Kakaygeesick wanted his family to have his land when he died

and he worried it would be taken from them

Even though I have spent years doing research on Kakaygeesick and the history of Warroad, it wasn’t until I tracked what happened to the allotment issued to his brother Namaypoke that I began to really comprehend how the loss of land had loomed over Kakaygeesick his entire life.

Kakaygeesick was 16 years old when Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States. When Kakaygeesick died in December of 1968, Richard Nixon had just won election to the White House.

It is difficult to wrap my head around how much the United States changed during his lifetime, while also recognizing how much Kakaygeesick tried to keep his language, cultural practices, and spiritual traditions alive.

The land where he was born and the lake on which he lived sustained his way of life.

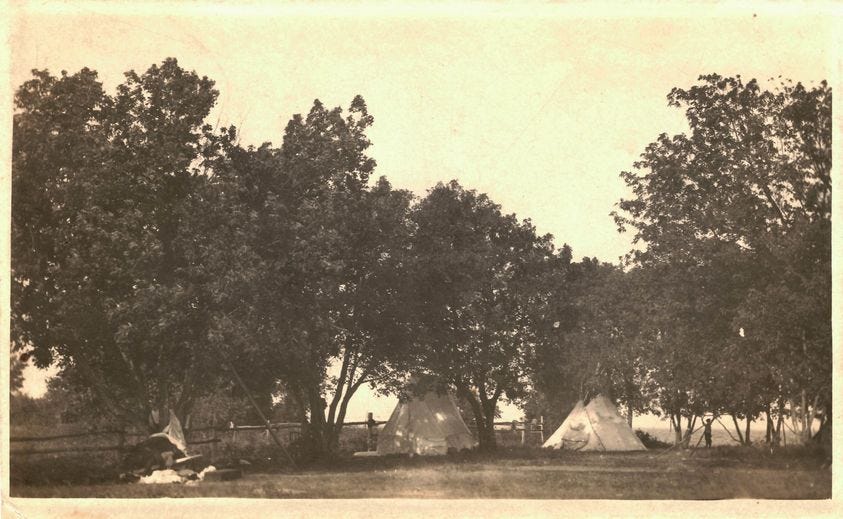

Long before the federal government put Kakaygeesick’s name on allotment papers, Kakaygeesick had made his home southeast of the mouth of the Warroad River along the shore of Lake of the Woods.

His brother, Naymaypoke (1840-1916), lived across the river and close to the main road, about two miles away on foot. Both men were sons of Ay Ash Wash (1790-1899), chief of the Kah-bay-kah-nong.

In 1905, the United States government issued Kakaygeesick and Namaypoke allotment papers for acreage on which they had resided long before white settlers arrived to claim land in their Ojibway village.

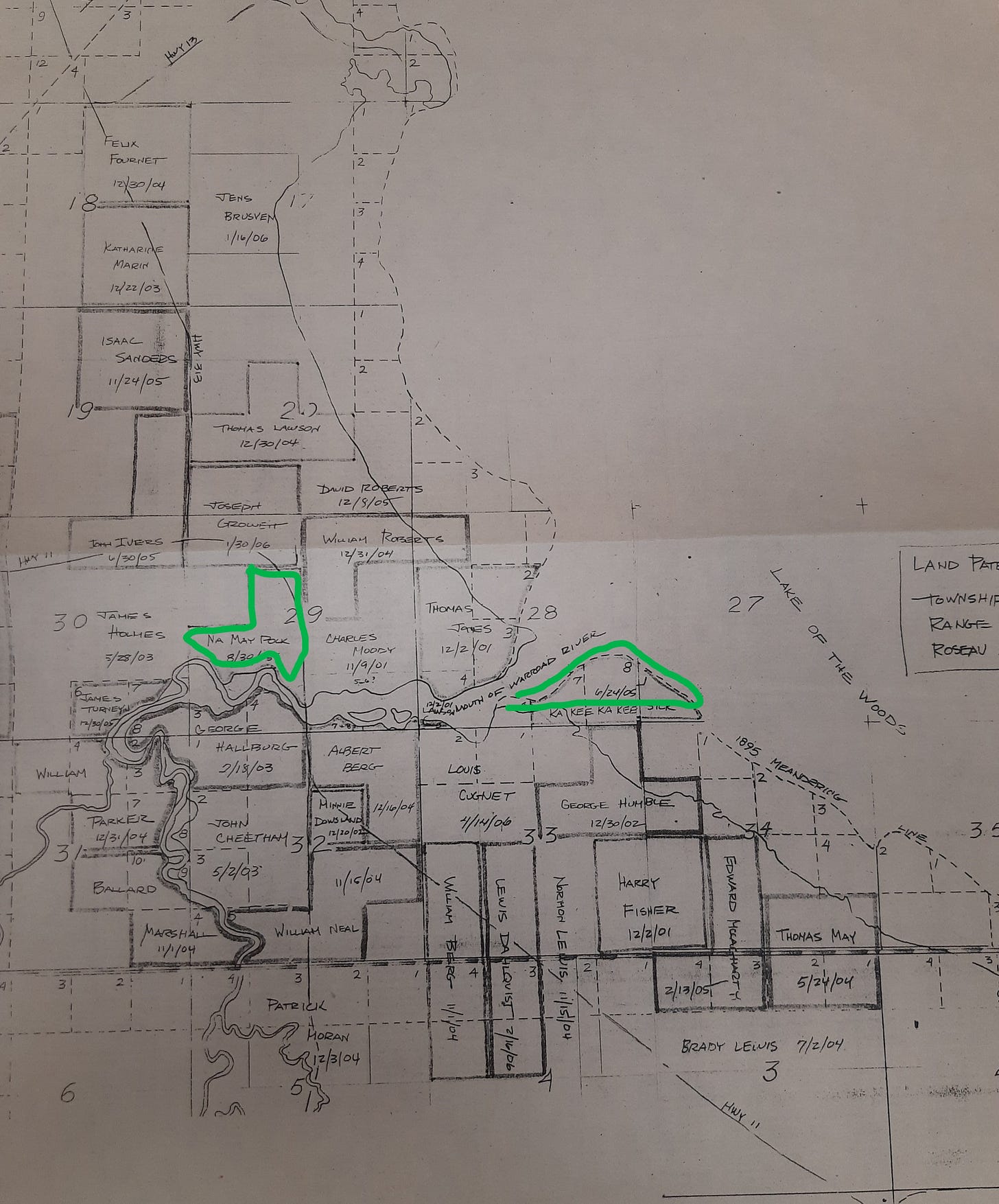

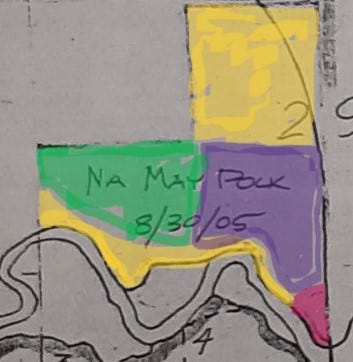

The 1905 plat map of the City of Warroad below outlines the two allotments in green.

In recent months, I have followed the paper trail of Namaypoke’s allotment from the submission of his application in 1897 to the final sale of parcels in 1955.

Namaypoke and Kakaygeesick had both witnessed the encroachment of squatters and land speculators in their Objiway village, the rush of homesteaders to claim land, a fur trading post turn into a city, the arrival of commercial fishing, and transcontinental rail service by the early twentieth century.

Kakaygeesick had also seen what happened to the land in Naymaypoke’s allotment. Before the papers even arrived in 1905 from Washington, DC, the Warroad School District had paid Namaypoke $150 for a 4.5 acre parcel. Squatters built homes and even businesses set up operations on his land. The railroad had already taken an easement in 1901. When the Indian Agent at Red Lake sold two parcels of Namaypoke’s allotment in 1914, he first had him declared non-competent, then helped the Warroad Townsite Company clear titles to lots of his land they had already sold to settlers. After Namaypoke died, the state highway nibbled away a few more acres from his estate.

Kakaygeesick must have known that in 1955, Red Lake Reservation approved the sale of the last two parcels of his brother’s allotment and sold one quarter section to Marvin Cedar & Lumber Company. Kakaygeesick also knew that when Namaypoke’s grandson Max Jones made an offer at the same time in 1955 to purchase the other parcel — the seven acres along the river where his grandfather was buried — he was outbid. The Indian Agent sold it and then paid Max his share of Namaypoke’s inheritance — an amount less than half what Max had offered to pay in cash to keep the property in the family. In 1961, Kakaygeesick saw that seven acres where his brother was buried sold again and subdivided into private residential lots.

Kakaygeesick had reason to worry about what would happen after his death to his land and his family by the 1960s. It was no secret Kakaygeesick feared his heirs would be dispossessed of his allotment.

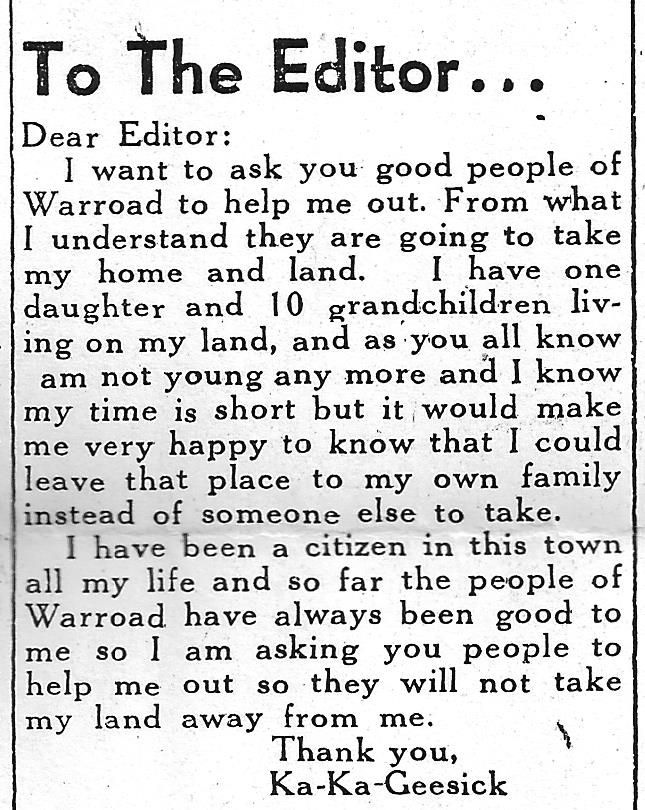

On July 11, 1962, The Warroad Pioneer published a Letter to the Editor in which he made his concerns a matter of public record.

I found no records of how the good people of Warroad responded to Kakaygeesick’s request. And I found no evidence city officials took any action in this regard either before or after Kakaygeesick’s death in December of 1968.

No official actions taken resulted in the family members who were living on the land when Kakaygeesick died continuing to reside there. His widowed daughter, Mary Angus, lived there with her son, George. His widowed daughter-in-law, Verna Kakaygeesick, lived there with her son, Robert, and his wife, Florence, and their children.

Don was one of the children who had been living there as a young boy on his great-grandfather’s allotment in the early 1960s. Forty years later, Don and his siblings cared for their elderly mother, Florence, on Kakaygeesick’s land.

When I first read Kakaygeesick’s letter to the editor from July of 1962, I began to understand how Don Kakaygeesick felt when he was forced to move off his great-grandfather’s allotment in 2012. What Kakaygeesick had tried to prevent a half-century earlier from happening, happened anyway.

But that is a much longer story for another day.

How old was Kayakgeesick when he died? If he was 16 when Lincoln was elected in 1860, he would have been born in 1844 according to my math. Was he 124 years old when he died? Seems unlikely for the times............Just wondering!

I’m hooked and am eager for more writing on that later date! Thank you for sharing your work.