When Red Lake Indian Agent Walter F. Dickens sold two parcels of Namaypoke’s allotment in 1914, he told The Warroad Plaindealer they would build a house for the chief on his remaining seven acre parcel along the river. They also agreed to pay him the rest of his money in monthly installments, so as to “make him comfortable as long as he may live.”

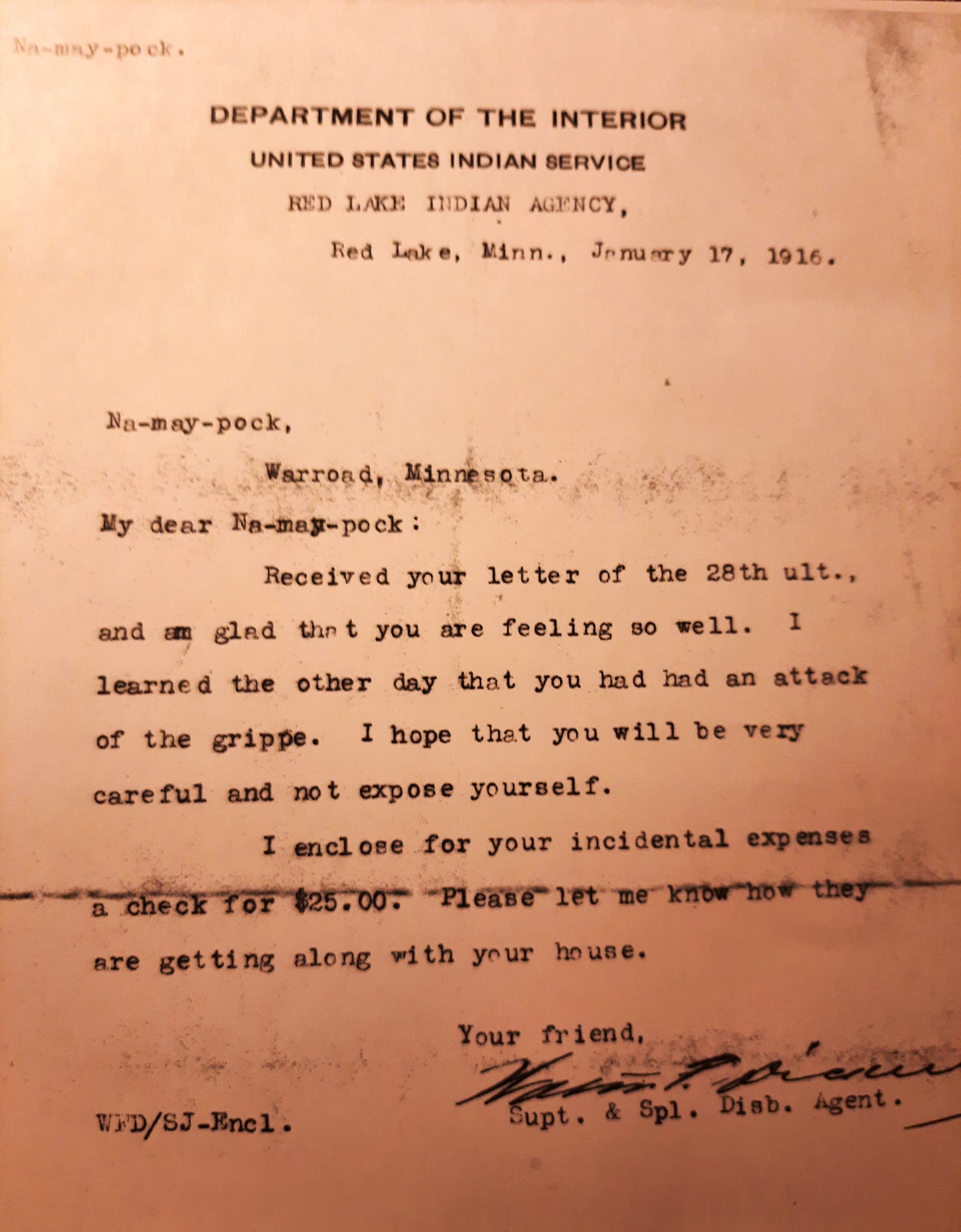

Agent Dickens sent Namaypoke a letter on January 17, 1916, with his monthly check of $25:

Namaypoke did not live to receive his next monthly check. He died on February 15, 1916. A flu epidemic, referred to as “the grip” in national newspaper headlines, spread across the entire country starting in December of 1915.1

When he died, Namaypoke had $5,634.48 on his account at the First National Bank of Bagley, Minnesota. This is likely the balance from the 1914 sale of the two land parcels from his allotment for $7,400, minus the cost of constructing the house and monthly checks of $25 for fewer than two years.

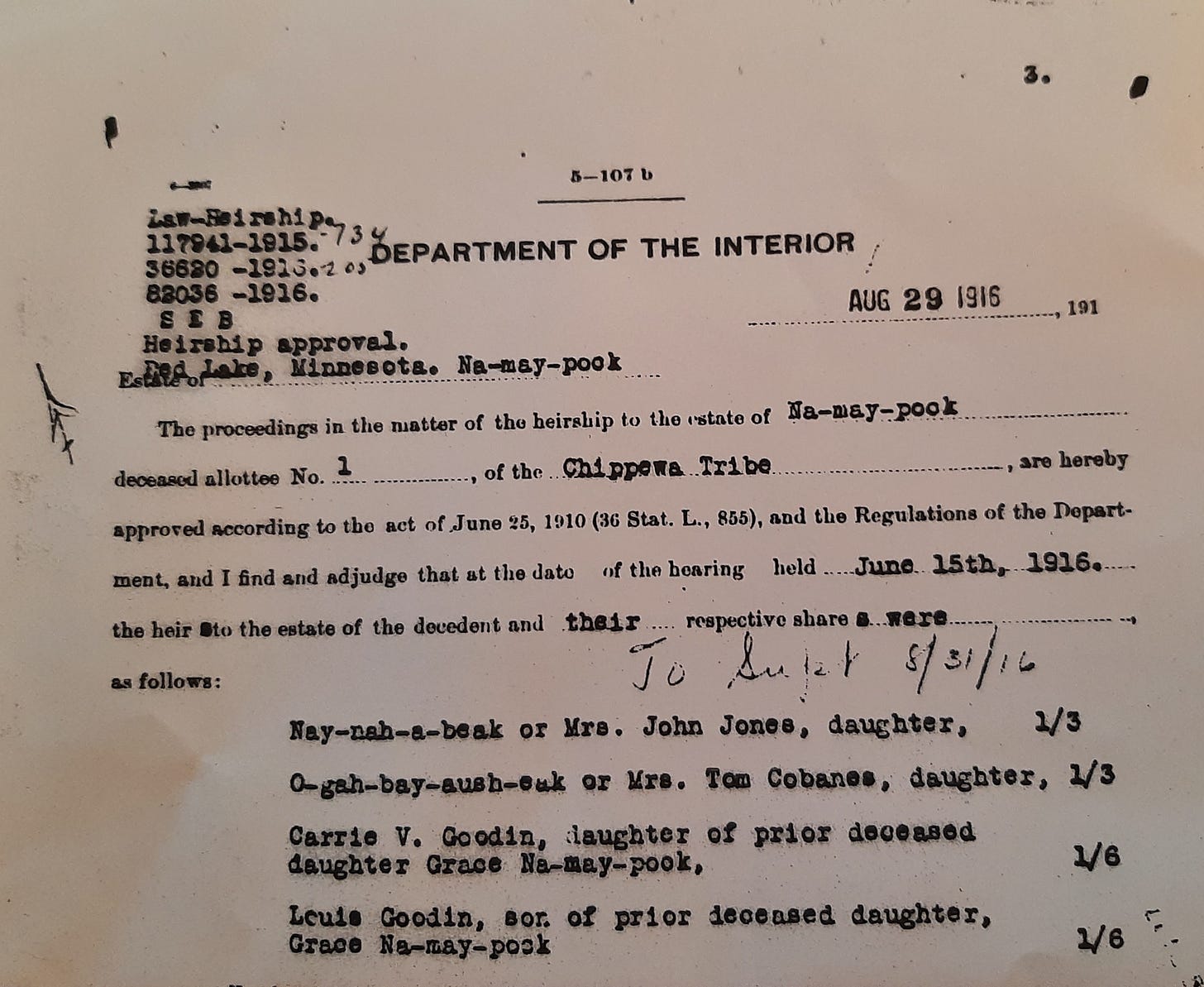

On August 29, 1916, Dickens sent Namaypoke’s documents to the Office of Indian Affairs at the Department of the Interior in Washington, DC, for approval to disburse his assets to the heirs.

As Superintendent of the Red Lake Agency, Dickens was the only person authorized to disburse funds to Indians. In order to settle the estate of Namaypoke, he had to first locate any living descendants who would become beneficiaries of his assets and then had to arrange for payments to be made in small amounts over time.

On June 16, 1916, Dickens visited Warroad and interviewed Namaypoke’s daughter, Anna Jones. Bert Hanson, a Warroad attorney, served as stenographer and his transcipt accompanied Dickens’ submission to the Department of Interior.

During the interview, Dickens asked what relation she had to the deceased Namaypoke (his daughter), on what date he died (Feb. 15, 1916), whether he was married to anyone besides her mother (no) and whether her mother was deceased (yes, more than 20 years).

Anna Jones was 43 years old when her father died. Her Ojibway name is recorded as Nay-nah-a-Beak. She had been their firstborn child. There had been ten children born to Namaypoke and his wife. Seven died during childhood. Only the eldest two were still living.

Anna’s sister, O-gah-bay-aush-eke, is listed on the form as Mrs. Tom Cobenas and recorded as living in Red Lake.2

Anna explained her sister Grace died only two years earlier in 1914. Grace had married a Canadian soldier named Philip Goodin. Anna mentioned they had two children.

“My father said the land should be divided into two parts, and the money into three; one third to my sister, one third to me, and one third to the children,” Anna Jones told Agent Dickens. The children were Grace’s daughter, Carrie, age 5, and son, Louis, age 3.

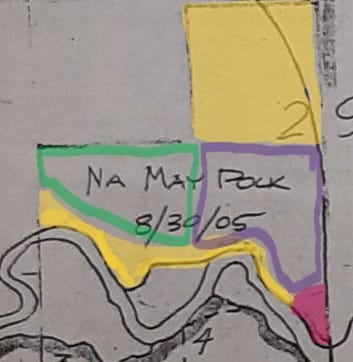

Dickens approved the distribution of Namaypoke’s funds with one-third ($1,878.16) going to his daughter Nay-nah-a-beak (Anna Jones), one-third to his daughter O-gah-bay-aush-eke (Catherine), one-sixth to Carrie and one-sixth to Louis Goodin. Of the original 113.95 acres in the allotment issued in 1905, a 7.27 acre parcel along the river front where he is buried and a 40 acre parcel in the NE quarter remained in Namaypoke’s name when he died in 1916.

Anna continued to reside in the house built for Namaypoke until her death in 1948. Roy Jones, who lived with his grandmother Anna in the house when he was a boy, remembers walking with her to the Warroad bank so she could cash her monthly check. He would write out her name on the back of the check, and his grandmother would mark her X next to it.

I’m grateful to Roy Jones for sharing his memories and personal copies of documents. The picture of how this allotment came to be and how parcels of it sold became much clearer. And these missing pieces promise answers to a lot of lingering questions about what happened to the rest of the allotted land since Namaypoke died.

“The ‘Grip’ Epidemic of the Winter of 1915-1916. Louis I. Dublin, Ph.D., Statistician, Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, New York City. American Journal of Public Health Vol. 6 (5):45-487. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1286854/pdf/amjphealth00093-0055.pdf

In other documents I have found her name listed as Catherine and Katie. I have also found her husband listed elsewhere as Stephen Cobinais rather than Tom Cobenas.

Curious what became of that seven acres? Thanks Jill for sharing all your learning.

I wonder how favorable Namaypoke was to the conditions that he would be paid in installments? Of course, you wrote earlier that "authorities" claimed he would not spend his money wisely. So it appears they were able to claim the conditions of his payment, which he clearly did not personally get to enjoy beyond the first $25.00.