A love story on Lake of the Woods: Tom and Sarah Thunder

Their families made history at Treaty 3 negotiations before they were born

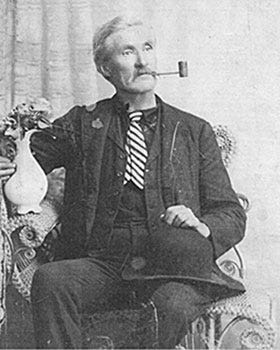

Tom Thunder was the eldest son of Gaybayashquay, the chief at Buffalo Point, known as “Old Jim Thunder” (1878-1936), grandson of Chief Animikeese (“Frank Little Thunder,” 1830-1905) and great-grandson of Chief Ay Ash Wash (1790-1899).

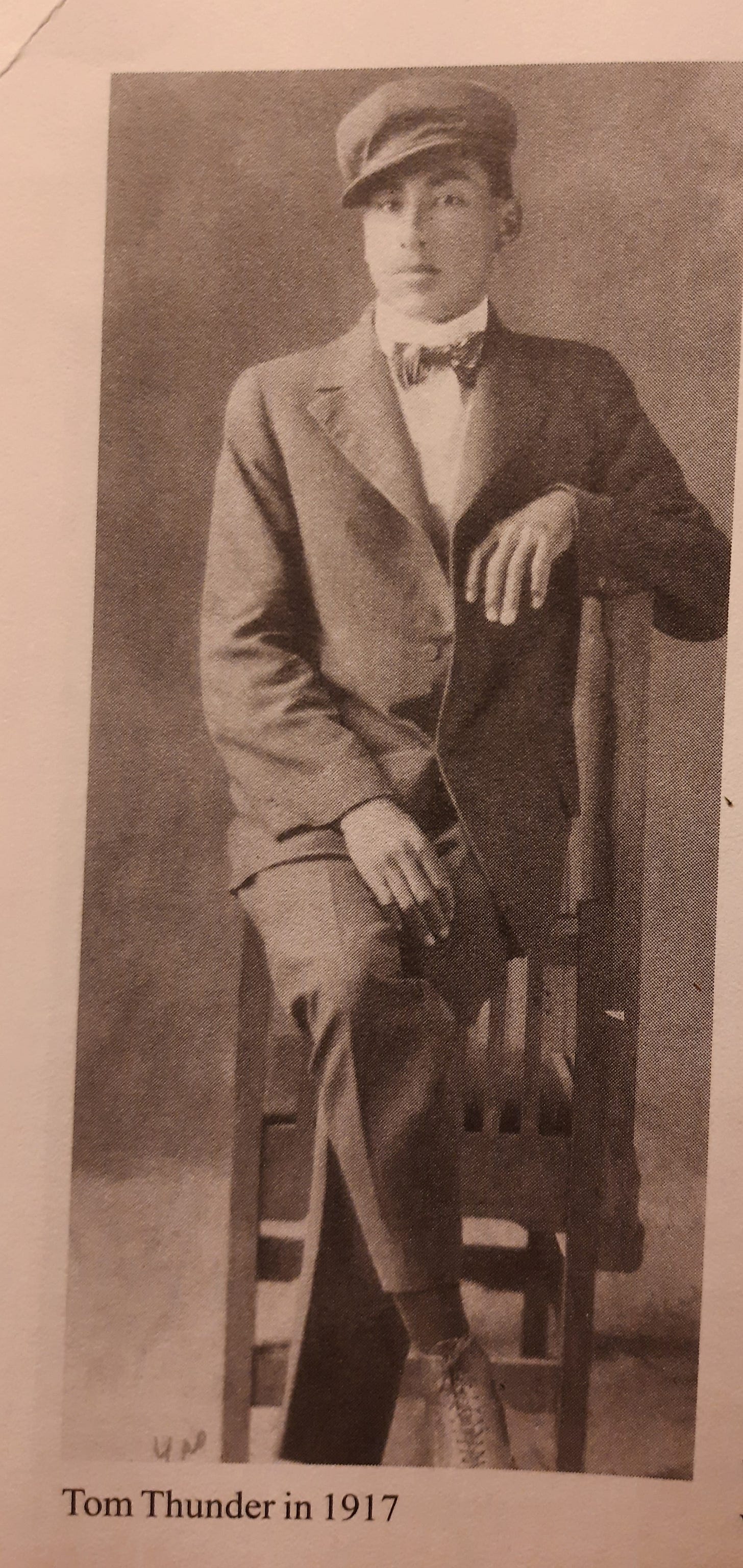

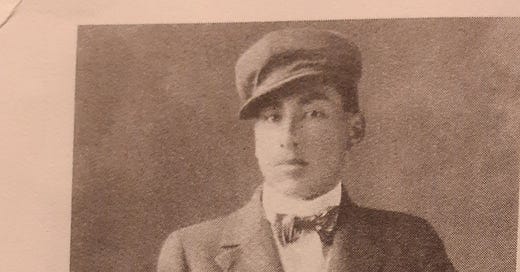

When his portrait was taken in 1917, Tom Thunder was 20 years old. It was around then he met 15-year-old Sarah Clement, who would one day become his wife.

In the Warroad Heritage Center and Roseau County Museum I had not found much information about Tom Thunder before the 1950s when newspaper clippings and photographs started showing up of Tom and Sarah as an older married couple.

Who was Sarah? I had learned her maiden name was Clement and found her father Frank had been one of the early Roseau County settlers when he arrived in 1898 in Warroad to stake a land claim.

He had come west as a young man — born in Massachusetts — and married Sarah’s mother, Mary Begg, in Warroad.

Frank Clement filed a claim on a quarter-section in Longworth, six miles north of Warroad on the border and eight miles west of Buffalo Point. He cleared 140 of the 160 acres in Longworth and sold wood for $1.25 a cord, according to Pioneers! O Pioneers!1 He also drove a team of horses and a wagon, hauling dry goods from Stephens, Minnesota — nearly 100 miles — to the general store in Warroad.

Frank Clement built a big farm house on his homestead in Longworth, which is where his wife gave birth to their two daughters, Margaret and Sarah.

In 1903, running late one day to catch the train out of Warroad to Longworth with an armful of groceries, Frank Clement slipped and fell when he tried to jump on the moving train. Both of his legs were severed and he spent six weeks in the hospital in Rainy River (Ontario) before he returned home, unable to work.

His daughter Sarah was eleven months old when her father lost his legs.2 Montly compensation from the railroad for the accident was $6.00. Sarah’s mother walked to Warroad from the farm and hired out as help for a dollar a day.

Sarah remembered her childhood as picking strawberries for twenty-five cents a quart, gathering eggs to sell for a dime a dozen, and churning butter for fifteen cents a pound.3

Sarah’s father eventually learned to push himself around on a wooden platform outfitted with wheels (and in winter, skis). His wife plowed and he gardened. Frank Clement eventually figured out ways to cut and split firewood for sale.

It wasn’t until I crossed the US-Canada border and visited Buffalo Point Museum and Government Centre that I figured out from a photograph mounted on display that Sarah’s mother, Mary, was the daughter of Duncan Finlayson Begg.

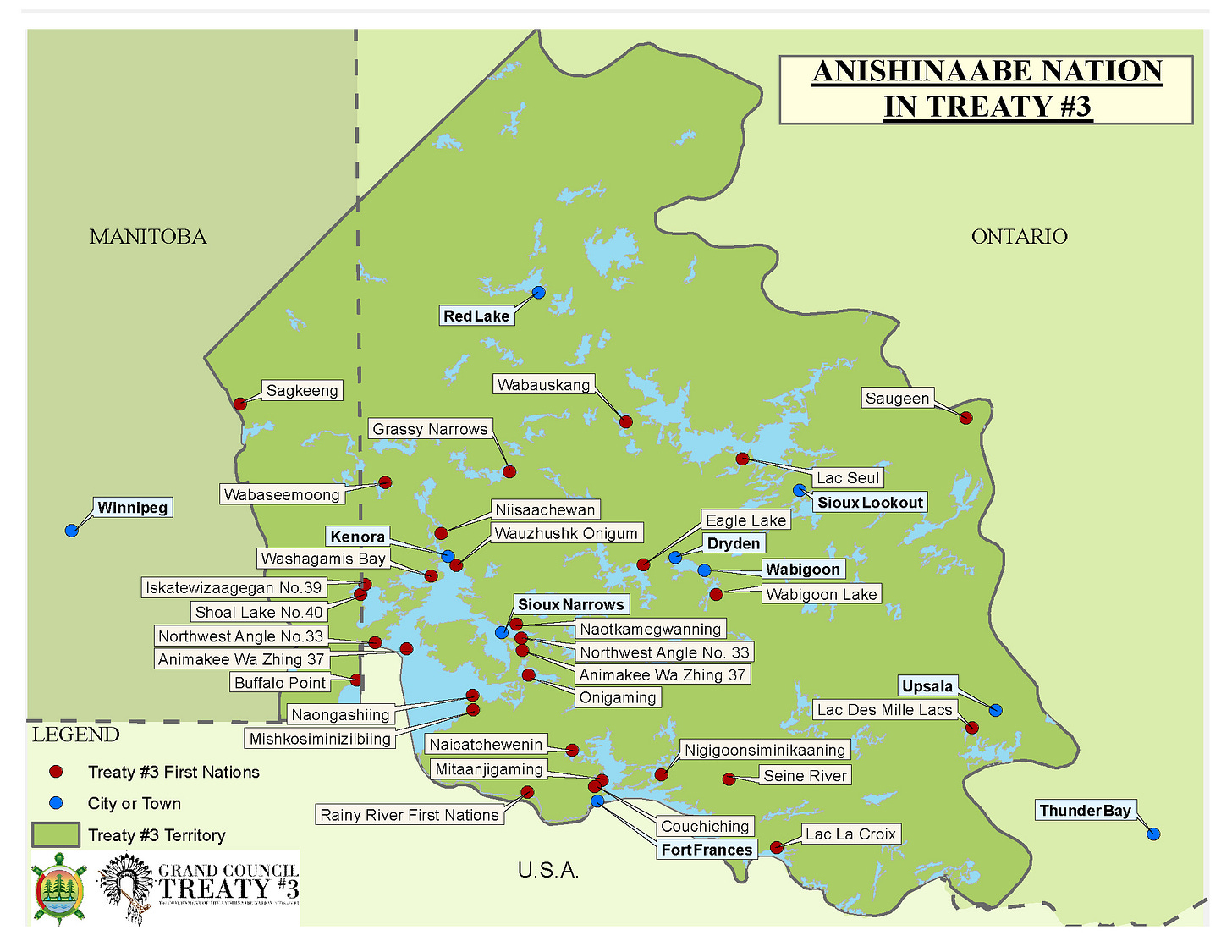

Duncan Begg originally came from the Scottish-Métis community in Selkirk, Manitoba, to the Northwest Angle where he lived when he worked for the Crown as an interpreter at Treaty 3 negotiations at the Northwest Angle in October of 1873.

Sarah’s grandfather had to have known most of Tom’s extended family. Tom’s paternal great-grandfather Chief Ay Ash Wash went to the negotiations at the Northwest Angle. Tom’s maternal grandfather Chief Wahsawbeetung (Handorgan) was there, too. Chief Powassin — married to Tom’s paternal great-aunt, Minogeshigoke, known as “Laughing Mary” — also participated along with 21 other chiefs of the Lake of the Woods Indians in the Treaty 3 negotiations.

Treaty 3 is historically significant for many reasons but particularly so because it involved the lands and waterways of what is now Ontario and Manitoba, including most of Lake of the Woods.

I found it interesting that the families of Tom and Sarah were closely connected though a historical event which took place on Lake of the Woods a quarter-century before either of them were born.

Their families had made history with the signing of Treaty 3. But when I dug deeper into the events at the Northwest Angle, I discovered during October 1873 there had been an altercation between Begg and Powassin, the chief of the band at the Northwest Angle. A Begg family source on the Red River Canadian Ancestry site reported, “the Chief insulted him over some bargaining for goods” and Duncan hit him and claimed Powassin was “the only Indian I ever struck in my life.”

What had Chief Powassin done to make him so mad?

Powassin had hired a scribe who made a written record of what the chiefs understood they were agreeing to when they put their x marks on the Crown’s document. This version of the agreement is known as the Paypom treaty.

Turns out the terms and conditions in Treaty 3 did not correspond to the Paypom document. The Ojibway had been snookered. They had not agreed to cede their land or the lake to the Crown, but grant right-of-way access to the new Confederation of Canada so they might pass through Anishinaabe lands as they built their Dawson Road to Fort Garry (Winnipeg). In exchange for peaceful passage across land and shared access to the waters, the Lake of the Woods Indians had agreed to accept payments in cash and goods in perpetuity. They did not relinquish their hunting, fishing, or mineral rights.

Chief Powassin may have insulted Duncan Begg over the bargaining of goods at Treaty 3 negotiations, but perhaps Powassin had cause to challenge Begg’s interpretation of things.

No further confrontations are known to have occurred between the men.

When Tom Thunder (1898-1977) and Sarah Clement (1902-1997) fell in love, four decades had passed since their elders met at the negotiations of Treaty 3 at the Northwest Angle.

I don’t know when or where or how Tom and Sarah met.

I do know from what they told others in public much later in life is that they had wanted to marry when they were younger but were not permitted.

But I don’t know why. Did their families object? According to one source — Tom’s great-grandson John Thunder4 — Sarah’s family would not allow it. Because her mother and disabled father depended on her? Because her grandfather held a grudge? And I have to wonder whether Tom’s elders would have approved of the match. If they weren’t allowed to marry, why not? I don’t know.

I don’t know how or why Tom and Sarah split up, but the relationship apparently ended when she could no longer hide her pregnancy.

I do know Sarah gave birth to Tom’s son, Oliver L. Thunder, in 1922. In less than two years, she married Fred Conover, who had a farm a few miles south of Warroad. Sarah had three more children: Helen, James, and Catherine.

I have so many unanswered questions. Was Oliver with her on the Conover farm? If so, was Fred Conover a good stepfather? Did Sarah love Fred? Did he love her? Did he love his children? There is so much I don’t know.

I do know their marriage did not last. Fred Conover left Sarah with the two younger children, James and Catherine. Conover denied he was the father of James and Catherine, according to James’s son. Conover took his daughter Helen and moved west to the state of Washington.

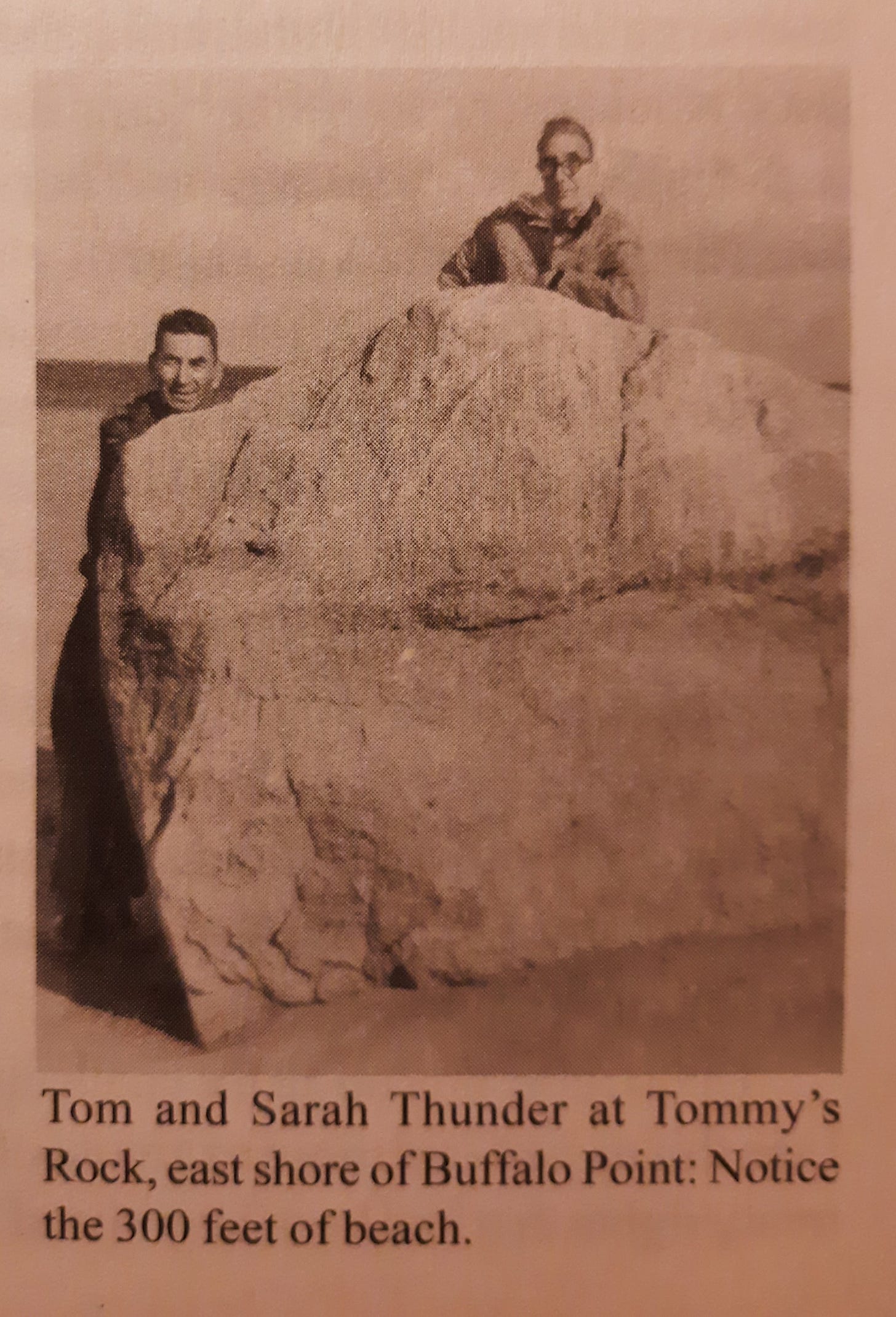

Tom and Sarah reunited in the early 1930s.

They married and moved to Middlebro, Manitoba, a small village due west of Buffalo Point about 10 miles. There they built a house in the woods and raised their son, Oliver, and her children, James and Catherine, who Tom adopted. Tom and Sarah had three more children: Glen, born in 1935, Dorothy in 1938, and Frank in 1941.

C’mon back next week to find out more about the family of Tom and Sarah Thunder and the history of Buffalo Point First Nation.

Pioneers! O Pioneers! published by the Roseau County Historical Society, 1976. Most of the Clement family details came from this source compiled from family files and archival materials in the Roseau County Museum.

Pioneers! O Pioneers!

Pioneers! O Pioneers!

John Thunder, interview October 2024, and in Buffalo Point: Rising to a Higher Level (2012).

What happened to these people, as you continue to describe their circumstances, imho, is beyond "snookered"

This is from an article from the March 27, 2025 NYRB

An Expanding Vision of America by Nicole Eustace [is the Julius Silver Family Professor of History at New York University. Her book, Covered with Night: A Story of Murder and Indigenous Justice in Early America won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for History.

She includes the review of three books in what she has to say about indigenous people and their historical significance:

Native Nations: A Millennium in North America by Kathleen DuVal

Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America

The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of US History by Ned Blackhawk

Here are the last two paragraphs:

The expansion of the United States, far from being accomplished by virtuous farmers and liberty-loving patriots somehow able to float above the sordid history of imperialism, relied on remarkable levels of rhetorical and physical violence. Blackhawk insists that we must reckon with the fact that no sooner did Europeans set food in America than they began systematically despoiling the continent and its peoples. At every critical point in the subsequent political and economic development of the United States, purloined Native resources proved pivotal. Together with the forced labor of enslaved peoples of Africa and the Americas, stolen lands and resources made possible the creation of the world’s first modern constitutional democracy. *

Reconciling the reality of mass thievery, enslavement, suffering, and death with more familiar and comfortable stories of the spread of liberty, prosperity, civility, and law is an enormously difficult task. Yet only by confronting the complicated facts of collective past may the United States today move toward greater truths, toward new forms of redress for Indigenous peoples and descendants of the enslaved, and toward the recuperation of the nation’s finest values—freedom, equality, and opportunity. There are not shortcuts and no fairy-tale flying machines to take us there, but there are strongly researched and written books of history that may help us begin to work toward the realization of America’s most lofty promises.

*See Martin Loughlin, “the Contemporary Crisis of Constitutional Democracy,” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, Vol 39, no. 2 (2019), pp. 435-454.

This could be a book in itself! To tell their stories of intersecting lives, family background, colonial and tribal histories, and how boundaries, both familial and state/nation, are challenging. As always, thank you for your angles and research.