Memorial Day began as a way to honor Union veterans after the Civil War. Historians now recognize its first observance on May 1, 1865 — less than a month after General Robert E. Lee surrendered — when more than a thousand emancipated slaves in Charleston, South Carolina, held a parade for fallen Union soldiers.

Warroad, Minnesota, may have been far away from Civil War battlefields, but its proximity to the struggles which had divided the nation are too easily forgotten. Congress enacted the Homestead Act a year after the Civil War began in the spring of 1862. The promise of free land to those who would not take up arms against the Union brought white settlers westward.

And settlers kept coming, encroaching on Indian territories in violation of treaty agreements. Congress passed the Dawes Act in 1887 to divide up tribal reservations into allotments assigned to individual Indians so unallotted lands could be claimed by homesteaders like my maternal great-grandparents.

There is a connection between the Civil War and Warroad found buried in Riverside Cemetery.

His name was William A. Stewart.

Stewart was the last Civil War veteran buried in Roseau County, Minnesota. He was born in Indiana County, Pennsylvania, on December 16, 1846. That would make him about the same age as Kakaygeesick.

The government-issued gravestone of William A. Stewart at Riverside Cemetery is a four-inch slab of white marble about ten inches wide with a curved top, standing about a foot high. The date of his death at the age of 86 was January 2, 1933. The 1930 Census showed him to be a resident of the Berg Family Boarding House in Warroad.

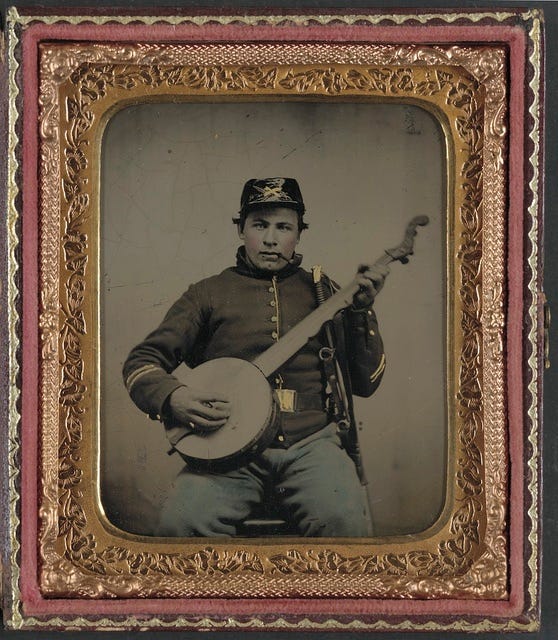

Stewart mustered into the 55th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment on August 20, 1862, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Promoted from Private to Musician, he accompanied his regiment on General Sherman’s expedition through South Carolina to victory at the Appomattox Court House in Virginia.

Musicians during the Civil War were often assigned to drive ambulances, carry stretchers, tend the wounded, and collect corpses. Sometimes they were ordered to fight. William Stewart’s regiment fought at Drewry’s Bluff, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, the Battle of the Mine, Chaffin’s Farm, Rice’s Station, and at the Appomattox Court House.

It is hard to fathom what he may have witnessed.

William A. Stewart was discharged on July 11, 1865; three months after the end of the Civil War.

I wondered how he had found his way to Warroad, Minnesota, so I started digging for more information. What I didn’t expect to learn was what happened to the Stewart family before William enlisted.

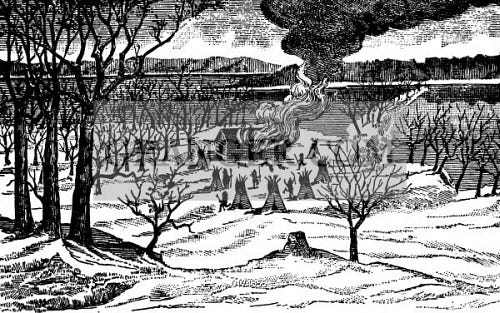

His parents had moved from Pennsylvania to the northwestern corner of Iowa near the Minnesota border at Spirit Lake in 1856 when he was 10 years old. Part of a wagon train, they settled on Dakota land with several other families before winter set in.

The Wahpekute band of Dakota — on whose land they settled — had been camped about 10 miles north when the wagon train arrived. They had never agreed to cede Dakota land and Chief Inkpaduta had refused to sign any treaty, even after a white whiskey trader killed his family and the prosecutor put his brother’s head on a pike. With game scarce and an early blizzard in December of 1856, they spent that harsh winter near Loon Lake.

When the Wahpekute band of Dakota returned home in March of 1857, they found white settlers had moved in and built cabins. Led by Chief Inkpaduta, the Wahpekute attacked and killed 38 white settlers, including William’s parents. He and his brother John survived.

Many historians consider the incident at Spirit Lake the precursor to the Dakota War. That war ended with the public hanging of 38 Dakota men in Mankato on December 26, 1862.

Five years after their parents died, the Stewart brothers had gone in different directions. William returned to Pennsylvania where he enlisted in 1862. His brother John went north to homestead in Olmsted County, in southern Minnesota, where he married and raised a family.

After the Civil War, William Stewart returned to Pennsylvania where he married Elizabeth Rhine in 1873 and had two daughters. I have not been able to determine exactly when he arrived in Warroad or even what musical instrument he played. Yet unearthing his story as a Union veteran of the Civil War seems fitting for Memorial Day weekend even if my research remains incomplete.

There's a brand new article in The New York Times about Army musicians and includes some history: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/27/arts/music/military-bands-west-point-army.html?unlocked_article_code=1.vE0.GbiA.6VwPcHZ5lmSY&smid=url-share

I agree with the importance of local specific place connections. One of my great-grandfathers who homesteaded near our family farm in southwestern MN, was a courier during the Civil War and he had a close friend who played fife during the conflict. Later the two veterans homesteaded just one mile apart in the early 1870s.