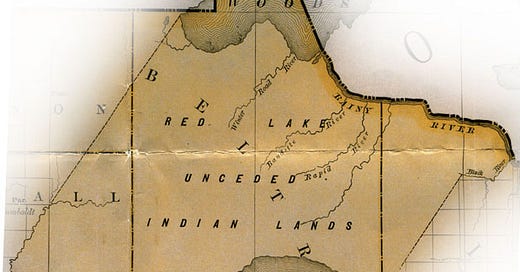

When you look at this 1883 map of unceded Red Lake Reservation land, it may not be obvious there is about a hundred miles between lower Red Lake and Lake of the Woods. The Red Lake tribe historically lived near Red Lake while the Kah-bay-kah-nong lived on Lake of the Woods near the Canadian border.

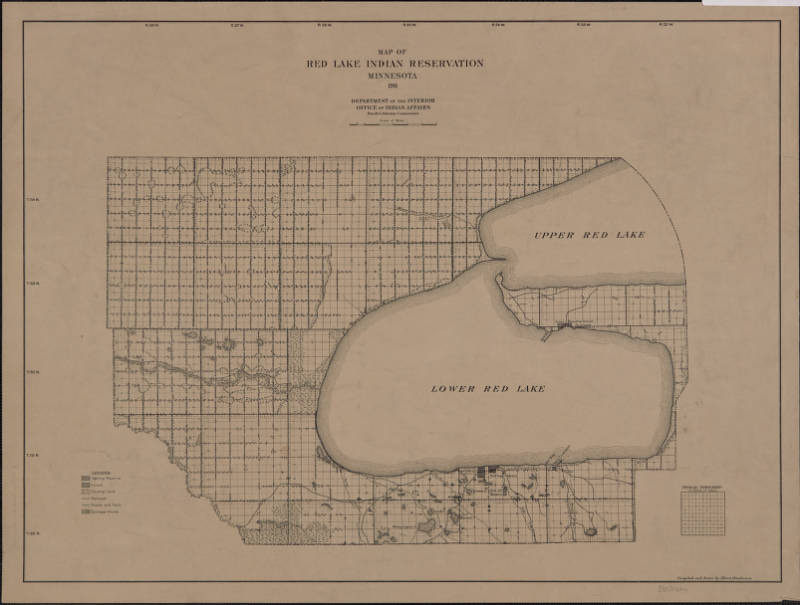

In 1902, Congress agreed to pay the Red Lake tribe $1 million to diminish the reservation lands by a quarter million acres, pushing the boundary south more than 60 miles to Upper Red Lake.

The land north of this new boundary all the way to Lake of the Woods opened to homestead claims.

US Indian Agent and Inspector James McLaughlin negotiated this concession of land in March of 1902 and reported to Congress that 220 of the 334 adult male Red Lake Indians marked an X by their name in agreement. McLaughlin is perhaps best known for having been the Indian Agent responsible for the arrest of Sitting Bull in 1890, which led to the chief’s death and the Wounded Knee massacre.

There is nothing in this original 1902 agreement ratified by Congress which addresses Red Lake Indians residing on land in the city of Warroad nor is there any mention of reserving any lands for Namaypoke or his brothers at Lake of the Woods. It simply legitimated claims by squatters who had encroached on unceded Red Lake Indian land.

Preemptory filings, or squatters claims, at the Crookston Land Office on lands in the village of Warroad had begun in October of 1898 when Charles Moody became the first to file at the Crookston Land Patent Office.

Moody and other early settlers published notices in The Plaindealer or The Roseau County Times of their intent to file homestead claims on specific surveyed land parcels in the village of Warroad.

Acreage designated by the Warroad Townsite Company for Namaypoke and Kakaygeesick could not be sold until a Warranty of Deed could be obtained on their Indian land. So it was interesting to learn earlier this month from the documents sent by the great-grandson of Namaypoke, Roy Jones, that these allotments were not approved until the Warroad School District petitioned the Secretary of Interior in 1905 for permission to purchase a parcel of Namaypoke’s land allotment for the purposes of a new school for settlers’ children.

What I couldn’t quite wrap my head around is what else I discovered in these new-to-me documents. I had not known that in 1903 Namaypoke had revised his 1897 allotment application.

Dated January 17, 1903, this document is so confusing, I quote it in full:

Hon. Sylvester Peterson, Register U.S. Land Office, Crookston, Minnesota

Sir:

In compliance with your letter No. 5452 of December 22, 1902 and the Hon. Commissioner’s letter before of December 16, 1902, relative to my Indian Allotment Application, No. 2, for Lots 1 & 2 and the S ½ of NW ¼, Sec. 29, T. 163 N., R 36 W., made December 5, 1897. I hereby elect to relinquish and drop your said Indian Allotment No. 2, the SW ¼ of NW ¼, Sec. 29, T. 163 N., R 36 W., and elect to hold Lots 1 & 2 and the SE ¼ of the NW ¼ Sec. 29. N. 163, R. 36 N, as my Indian Allotment.

Very respectfully,

Na May Pock [his X mark]

Witnesses: Albert Berg and Duncan F. Begg

Notary: Chas. A. Moody

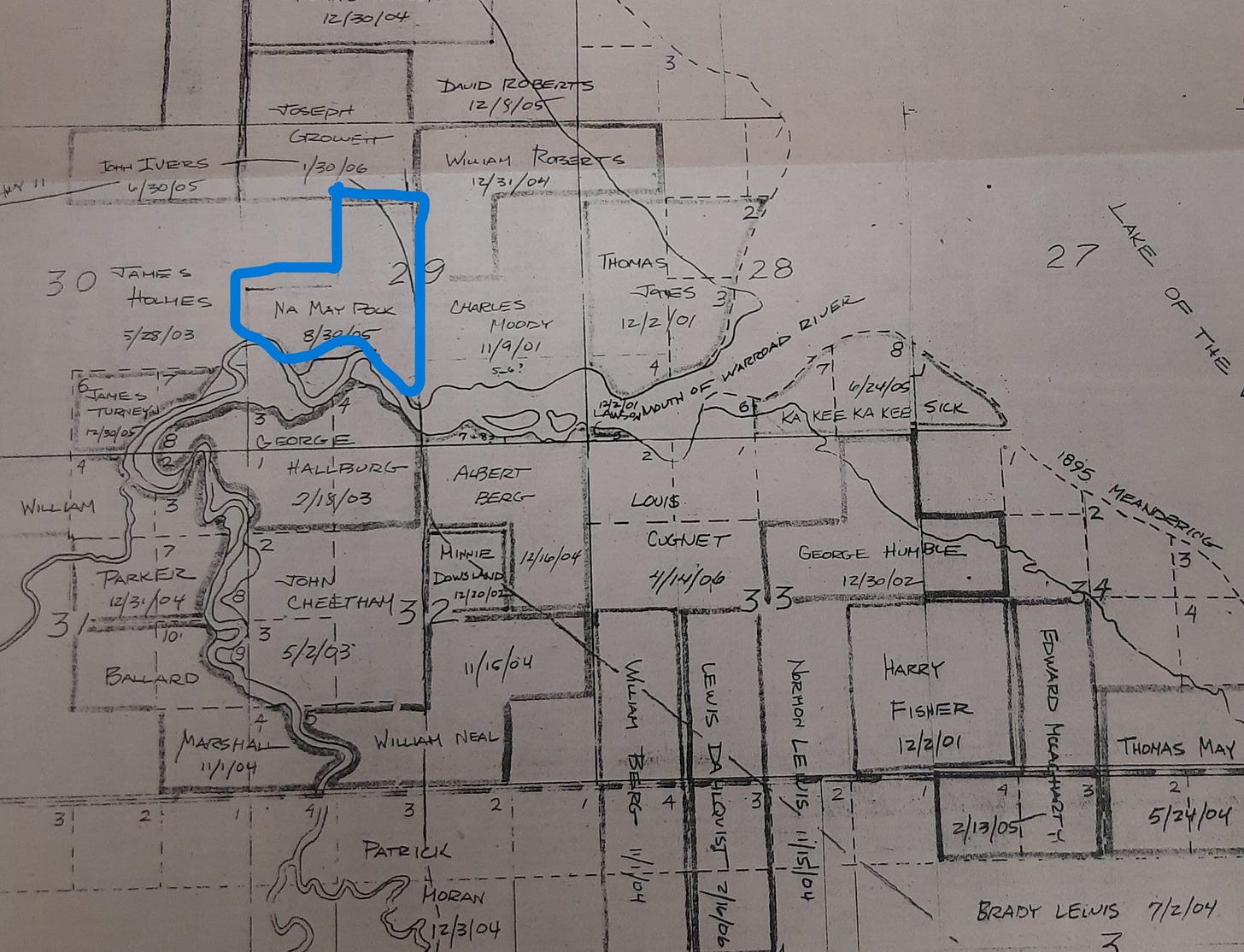

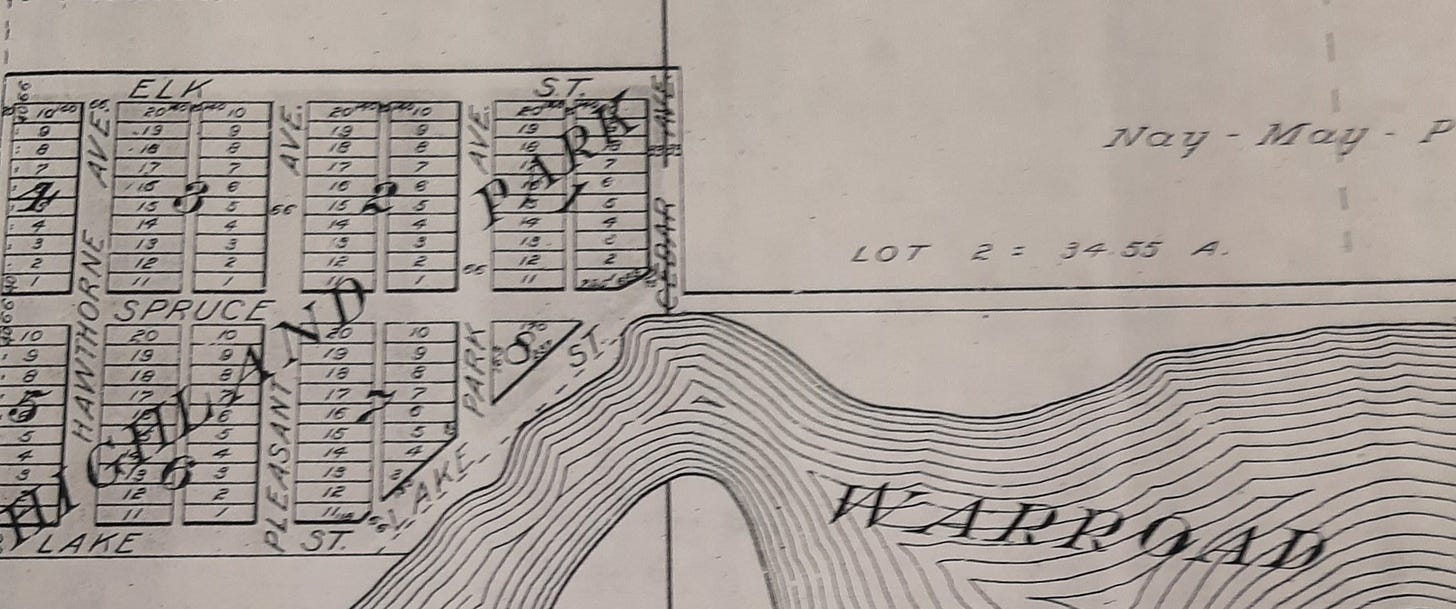

I found this difficult to read and too complex to understand without looking at a map. I have to wonder what Namaypoke made of this document when he signed with his X mark.

What changed between 1897 and January of 1903? The opening of Red Lake reserved lands for homestead claims.

What changed in Namaypoke’s application for allotment? Notice S 1/2 — the southern half — is reduced to SE 1/4 — the southeastern quarter. The allotment shrank an estimated 40 acres when Namaypoke marked his X next to his signature, relinquishing the SW 1/4 — southwestern quarter — and electing to hold only SE 1/4 — the southeast quarter.

My eyes have gone back and forth hundreds of times between the affadavit and the Warroad plat map from 1906.

I have outlined in blue the area of Namaypoke’s amended allotment. On this 1906 map, that missing square in the upper left is included with the property claimed by James Holmes. Note the date next to Holmes’ name appears to be four months after Namaypoke amended his application to relinquish that corner piece.

Who was James Holmes? Why am I not surprised to learn in the archives at the Warroad Heritage Center that he was the Assistant County Auditor, serving under Charles A. Moody, and one of the most prosperous business men in Warroad at the turn of the twentieth century.

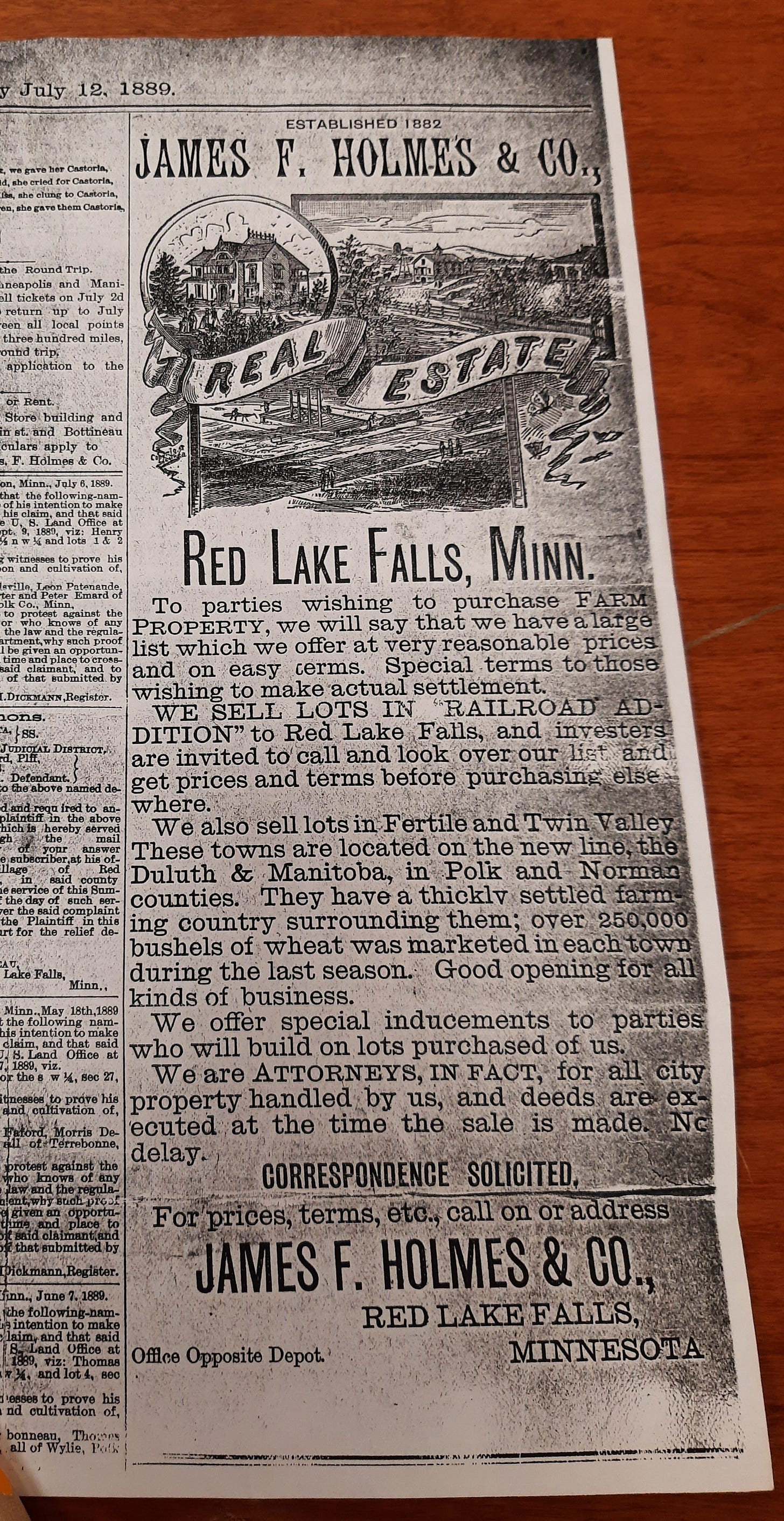

Born in St. Paul in 1828, James Friend Holmes conducted various business ventures in his long career, including his position as agent of the Minneapolis Brewing Company, loan agent, insurance agent, real estate agent and gentleman farmer. An advertisement in the Grand Forks newspaper in 1899 notes his real estate company in Red Lake Falls, Minnesota, had been established in 1882.

Holmes first arrived in Roseau County the first week of October 1895. As an agent of Bankers Life Insurance, Holmes registered as a guest at the Hotel Roseau for a week. Four months after his visit to Roseau, he received a commission from newly elected Governor Clough, who appointed him Notary Public in Roseau County. Clerk of Courts Iver Torfin appointed Holmes his deputy clerk in early 1897.1

When Charles Moody and others moved to Warroad from Roseau in 1897, Holmes already lived in a log house along the wooded bend in the river. He was described in the Roseau County Times in October of 1897 as “a small man with a big voice” and the “only Democrat in the whole town.”

In April of 1900, James Holmes published a public notice in The Plaindealer of his squatters claim and did so again in 1901. But when the reservation lands opened to homestead claims in 1902, the US Land Patent Office in Crookston, Minnesota found two competing claims for the same land.

W.B. York had been squatting along the same wooded bend in the Warroad River as Holmes. York was among the first white settlers in Warroad. Born in Maine in 1848, he came to Minnesota in 1866. Mr. York and his family were living in Badger by 1887 where he served as the first postmaster. When the family moved to Warroad in 1893, York was a fish hauler, transporting fresh-caught fish as far west at Grafton, North Dakota, then returning to Warroad with supplies.

It was W. B. York and his son Lute who built the first log schoolhouse in Warroad in the late summer of 1897. And in January of 1900, W.B. York engaged a work crew stringing ties on the grade from the river north towards the border for the new Canadian Northern railroad. That same month Lute and his father built the Warroad jailhouse.

By April of 1900, W.B. York officially relinquished his homestead claim to Holmes. York’s son Lute filed a homestead claim in Roosevelt, twelve miles southeast of Warroad. W.B. York’s wife had died and he moved to Alberta where he worked for Canadian Northern Railway. When W.B. York was hauling lumber near Wataskawin, Alberta, a team of horses with a wagon full of logs ran over and crushed him to death in May of 1906.

In February of 1906, Holmes married Miss Mollie Hassenstab, who had arrived from southern Minnesota with her father to homestead.

It was Holmes who created Highland Park when he subdivided some of his land into city lots near the Warroad River. Note it is adjacent to Namaypoke’s allotment.

Holmes bought additional lots downtown and constructed two office buildings. When his son was born, the newspaper claimed the boy a future president. Holmes held various public positions: notary, justice of the peace, deputy clerk of court, village recorder, county assessor, and in 1914 he became postmaster in Warroad and drew an annual salary of $1,400. Holmes retired to Young America, Minnesota, where at the age of 99 he sat on his porch smoking his pipe when he suddenly dropped dead.

It strikes me that it was only after I received copies of documents from Roy Jones that I could piece together more of this puzzle about what happened to his great-grandfather’s land. Without the amended allotment application, the records publicly available told a story about two white men competing for the same land without acknowledging whose land they laid claim to.

And stay tuned! Roy Jones sent me another batch of documents which will further explain what happened to the rest of Namaypoke’s allotted land since 1905.

File folders of newspaper clippings, photographs, public documents and related research materials on the families of Holmes and York at the Warroad Heritage Center archives provided historical information not otherwise directly attributed in this report.

Wow this is some serious digging and integrating and writing. This struck me "I have to wonder what Namaypoke made of this document when he signed with his X mark." And can't wait to learn what is revealed in the docs Roy Jones sent.

It is a lot to take in. I can't imagine how hard it was for you to wade through all this information--and I'm glad you have helpers with old papers. It's important to see how squatters made their claims seemingly legal since it happened all over the country. I also noted that a jail was one of the early buildings and wondered who ended up in that jail. I can imagine there were big struggles over land rights. Thanks for your deep research into the history of this part of the world.