a peace pipe.

According to Ojibwe legend, thunderbirds shoot lightning from their eyes and the beating of their wings causes the wind to stir. These mythical birds of prey are symbols of power, protection, and spiritual strength against destructive forces.

Behind the Thunderbird doors, natural light from the circle of windows overhead filled the room. In the center stood the fireplace with its chimney rising up through the roof.

Museum exhibits and cultural artifacts fill the central room. Maps and historical photographs chronicle the people and place across time. Tribal administration offices circle the gallery space.

Chief Ay Ash Wash and Animikeese appeared in the 1880 Census with a total population at Buffalo Point of 44 individuals. In 1884, the population increased to 47.

Today, the number of tribal members residing on the reserve is nearly the same. There are about 130 enrolled tribal members, and about 50 of them live at Buffalo Point. It is one of the smallest First Nations in Canada. Small in terms of number of tribal members and small in terms of number of acres of reserve land.

Canada did not finalize setting aside this land for a reserve and formally recognize Buffalo Point First Nation until 1929. The Canadian government drew the boundaries around their ancestral lands rather than relocate them; similar to the US government with respect to Red Lake Reservation and the allotments for Kakaygeesick and Namaypoke on the American side.

My visit to the museum opened the doors for me to explore further the shared history of the descendants of Chief Ay Ash Wash straddling both sides of the border.

Yet again, I have learned many new things in your writing. I had never heard of a doodem pole, which I falsely assumed was just another spelling of totem pole. When I looked this up I immediately saw there were some profound differences, with the doodems identifying some of the positions in their kinship/clan systems. Of course totem poles are more specific to the Pacific Northwest as well. I would really like to know more about how being born to identify with a particular doodem really influenced the roles people assumed in their respective communities/tribes.

I know it might be out of your way, but my mother and I traveled to the Penbima State Museum in Pembina, North Dakota, near the Canadian border in North Dakota. It had excellent exhibits and information. I found myself making familial ties to people living around Lake Superior while touring this museum. Our visit may have been 10 years ago, so the exhibits and staff may have changed. But the exhibits and Interpretationit was outstanding.