Last week I reported finding that in 1903 Namaypoke marked an X next to his name on a legal document relinquishing 40 acres from his original 1897 allotment application. The Secretary of Interior did not approve and issue Namaypoke his allotment papers until 1905 when the Warroad School District required his signature for their purchase of a four-and-a-half-acre parcel from Namaypoke for $150.

This week I take a look at what happened next to his real estate.

Allotments of Indian reservation land could not be sold while they were held in trust by the federal government for a period of time, usually 25 years. In order to gain a clear title so as to sell allotment land, an Indian had to apply for a “fee simple patent” with the Bureau of Indian Affairs after meeting the terms and time requirements.

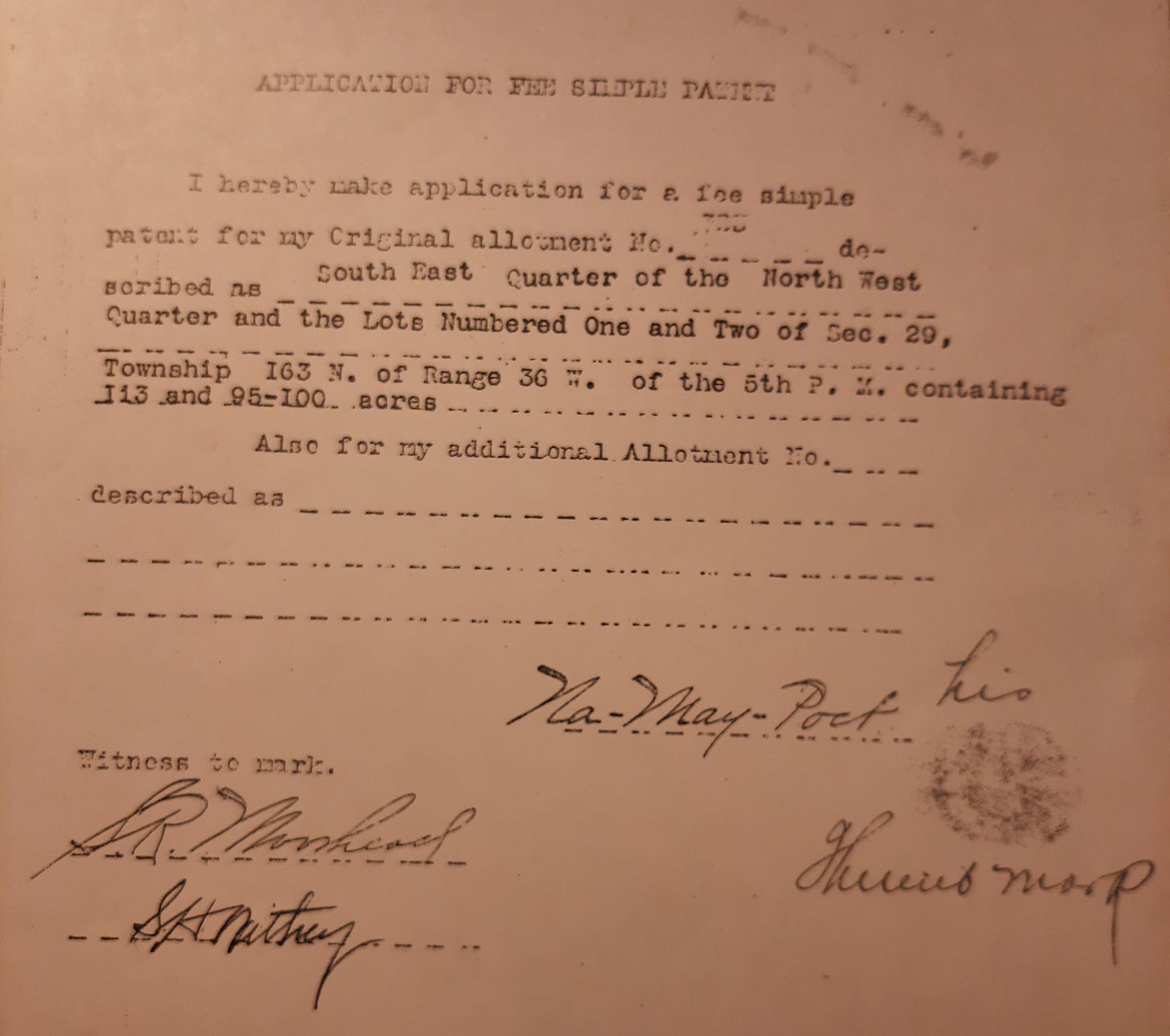

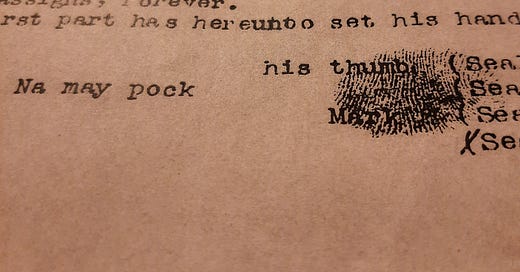

Only seven years after he received his allotment papers, Namaypoke submitted a “fee simple patent” application to Red Lake Indian Agency. I found it in a new batch of documents Namaypoke’s great-grandson Roy Jones mailed me. You can see Namaypoke’s thumbprint on it.

The 1912 application date leads me to wonder whether Namaypoke wanted to sell his land or if others wanted him to sell his land.

Walter F. Dickens was the Superintendent at the Red Indian Agency when Namaypoke’s application arrived on his desk in Red Lake, Minnesota.

Dickens rejected his request. This didn’t mean the Indian Agent prevented Namaypoke’s land from being sold. It meant the Agent wanted to prevent Namaypoke from selling the land to whomever he chose and from gaining access to unrestricted funds from the sale of his land.

Dickens wrote a lengthy report dated July 3, 1912, based on a visit to Warroad to supplement his denial of the application for a “fee simple patent.”

While I did not get to see Na-may-pock, he being away on a visit among the Indians on the Canadian side of the Lake, I am thoroughly convinced that he is incompetent to manage his own affairs. I based my opinion in this from the fact that he is a man about 70 years old, uneducated, inexperienced, does not speak the English language and as stated by one of the citizens of Warroad, if he was to get $10,000 for the land turned over to him without restrictions he would be broke in less than three months. This opinion is cooberated [sic] by the statements of the Mayor of Warroad, the Postmaster, the Editor of the Warroad Pioneer and in fact all parties from whom I inquired stated that he was incompetent and wholly incapable of transacting any business of this kind.

For the above reasons I recommend that his request for a patent in fee be denied.

Dickens laid the groundwork for a “deed of land of non-competent Indians,” which denoted an Indian’s inability to hold the title.

This legal form of deed restriction reflects the rampant paternalism toward Indians by white Indian Agents during the period of assimiliation. Dickens had the political authority to determine what was best for individual allottees as a federal employee of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Department of Interior.

Documenting non-competence meant Dickens would decide whether to sell Red Lake Reservation land, not Namaypoke. He came to appraise the land as much as assess competence.

Dickens observed during his visit to Warroad that the entire allotment could be sold “at a fair price.” He described the land as situated between the city on the east and the Highland Park residential subdivision on the west — central to future growth and development in Warroad.

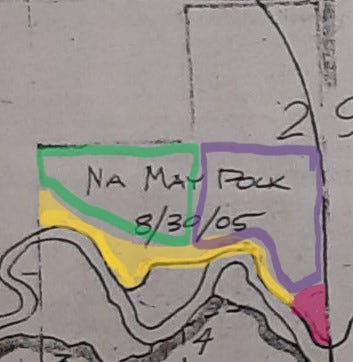

Namaypoke’s allotment is left of center on the map above, north of the Warroad River. To the west (left), James Friend Holmes had sold lots in Highland Park and to the east lay the heart of the commercial district and main streets of residential neighborhoods on the north side of the Warroad River.

When Dickens visited Warroad he observed “twenty odd families living on this allotment without legal lease thereon.” He described a scattering of houses constructed by squatters themselves. “The people who have built here are poor people and most of them built on the allotment for the reason that they were financially unable to buy a lot in the town site of Warroad…”

Dickens listed the parties on Namaypoke’s allotment who built homes on this land — from one-room shanties to houses he appraised at $600-$700 in value:

Martin Akre, Mr. Kofstad, Peter Smith, S. Salmonson, John Frolander, Pete Goulet, Andrew Lofgren, T. Allard, Mrs. Ed Evans, Gus Huerd, Mr. Carrier, A. Pouseps, Mrs. N. Whaley, Mr. Frutiger Jr., Joseph Servis, Cout Chase, Berghalf & Anderson, Wm. Begg, Mrs. Brooks, Warroad Creamery Co., Wm. St. Louis, Mrs. Servis, Albery Storey.

I found a picture postcard of Mrs. Whaley’s “shanty” on the Namaypoke allotment land in the digital collection of the Minnesota Historical Society.1

Not only were there families squatting on Namaypoke’s allotment land, but businesses, too. The Warroad Cooperative Creamery, he noted, represented an investment of $3,000. Dickens observed a lumber yard and saw mill, “the sawmill having burned on the morning of the day I arrived at Warroad, June 28 [1912].” He saw an ice house located along the river bank, a baseball field and a grandstand on the allotment land.

From his description, it is clear the allotment land was home to more than Namaypoke and his family. Poor whites and widows, Métis and landless Indians resided on this land. A lot of these families worked in commercial fishing, lumber, laying railroad tracks, farming — labor vital to the business interests and growth of the city.

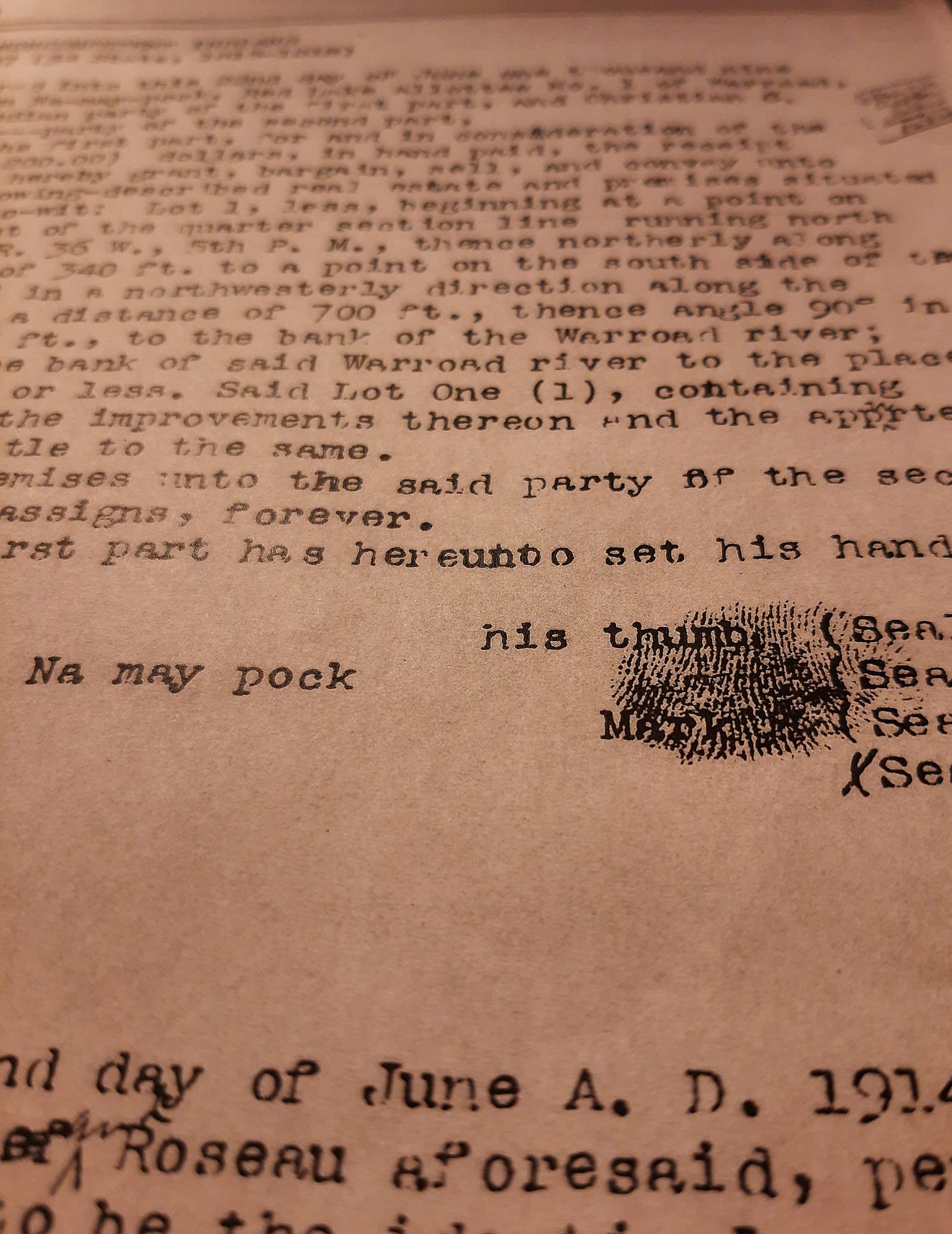

In August of 1914, Indian Agent Dickens acknowledged and approved the sale of two parcels of land in Naymaypoke’s allotment with “Deed of Lands of Noncompetent Indians.” One parcel of 27.29 acres sold for $2,200 and the other piece of 35. 4 acres — including all the improvements and squatters’ buildings upon the land — sold for $5,200.

This rough sketch2 above shows the $2,200 parcel outlined in green and outlined in purple is the $5,200 parcel where the creamery was located. The pink parcel in the lower right-hand corner is what had been sold for $150 to the Warroad School District in 1905. The riverfront acreage highlighted in yellow — approximately seven acres — is where Naymaypoke resided and where he is buried.

Both parcels were purchased by Christian Strander who offered the only bids. A Norwegian immigrant in Crookston, Mr. Strander was president of a large abstract and investment company in 1914 and had numerous financial and business relations with the City of Crookston and townsite companies across the state of Minnesota. At the time, he served as president of the Minnesota State Abstracters Association.

Strander likely acted on behalf of the Warroad Townsite Company. When the recorded deeds were certified on August 2, 1915, these two parcels of real estate went on the property tax rolls for the City of Warroad.

After completing the sale of Namaypoke’s land, Walter Dickens as Superintendent at Red Lake Indian Agency was required to file a report with the Department of Interior.

On page two, the report required an answer to this question:

In case but one [bid] was received, why in your opinion, was there no competition? Would the rejection of the sale and a readvertisement of the land be for the best interest of the Indian?

Dickens responded:

I do not think readvertisement of the land advisable. Local business men think the appraisement is high.

The last question at the bottom of page three, asked:

Is the land available for townsite purposes, and if so, what consideration was given such fact in making the appraisement?

His answer:

This tract is available and suitable for townsite purposes, due consideration being given the location when appraised.

On the last page, an explanation for why it is for the best interest of the allottee to sell the land is required.

This old man is an incompetent, unable to support himself or develop his allotment, which is valuable for townsite purposes.

As I reviewed these documents, what came to mind is the lyric from an old folk tune: “Some will rob you with a six-gun, and some with a fountain pen.”3

Minnesota Historical Society, Gale Family Library, Online Collection. Whaley’s first shanty, 1902. Locator number MR9.9 WR r4, Accession number YR1938.3848

This a rough estimate based on my reading of the deeds. I am neither a lawyer nor an expert in surveys of real estate. Professional verification would be appreciated. This remains subject to revision.

“Pretty Boy Floyd,” music and lyrics by Woody Guthrie.

This kind of deep research into local stories is really valuable. If this country ever chooses to engage in "truth and reconciliation" or gets serious about reparations, each bit of this history will be essential. I was also struck by how convoluted the legal claims can be. And what we have decided is "legal."

wow, Jill - you continue to work deeper into this history, peeling the onion. How wonderful that Roy Jones had these documents and that you have been able to add this to your research/discovery. I expect Namaypoke and the other Natives of the time, had no chance of really retaining their land, and there is no romanticized version; Namaypoke "gave" the land for a school, that makes sense anymore. Once again, hoping that, "when we know better, we do better" .