In the Warroad school board minutes, I had discovered Mr. Begg accompanied Naymaypoke to the State Bank of Warroad on the morning of March 23, 1905.

Begg translated for the school district, which paid Naymaypoke $150 for the title to his land. The school board minutes from 1904 had indicated Mr. D. F. Begg had been hired to tend the school building and grounds. Who was Mr. Begg?

Reading through the original records of the school district photographed by my sister, Barb, from the archives at Minnesota History Center, I am surprised to see the name Begg in the 1909 school attendance records.

Edith Begg enrolled in first grade at seven years of age and her father is listed as “William Begg, Norwegian and Scottish, Laborer.” What family relationship did her father have to “Dreveau F. Begg”?

I found the obituary online of William Begg’s eldest son, Julius, a US veteran of WWI, at the Kenora Great War Project. I discovered “Dreveau” is my mistake in transcribing the penmanship in the school board minutes.

Duncan not Dreveau. William Begg’s father — grandfather to Edith Begg — was named Duncan Finlayson Begg. He had been born in 1845 on Lake Superior in Michipicoten, a trading post. The Hudson Bay Company had recruited his father in Scotland in 1831 to work as a blacksmith. His mother was Cree.

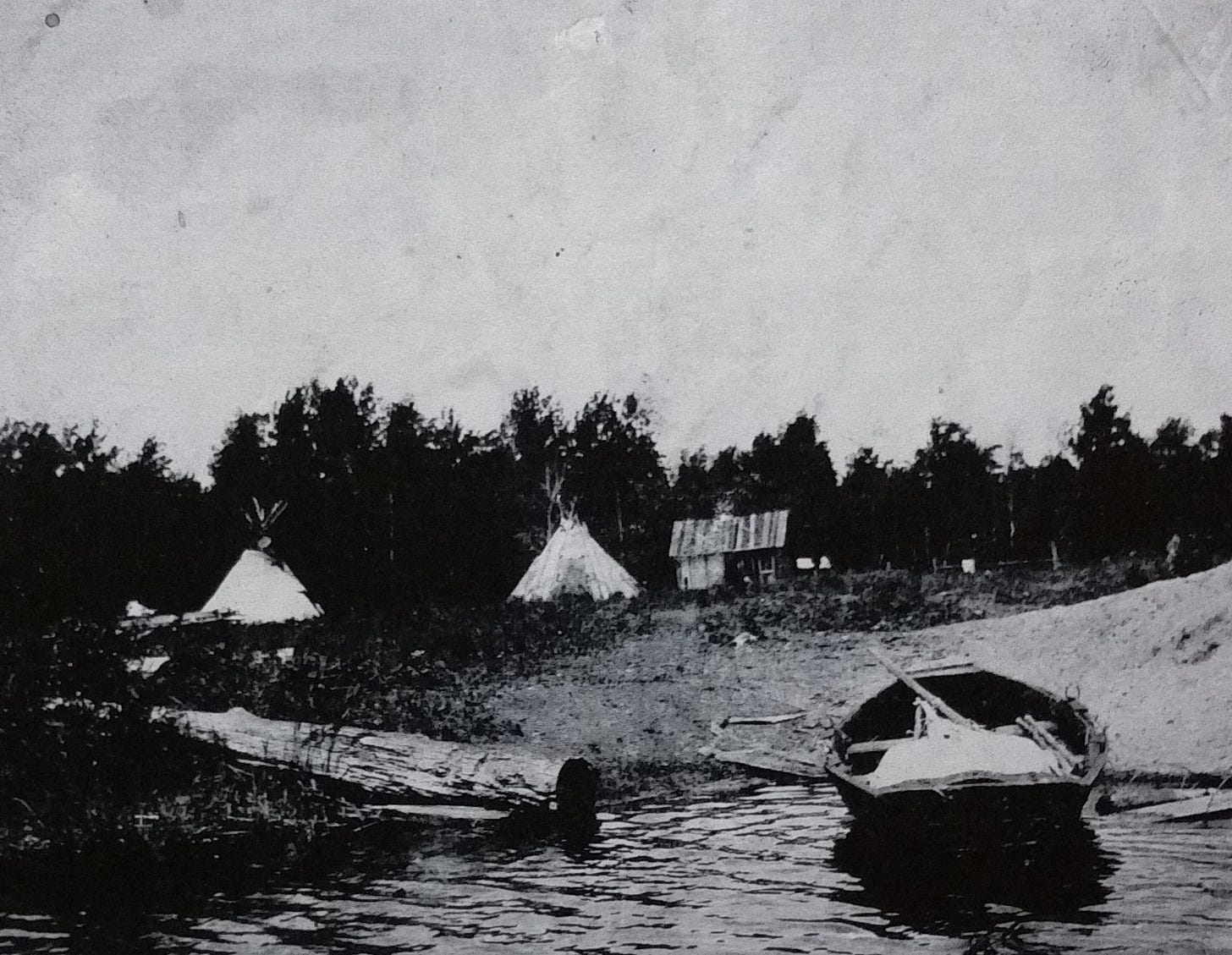

Mr. Duncan Begg had married Jane Rutherford Boulton, the “half-breed” daughter of Joseph and Mary Boulton. Their first daughter was born in 1872 at the Northwest Angle, and she died there in 1873. Duncan Begg’s two eldest sons, William and James, married the Muggaberg sisters whose father was Norwegian and mother was Scottish-Métis. 1

Mr. Duncan F. Begg had been hiding from me in plain sight. He worked for the Hudson Bay Company and translated at Treaty 3 negotiations in October of 1873. Mr. Begg had certainly known Naymaypoke’s father, Chief Ay Ash Wash.

The mysterious Mr. Begg is Métis. In the US, Métis has meant mixed ancestry and it is a contentious term. Along the Canadian border here, Scottish-Métis refers to people of mixed lineage traced back to the late-1700s when Lord Selkirk led Scottish immigrants to what was known then as the Rainy River Settlement. Métis identity is not simply the result of a dual bloodline, but a matter of a singular cultural heritage of dual origins.

Frank Begg as a character in this story deepens my understanding.

Finding him reveals the presumption he was of European descent and my suspicions of his motives. He had moved from Kenora, Ontario, to Warroad in 1894, about a decade before the school district paid Naymaypoke for the land.

Three generations in the Begg family. Julius Begg — Edith’s older brother and Duncan’s grandson — married Johanna Dumais, a Métis woman whose parents lived in Warroad. How many children with the last name of Dumais had I assumed to be white?

Duncan Frank Begg was likely not the only person in Warroad whose lineage included Ojibway or Cree mixed with European heritage.

I had skimmed through the attendance rosters and saw no Ojibway student names. Or were they invisible to me? To assume a family surname of European origin meant the pupil’s parents were white means I have either forgotten or ignored how many immigrants changed their surnames when they came to America, how many descendants of enslaved people bear the surname of their ancestors’ owner-captors, how many Ojibway names had been Christianized. I confess, I hadn’t even considered the likelihood of mixed lineage with European immigrant fathers.

I returned to the student rosters and looked at parents’ nationality. Entries of Canadian and American gave me pause. American implies the parents had been born in the US; they’re not immigrants. Listing the nationality of Canadian may have meant more than on which side of the border they were been born. Canadian might also have meant Métis.

Or Ojibway. The border between the US and Canada cut across Lake of the Woods — drawn in 1782, surveyed in 1824, redrawn again in 1842 — while the Kah-bay-kah-nong canoed back and forth across the boundary lines. They had a long history of authorities in Minnesota telling them they were Canadian Indians and Canadians telling them they were American Indians.

Scrutinizing student records for clues, I have to admit that if I didn’t know the Christian names on Chief Ay Ash Wash’s family tree, I would never have recognized these to be Indian students:

George Marshall.

George and Albert Angus.

James, Blanch and Peter Accobee.

Louis Goodin.

Alice Caron.

John Lightning.

The annual list of enrolled students has pages of names with gender, date of birth, age, name of parent or guardian, and post office. This last page of the official school census of 1925, separate from the others, is where I found the names I recognized to be descendants of Ay Ash Wash. The list segregates them without any textual reference to their demographic category of Indian.

While I don’t think I found any Indian students enrolled from 1905-1915, the first decade after Naymaypoke sold the land, now I can’t be so sure.

Did I think Edith Begg was white? You betcha. The notation of Norwegian and Scottish erased her Métis heritage. I only discovered it because I looked for more information about her relation to Naymaypoke’s translator.

I made false assumptions about who is white and who is Indian, which I find hard to admit, much less put into words how that happened so easily or why.

These details about the people who lived side by side in Warroad — Ojibway, Swede, Norwegian, Métis, French, Canadian, German, Scottish, English and Irish — paint a more complex picture.

Finding Mr. Begg in the historical archives shows me what assimilation looked like in 1905 — beyond the assimilation of Indian land for the purpose of public education in Warroad.

School for the children of immigrants who spoke Swedish, Norwegian, German, and French assimilated foreigners using English. Education worked to erase ethnicity and homogenize culture. These attendance records had made Ojibway and Métis students indistinguishable from homesteader’s children.

Perhaps this absence of any written school board policy regarding Indian student enrollment and lack of any records of their attendance between 1905-1915 is evidence — evidence of decades of assimilation already at work.

Perhaps this absence I observed reflects my unconscious biases and limited perspective as the great-granddaughter of Swedish immigrant homesteaders.

Or perhaps it means Indian children did not attend school during that first decade of the school district in Warroad.

Perhaps I can learn more.

Duncan Begg’s daughter Mary married Frank Clement. Their daughter, Sarah, married Tom Thunder.

The caste system of the world is complicated - Isabel Wilkerson's book, Caste, is so very helpful in doing some of the unraveling. I just so value people like you and her who are enabling the light to shine through the cracks.

So much of history is obscured by misspellings, misunderstandings, and biases. I think you are being hard on yourself - something didn't feel right, and you kept digging. It's a testament to your perseverance as a researcher that you reconciled a misattribution.