To understand how Kakaygeesick’s land belonged to Red Lake, but he did not, required me to learn more about tribal membership.

It’s confusing and complicated because every federally recognized tribe is different. Different in membership criteria and different in their enrollment process. Different, too, in the specific rights and privileges of political citizenship extended to members.

What I hadn’t fully appreciated is how many in this country find themselves without official tribal membership like the descendants of Kakaygeesick and Namaypoke.

There are almost 10 million people in the United States who identify as American Indians but only two million who are enrolled in federally recognized tribes, according to the most recent Census data.

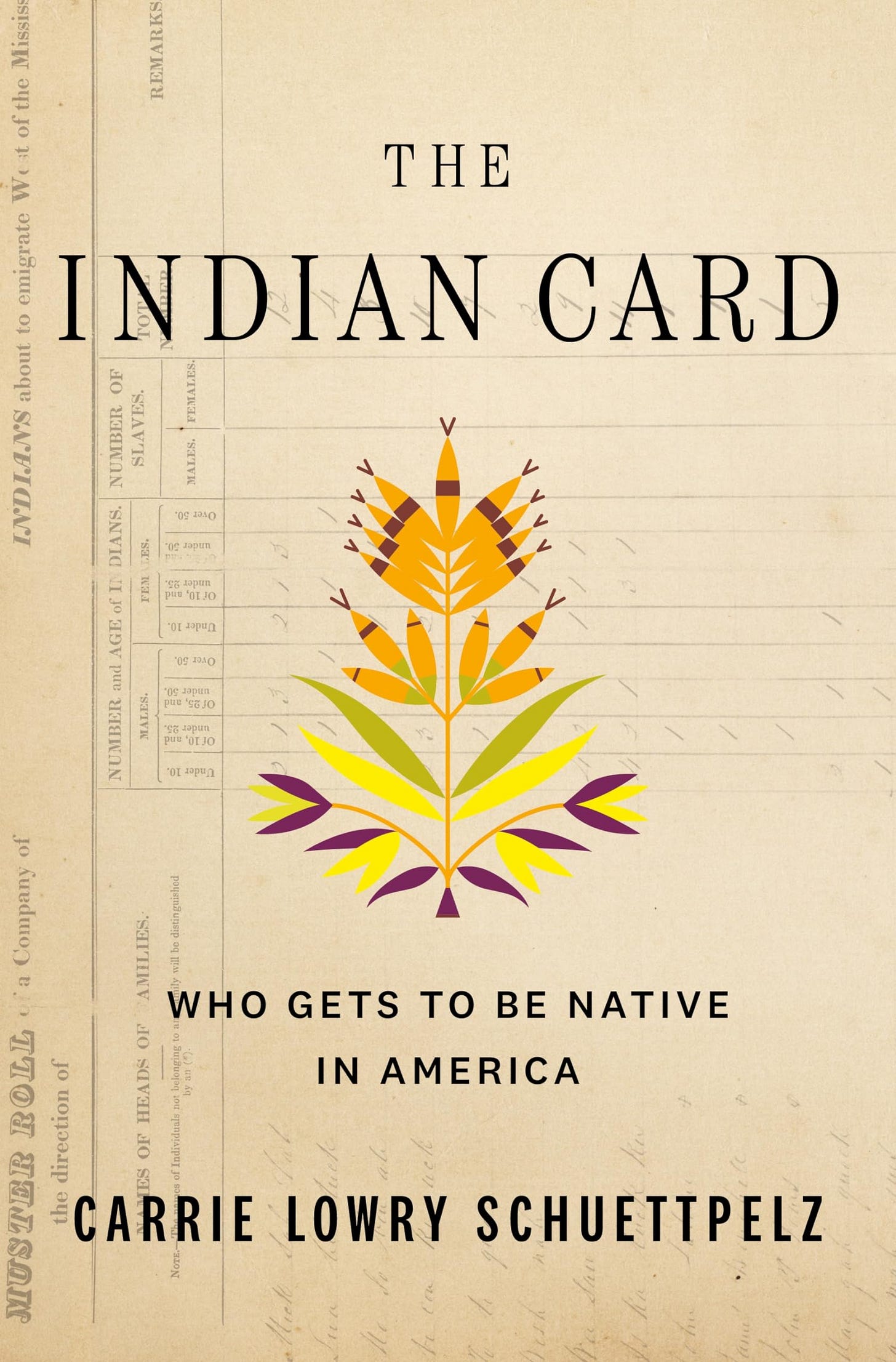

In a new book, The Indian Card: Who Gets to Be Native in America (Flatiron Books, 2024), Carrie Lowry Schuettpelz1 investigated the reasons why this gap exists, why it keeps growing wider, and what it means for the future.

Birth rates don’t account for the growing numbers.

Nor do the technical changes in the way the US Census categorizes, collects, and counts this demographic data. Since 2000, the ability to check multiple racial/ethnic categories adds to the complexity of data analysis, but it doesn’t account for the widening gap.

Why the gap exists and grows has to do with the history of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

In March of 1824, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun established the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) under the War Department, making it one of the oldest federal agencies in the United States.

In 1849 the Department of Interior was created to advance westward expansion into the interior of the continent and the Bureau of Indian Affairs moved from the War Department to the jurisdiction of the Secretary of the Interior.

Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Act in 1851, authorizing the creation of Indian reservations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs appointed Superintendents and Agents to carry out the federal government’s policies of removal and relocation.

This growing federal bureaucracy required documentation of membership rolls in order to pay annuities on ceded tribal lands. These documents recorded Indian status based on blood quantum.

Blood quantum as it applied to Indians became federal policy—a policy based on the pseudoscience of eugenics—a passive form of genocide. Indians would literally breed themselves out of existence and rid the federal government of “the Indian problem.”

Beginning in 1885, the Bureau of Indian Affairs required its agents to submit an Indian Census of each reservation every year. When the Allotment Act passed in 1887, tribal membership rolls were created along with land indexes. If an indvidual Indian received a land allotment, then they would not receive any annuity payments — annual compensation payments from the federal government for ceded lands disbursed to tribal members.

Because he received an allotment of Red Lake Reservation land, Kakaygeesick — like his brother Namaypoke — did not receive annuity payments. The right to annuity payments is granted with enrollment in the Red Lake tribe.

In the 2011 final summary judgment of Kakaygeesick v. Salazar, reference is made to the passage below. It is from a preliminary hearing which determined Don Kakaygeesick and his siblings ineligible for the inheritance of his great-grandfather’s allotment based on blood quantum requirements.

It appears that you and the other appellants are claiming eligibility through a Chief Ay-Ash-A-Wash, and his son, Little Thunder. The records show that Nay-May-Puck, son of Ay-Ash-A-Wash was allotted land on the ceded portion of the Red Lake reservation under the Act of May 27, 1902. The Act permitted the Indians to retain lands on which they resided and improved instead of moving them to the diminished Red Lake Reservation. The Act, however, contains no provisions reserving or extending Red Lake membership rights to these Indians or to their descendants. The documentation furnished does not prove that you or the other appellants possess any Pembina Chippewa blood. As outlined above, an individual must possess at least ¼ degree Pembina Chippewa blood. You and the other appellants may possess Indian blood, however, only Pembina Chippewa blood can be considered for this award.

What troubles me is the use of blood quantum to deny descendants their inheritance from a blood relative.

After reading The Indian Card I now see how blood quantum is a double-edged sword. With one edge of the blade, those who do not meet the requirements for tribal enrollment are ineligible for services provided through the Bureau of Indian Affairs including health care, housing, higher education, employment, etc.

The other edge of the blade cuts off the future for tribal nations. Numbers steadily decline in terms of future enrolled members. Extinction of American Indians is the consequence deliberately built into a 200-year-old federal bureaucracy.

More than half of federally recognized tribes in the United States still use blood quantum membership requirements. Red Lake Nation is not exceptional in this respect.

The Constitution of Red Lake Nation requires 1/4 blood quantum for tribal members. And that blood quantum must come from Red Lake tribal members. It doesn’t take seven generations to extinguish a bloodline. Especially with intertribal and interracial marriages.

In 2019, Red Lake Nation amended their constitution and revised their membership rolls in regards to blood quantum to sustain the size of their population. Enrolled tribal members born before 1958 were all reclassified as 4/4.

But recalculations of blood quantum for tribal members may not be sufficient to stop the decline in numbers, according to population projections conducted by the Wilder Foundation for Red Lake Nation in 2022. If the 1/4 Red Lake blood quantum requirement is not changed, the size of the tribal population may drop from 16,000 to 1,000 members in a century.

Blood quantum is one reason, but not the only reason for the disenfranchisement of millions of Native Americans from tribal nations, according to The Indian Card.

Factual errors in the historical records of this federal bureaucracy and the incredible number of lost or destroyed documents complicate tribal enrollment procedures.

Removing Indian children from their families, forbidding the use of Native languages, criminalizing religious customs, denying their right to exist with practices that included the forced sterilization of women — policies continued into the 1970s — severed family and tribal connections.

The Indian Card put into a larger context the wide array of circumstances in which people lack tribal membership in a federally recognized tribe. The descendants of Kakaygeesick and Namaypoke fall into this widening gap.

Carrie Lowry Schuettpelz is an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. She holds an MFA in creative writing from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a Master in Public Policy from Harvard’’s Kennedy School of Government.

I have just a little bit of knowledge about blood quantum, but I've wondered about it often. Specifically, I wonder about the difficult decisions it places before enrolled young people--do you prioritize your heart when looking for someone to have children with or do you prioritize the endurance of your community? That would feel like an impossible choice to me. Thanks for the book recommendation.

Wow I didn’t realize the impact and consequences of blood quantum. “Passive genocide” is good overall descriptor for so many pernicious laws and policies that had unforeseen consequences. A lot to reflect on here.