Did Chief Naymaypoke give or sell his land for the school in Warroad?

preliminary report on findings from 1904-1905 school records

How did the school district of Warroad, Minnesota, acquire land allotted to Chief Naymaypoke?

I didn’t know, even though I’ve spent almost a decade researching the land allotted to his brother, Kakaygeesick.

When Congress further diminished Red Lake Reservation in 1902 to the area south of Upper Red Lake under the Dawes Act, hundreds of thousands of acres opened up to homesteaders and the timber industry.

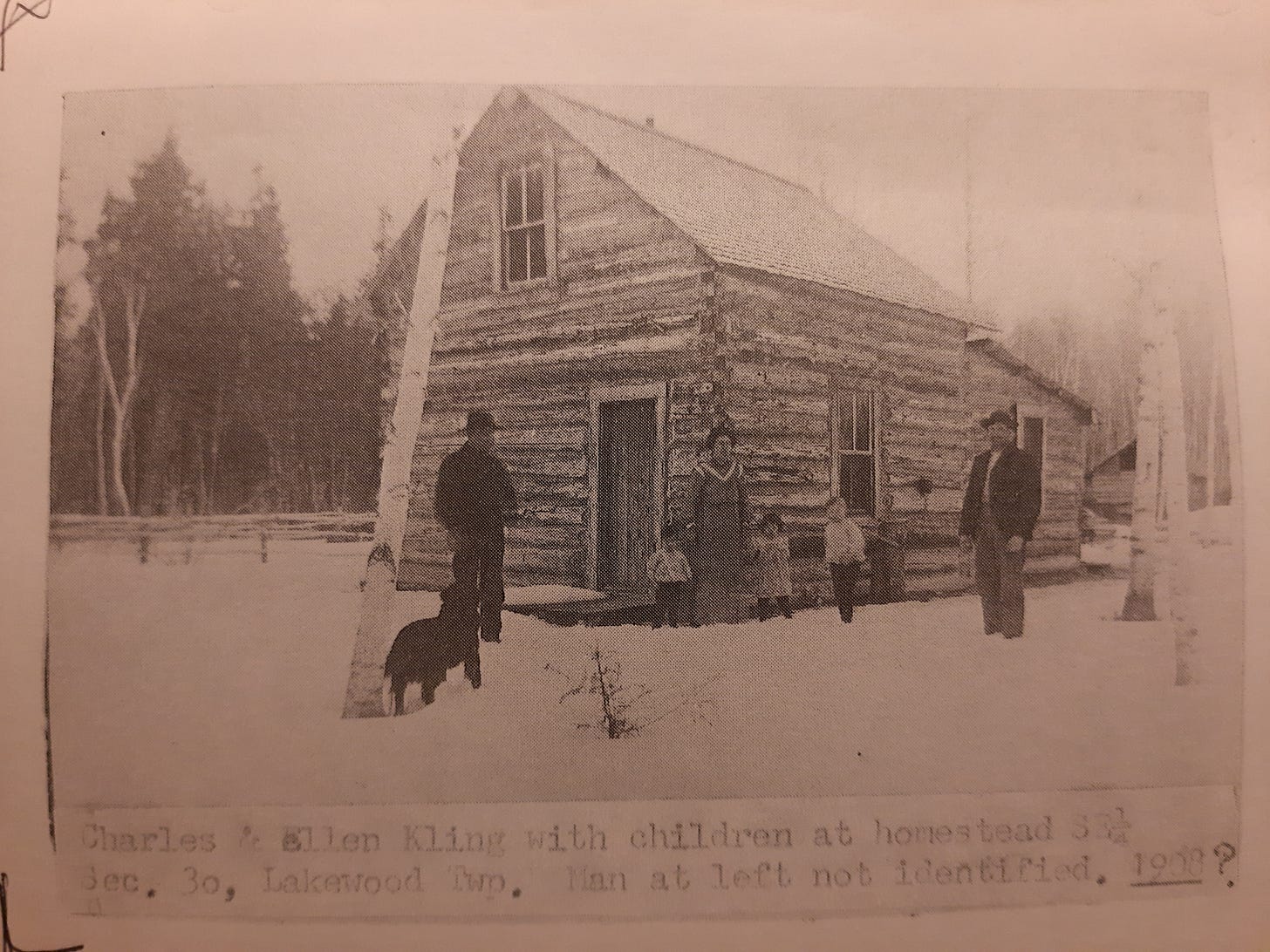

My maternal great-grandparents, Charlie and Ellen Kling, arrived in 1903. Ellen’s sister had already moved north with her husband. Charlie brought his family, including his brother, brother-in-law and mother-in-law to the Swedish settlement at Willow Creek east of Warroad.

Warroad had already become a city in 1901. Since the 1880s, whites settled among the Kah-bay-kah-nong Indians at this trading post well-established since the late 1700s. Many whites arrived long before federal policies regarding allotments or homesteads went into effect here in northern Minnesota.

Since the school district is a public entity, I felt certain there had to be some clues in the records from the earliest days of the district as to how it acquired the land, a four-acre parcel of Naymaypoke’s allotment.

Thanks to my sister, Barb Nelson, who spent days photographing records at the Gale Family Library at the Minnesota History Center, I deciphered the exquisite penmanship found in these bound editions of the 1904 and 1905 school board minutes from Warroad.

They begin in January of 1904 with the resolution to establish an independent school district. Warroad Schools had operated under the auspices of the Roseau County School District since 1896.

The first order of business was the appointment of school board members, oaths of office, election of officers and approval of bylaws. Their deliberations during 1904 included school building maintenance, textbook orders, and bill payments. They also hired teachers and Mr. Begg, who took care of the school. There is no mention of school district property except reference to an existing schoolhouse of inadequate size.

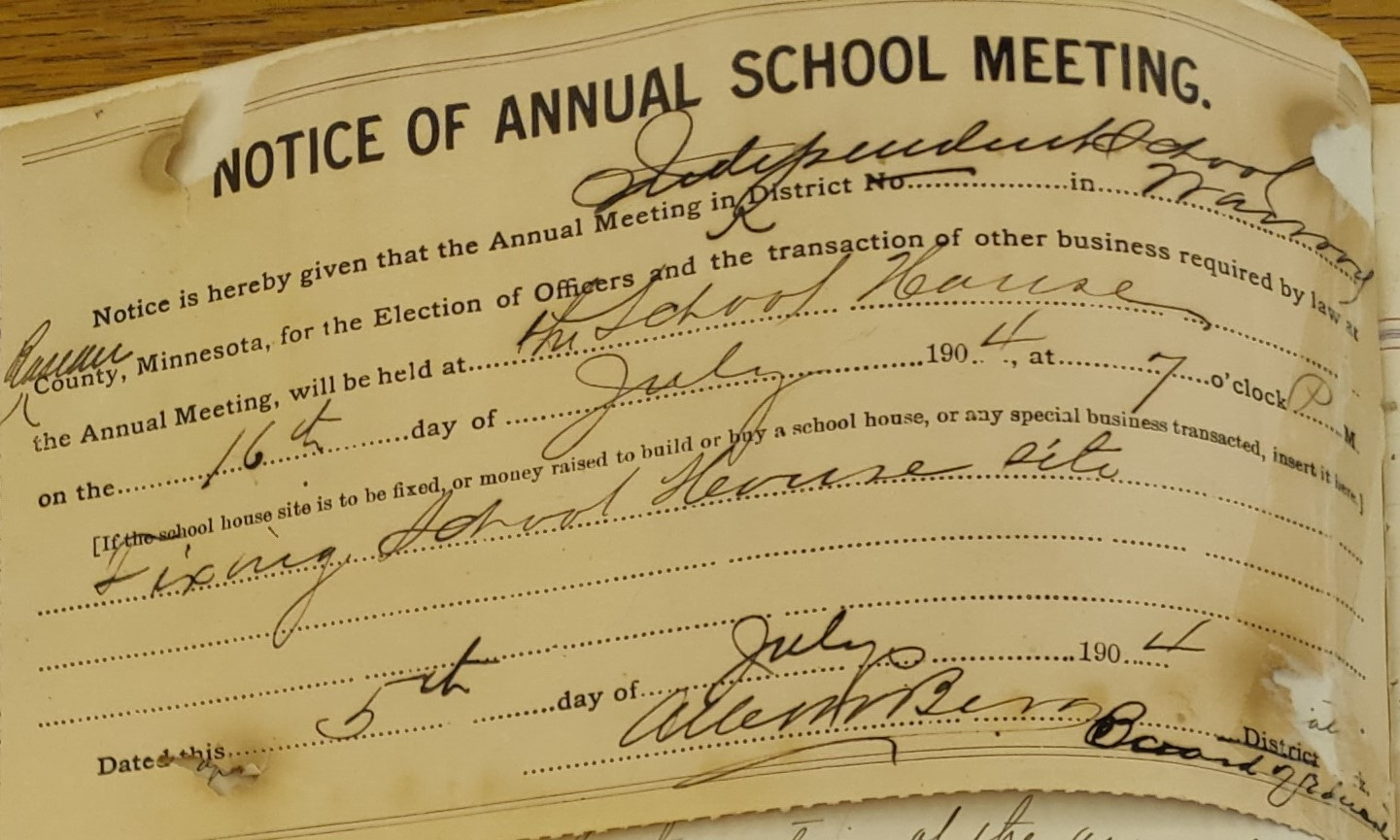

In July of 1904, public notices are posted about the annual school meeting. Notice the meeting is scheduled to take place at “the School House” for the primary purpose of “fixing School House site.”

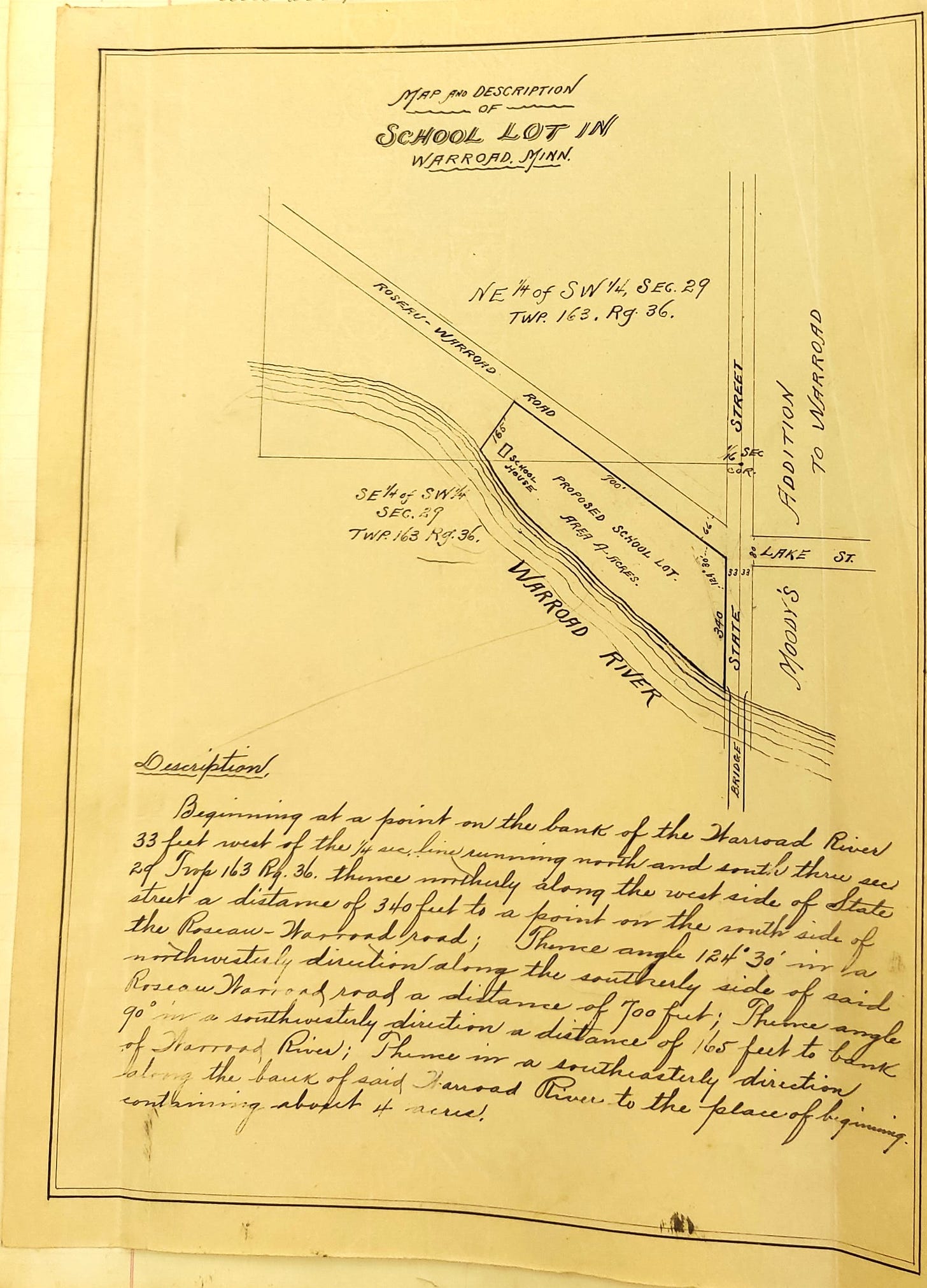

In preparation for the annual meeting, the school board included a map and description of where exactly they planned to fix the site. In the center of this map (shown below), the small square indicates the location of the School House. This four-acre parcel identified in 1904 as the “proposed school lot” lies within the boundaries of what will be officially granted in 1905 as an allotment to Naymaypoke by the federal government.

Apparently, this four-acre parcel was the only location under consideration at the annual school meeting. From my reading of the minutes and local historical archival sources, the map indicates the location of the school building in use in 1904. There are references to its log construction.

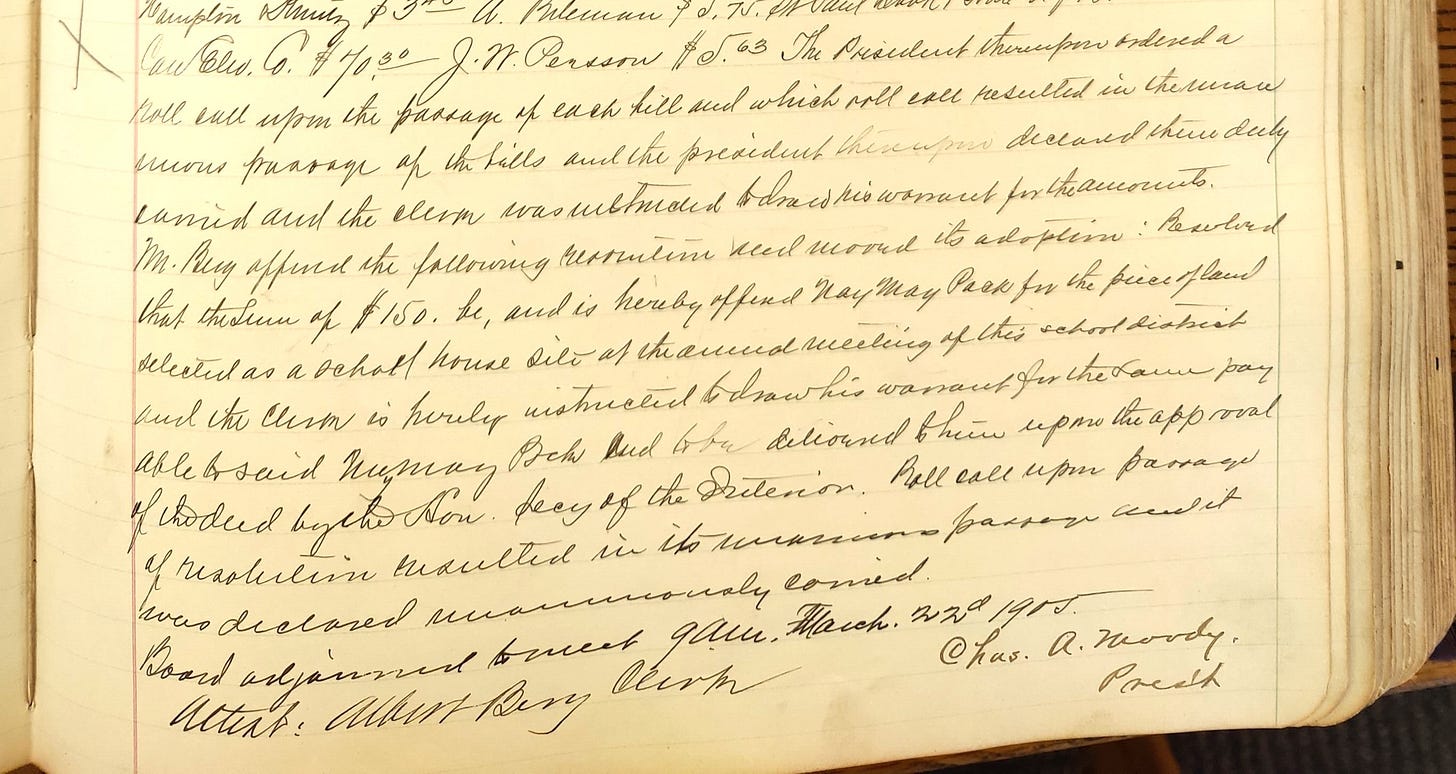

There is no mention of school property until March 21, 1905. Albert Berg introduced a resolution. I quote from the passage photographed below:

“Mr. Berg offered the following resolution and moved its adoption: Resolved that the sum of $150 be, and is hereby offered NayMayPuck for the piece of land selected as a school house site at the annual meeting of this school district and the clerk is hereby instructed to draw his warrant for the amount payable to said NaMayPuk [sic] and to be delivered their [sic] upon the approval of the deed by the Hon. Secy. of the Interior. Roll call upon passage of resolution resulted in its unanimous passage and it was declared unanimously carried. Board adjourned to meet again. March 22, 1905 Chas. A. Moody, Pres’t. Attest: Albert Berg, clerk.”

The school board extended an offer to pay Naymaypoke. The historical record would seem to suggest Naymaypoke had not offered to sell. There are no records of any meetings, negotiations, or counter-offers. Nor is there any record of a request to use the Warrior mascot for school sports teams; which is what had led me down this fascinating research rabbit hole.

Whether Naymaypoke voluntarily sold his land isn’t an easy question to answer. Especially since a school house had been there since 1896. Historians refer to this period of dispossession of Indian lands after the US-Dakota War as “encroachment.”

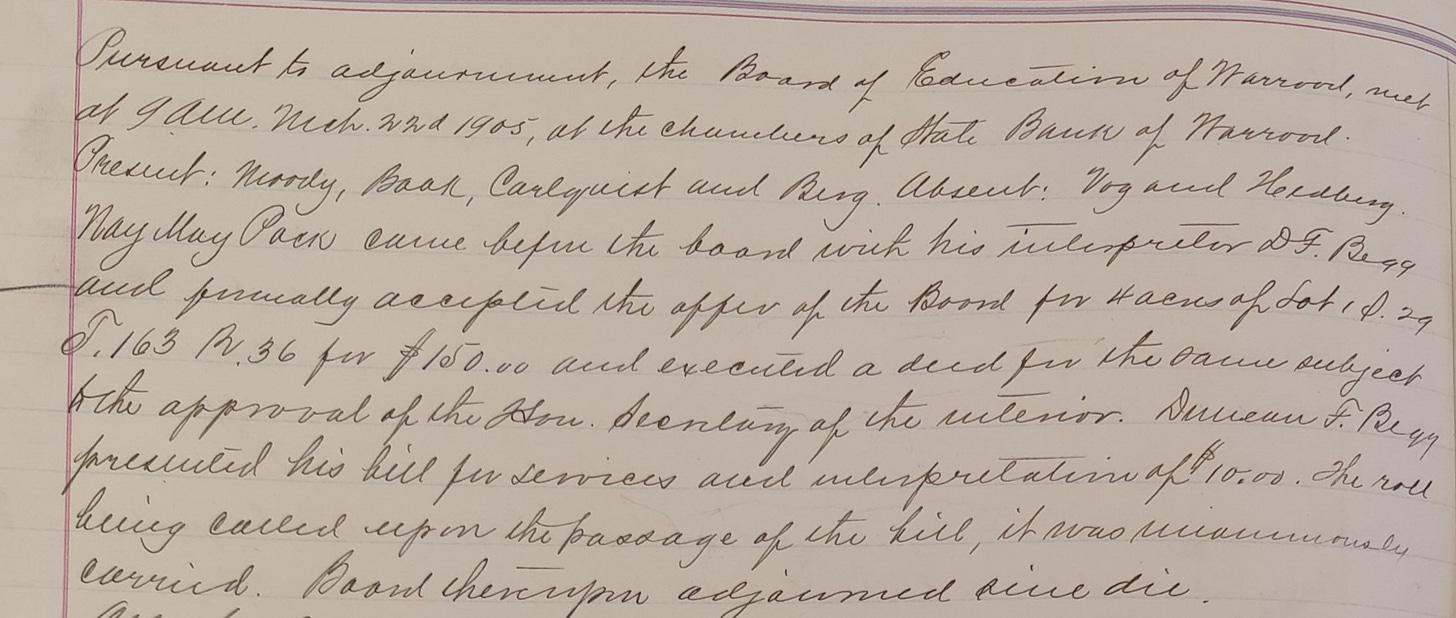

The day after the board adopted the resolution to purchase the 4-acre parcel, the school board members gathered again for an official meeting at the State Security Bank at 9 am on March 23, 1905. The school board minutes reflect Naymaypoke appeared and accepted their check for $150.

“NayMayPuck came before the board with his interpreter D. F. Begg and formally accepted the offer of the board for 4 acres of Lot 1, S[ection] 29, T[ownship] 163, R[a]n[ge] 35 for $150.00 and executed a deed for the same subject to the approval of the Hon. Secretary of the Interior. Dreveau F. Begg presented his bill for services and interpretation of $10.00. The roll being called upon the passage of the bill, it was unanimously carried.”

Mr. Dreveau F. Begg worked for the school district as the caretaker of the school building and grounds. I wonder what his relationship to Naymaypoke may have been and how he happened to have learned to speak the Ojibway language. What doesn’t appear on the pages of the school records pulls me deeper into the mystery.

Did Chief Naymaypoke voluntarily sell his land? Did he want to sell his land? Did he have any choice?

Might the better question be whether the school district paid Naymaypoke for the land it had taken?

The legend that Naymaypoke gave the land to the Warroad Public School so Indian children could attend falls apart like the lore about the Warrior team mascot in the face of the historical facts presented in these school board minutes.

Next week I’ll share what I learn about whether Indian children were enrolled in Warroad Public Schools and when.

Thanks for digging into this, Jill. It's a revealing bit of history about how easily the Native presence on this continent was erased, and how hard it is to unearth the real stories behind the official accounts (the conquerers always get to write the history they prefer).

I remember reading some of the writings of Anne Firor Scott that revealed stories written by Southern women in their diaries quietly expressing their objections to their husbands owning of slaves. We generally assume that these Southern women did not intend for there to be any "public" readings of their diary entries, but eventually what they wrote was exposed. It makes me wonder if any of homesteader women kept diaries or private writings or letters that provide some clues to the mysteries you keep identifying. If the Indian children did attend this school and had experiences similar to other Indian children sent away to boarding schools, I rather doubt the accounts would be "pleasant". I would assume the general disregard that many homesteader people had for the Indian population would have been transported into the schools. I hope you will find more about this in your research.