Falling through the cracks of Red Lake's political history

the descendants of Namaypoke and Kakaygeesick were - and then were not - tribal members

Another package of documents arrived on my doorstep this week.

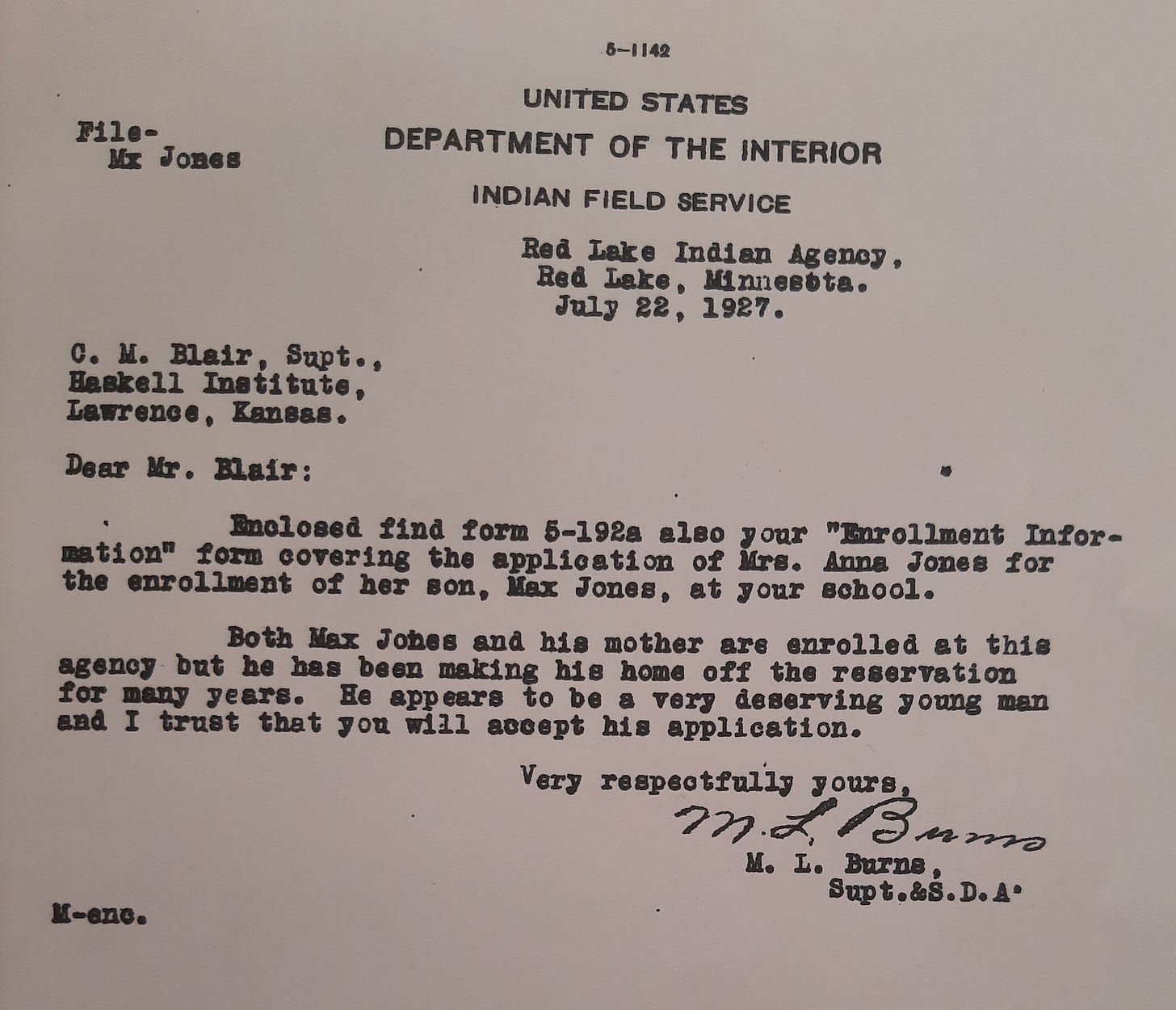

Roy Jones, the great-grandson of Namaypoke, sent copies of correspondence regarding his father, Max Jones.

One letter stood out.

M.L. Burns, the Superintendent and Senior Disbursing Agent for the Red Lake Indian Agency, wrote on July 22, 1927, to C.M. Blair, Superintendent of the Haskell Institute, in Lawrence, Kansas, regarding the admission of Max Jones.

This letter verified tribal status in the second paragraph. “Both Max Jones and his mother [Anna Namaypoke Jones] are enrolled at this agency but he has been making his home off the reservation for many years.”

It is also one more piece of evidence that Namaypoke’s family had been Red Lake tribal members before 1936. Last week, I showed the entries in the 1929 Red Lake Indian Census where Max’s mother, Anna Namaypoke Jones, and his sister, Sally Jones, were recorded as enrolled members. Max had not appeared in that Census because he attended Haskell in 1929.

How could the descendants of Kakaygeesick and Namaypoke be Red Lake Indians in the 1920s but not after 1936? What changed at Red Lake Reservation during this period?

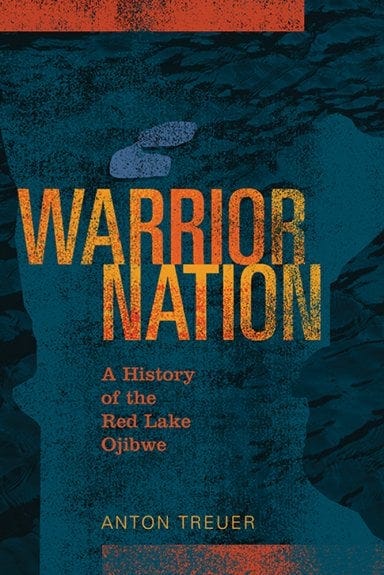

Anton Treuer’s Warrior Nation: A History of the Red Lake Ojibwe (2015) helped me identify two major turning points that offer context for how and why this might have happened.

The first turning point came in 1918 with the charter of a constitution and the creation of Red Lake General Council.

The second came after the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act and involved a lawsuit filed by Red Lake against the Office of Indian Affairs and the other Minnesota Chippewa tribes for mismanagement of trust funds. That lawsuit led to a 1935 Supreme Court decision which affirmed the independence of Red Lake Nation and exclusive rights to their lands.

Between these two turning points in Red Lake’s political history, there was a transition away from the US government agency model run by white Indian Agents.

Until 1918, Indian Agents had sole authority to negotiate real estate transactions and timber sales on reservation lands and a monopoly on retail trade at the agency. Agents had long functioned as police officers, bankers, judges, postmasters, business managers, and the only merchant on the reservation. They had undermined the chiefs, usurping many of their political powers and spiritual authority.

In 1918, Article 1 of the constitution made the seven hereditary chiefs the political agents of Red Lake Nation. This reasserted the legitimacy of their traditional ways of self-governance. It also became a charter document to guide the US government in its relations with a more autonomous Red Lake Nation.

Article 2 created the General Council with five delegates from each of the seven hereditary chiefs. They constituted the members of the council. And this voting body became the way to effectively change the role of white Indian Agents in administrative matters (Treuer, 2015: 196-197). Particularly in its financial affairs.

The US government had collected $8 million from timber sales on the 3 million acres of Red Lake Reservation land recently ceded. Those revenues were lumped together with the trust funds for all Minnesota Chippewa Indians by the US government.

By 1918, Red Lake generated 80 percent of the revenue from sales of land and timber on Indian land in Minnesota but collected only 14 percent of profits from trust funds (Treuer, 2015:195). In short, the US government took the profits from timber sales on Red Land Reservation lands to pay what they still owed for land previously taken from the other Chippewa tribes in Minnesota. Why should Red Lake Indians pay the debt the United States owed to the rest of the Minnesota Chippewa for the loss of their lands?

In response, the creation of the constitution and council provided Red Lake Nation with the political instruments to remain independent and demand fair and direct compensation. And the historical record shows, it mostly worked.

But no one from Warroad had been invited to the meeting in 1918 to establish the General Council. According to historian Anton Treuer, “Chiefs from villages outside the diminished reservation at Warroad and other places were not formally recognized in the new structure” (Treuer, 196).

While Namaypoke and Kakaygeesick did not have representation on Red Lake General Council, that did not necessarily exclude them from tribal membership. There were other Ojibway Indians across Lower Red Lake at Ponemah whose chiefs also had not been included in the 1918 meeting, but they were considered members of the Red Lake Band. Plenty of Ojibway people, Treuer noted, had moved to Red Lake Reservation since 1889 and changed their tribal associations to avoid relocation to other reservations.

Before 1918, Anton Treuer wrote, “[Y]ou didn’t have to be born in Red Lake to be a Red Laker; but you did have to live there” (2015:199). Residency on Red Lake Reservation land qualified Indians for enrollment at the agency during this period. One might be from Leech Lake, Cass Lake, or the Fond du Lac band and it didn’t matter back then as long as one were a resident.

This first turning point in Red Lake’s political history helped me understand why enrollment of the adult children and grandchildren of Namaypoke and Kakaygeesick may have been approved in the 1920s. Red Lake Nation advanced its political and economic interests with their strength in numbers.

Most other tribes did not develop a modern governance structure until after Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed this bipartisan legislation which became known as the “Indian New Deal.” It was an effort to decrease federal control over American Indians and increase the responsibilities of Indians to govern themselves.

But such effforts began in 1918 in Red Lake and the tribe had pursued litigation against the US government for mismanagement of trust funds for more than a decade. In a decision on October 14, 1935, the Supreme Court affirmed Red Lake Nation’s independent status for trust fund administration and reaffirmed their exclusive right to ownership of its lands. This further solidified the sovereignty of the tribal nation.

Red Lake General Council then passed a constitutional amendment sometime in the mid-1930s which required tribal members to be born to Red Lake parents. If your parents lived off the diminished reservation, you did not qualify for Red Lake tribal membership.

I suspect the 1936 denial of membership based on assertions about the geographic origin of Namaypoke and Kakaygeesick came after this constitutional amendment passed and during the transfer of documentary and fiduciary responsibilities of the Indian Agency to the jurisdiction of Red Lake General Council.

Between 1918 and 1936, Red Lake General Council struggled to find a way between the constraints of US governmental bureaucracy and the demands for independence and economic and political sovereignty. In the process, it appears the family members in Warroad fell through the cracks as the old agency system crumbled while a new administrative and governance system was under construction.

I like the clarity you provide to explain your point and how this was even possible. I find myself shaking my head in disbelief at the lengths people will go to remain in power...

What great research and a clear line of reasoning, cause and effect, you’ve laid out. I’m glad you’re getting those outside documents to help unravel this important and historically relevant story.