A Brief History of Buffalo Point First Nation Reserve in Manitoba

and its succcession of chiefs

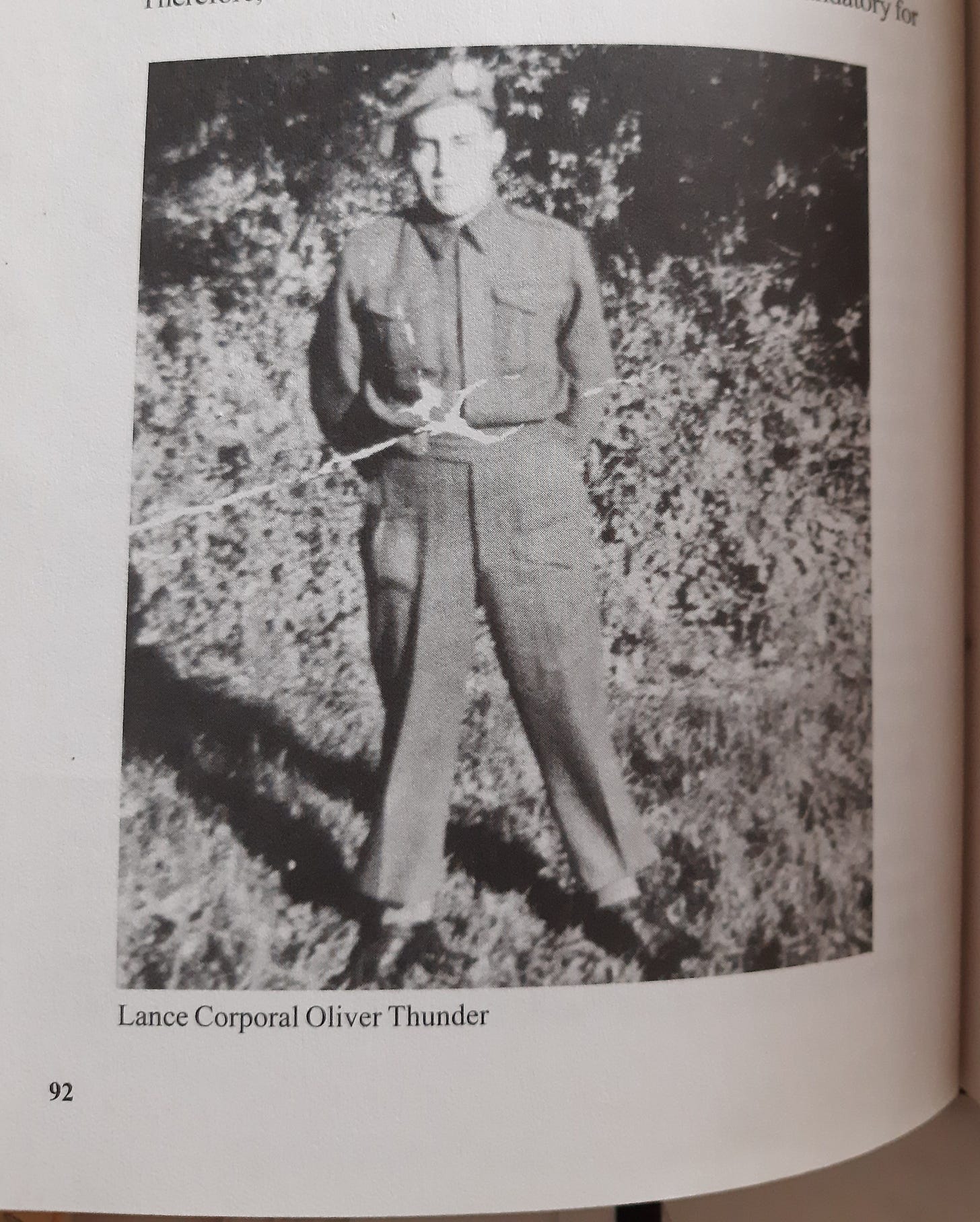

When Lance Corporal Oliver Thunder of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders died fighting in Normandy, France, on July 22, 1944, Buffalo Point First Nation in Manitoba lost its future chief.

Oliver Thunder was the great-great-grandson of Animikeese (Frank Little Thunder). Animikeese was the son of Chief Ay Ash Wash (1795-1899) at Buffalo Point and brother to Namaypoke and Kakaygeesick, who both lived in Warroad, Minnesota.

Since 1907, Oliver’s paternal grandfather Gaybayashquay, known as “Old Jim” Thunder, had been chief at Buffalo Point. Old Jim Thunder and his sons ran a sawmill and sold lumber and produced railroad ties for the Canadian National Railway. His eldest son, Tom, was eight years older than Warren, who everyone called “Shorty” even though he was more than six feet tall.

Canada didn’t formally recognize the First Nation Reserve lands surrounding Buffalo Point until 1930. Recognition had required residency and registration of tribal members.

The population of the Indian band on this remote peninsula of about 1,000 acres in the southeast corner of Manitoba had dwindled to a small group of 32 people, including Old Jim, his wife Molly, and their two sons, Tom and Shorty. The Thunder family lived in a big log cabin on the Reed River, about eight miles north of Buffalo Point and further inland off the peninsula.

Buffalo Point itself was without any year-round residents by 1927. No road access, no electricity, no telephone, no trading post, no postal service.

Members of the Cobiness, Handorgan, Lightning, Kakaygeesick, and other families in the band returned to Buffalo Point for the summer season and to trap or hunt in winter. But many had taken up residence in Warroad where their children attended school (after Tom Lightning had persevered in gaining admittance for his son John and other Indian students in 1925).

According to Thunder family lore,1 one day in 1935 an Indian Agent approached Sarah Thunder at the log cabin on the Reed River. The Agent told her that because she now lived on the Indian Reserve, her children would be sent to residential school.

Oliver would have been 14 years of age then and likely had already graduated from eighth grade. James and Catherine — Sarah’s children from her previous marriage to Fred Conover — were much younger. James was only five years old and his sister not quite four. Tom and Sarah had two more children, Dorothy and Frank.

In his book, Buffalo Point: Rising to a Higher Level, John Thunder claims his grandparents, Tom and Sarah, did not want to be separated from their children, so they moved to Middlebro, Manitoba. But Tom’s stepson James Irvin Conover attended Warroad School, not Middlebro.

There were other reasons to explain why Tom and Sarah Thunder didn’t live on the Reed River anymore. Changes in conservation regulations in Canada transferred timber rights from the tribe and disputes over reserve status for acreage along the Reed River sent Manitoba officers to evict Tom’s brother Shorty from his log cabin and it was burned to the ground in 1936. Logging commenced and the land disputes were not settled in court in their favor until 1989.

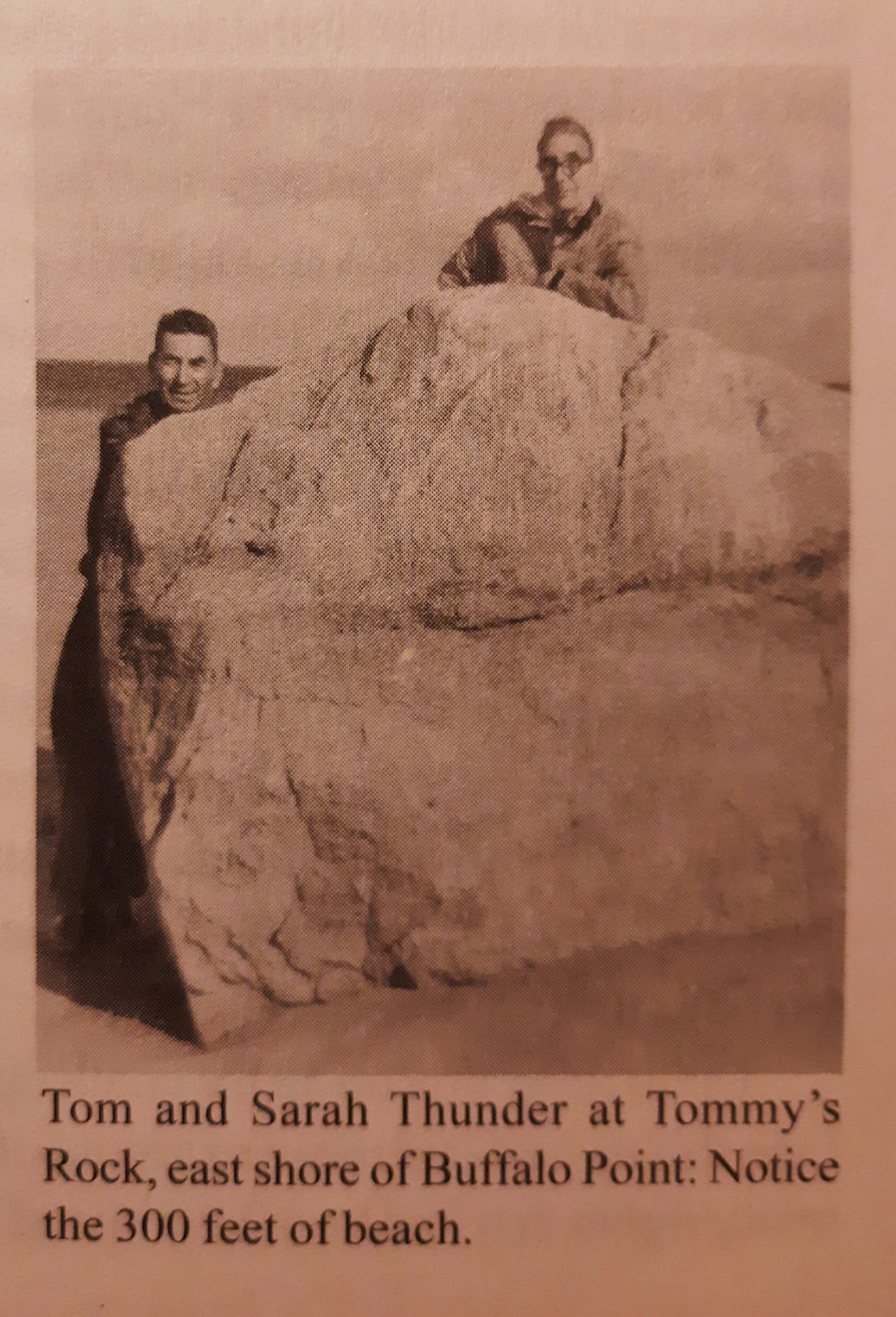

There is another reason Tom and Sarah weren’t living there. Water levels on Lake of the Woods were raised in the 1930s for hydroelectric power in Kenora, Ontario. This meant flooding at Buffalo Point; much of the Reserve became swampland. Wide sandy beaches were swallowed whole, and enormous sandbars washed away.

The Canadian government had finally granted reserve status to land they made largely uninhabitable.

As the war dragged on, Tom feared his younger brother Shorty might be drafted into military service. Instead, Shorty became chief in 1944, the same year Oliver died.

After the war, the tourist industry began to grow on Lake of the Woods. Sports fishing replaced commercial fishing.

By the mid-1950s there were several potential buyers of Buffalo Point who inquired of Indian Affairs in Ottawa how a sale might be arranged. In the mid-1950s the Manitoba Department of Natural Resources considered acquiring Buffalo Point and creating a summer resort. Without road access, the plan was put on hold. That is until construction started in April 1959 of the last stretch of highway between Middlebro and the border crossing to Warroad.

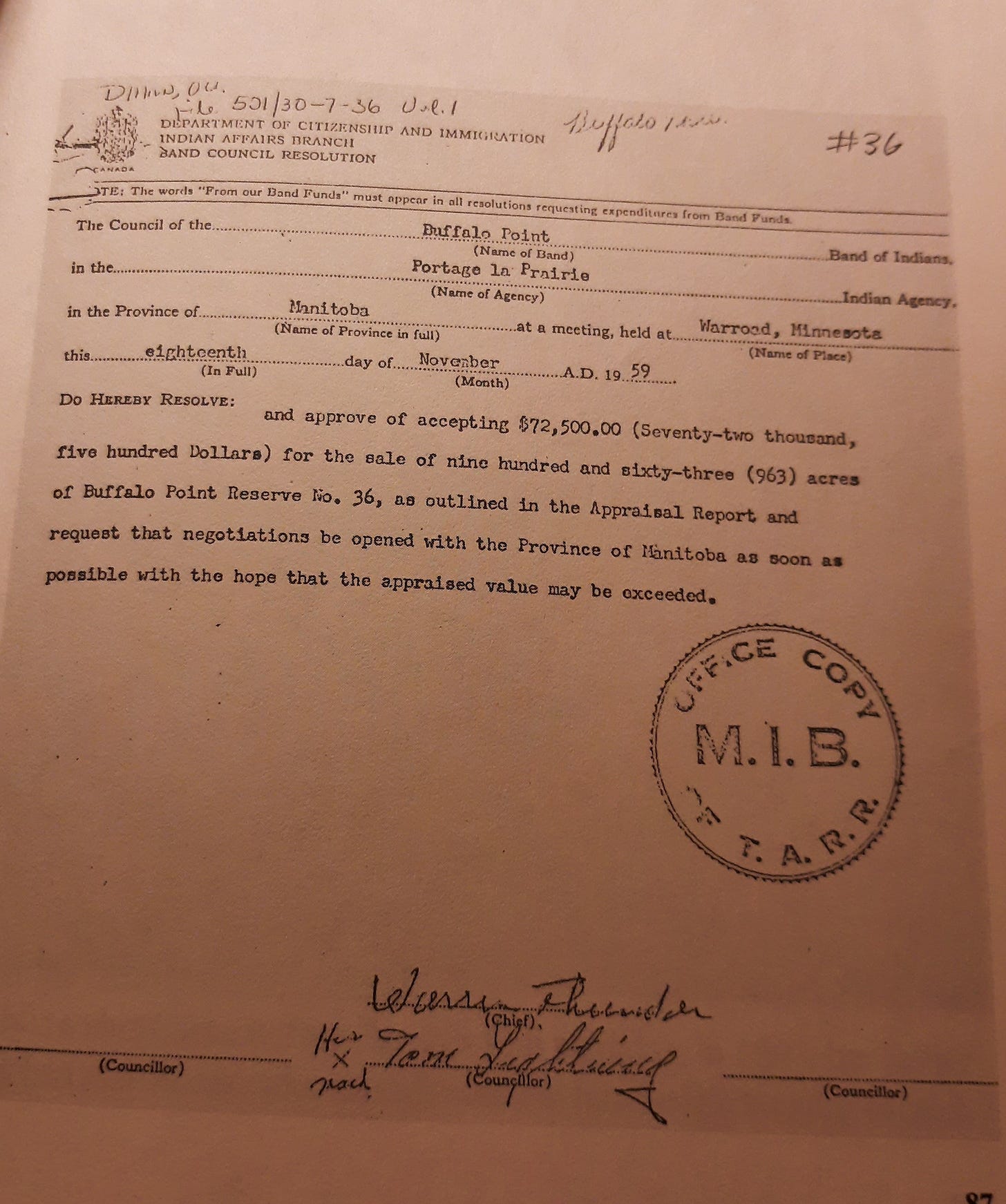

In order for the Canadian government to sell Reserve land, members of the band had to vote to surrender it. Chief Shorty Thunder convened a meeting in Warroad where most members lived. On November 18, 1959, band members ratified the surrender agreement and accepted a price of $72,500 for 968 acres.

Tom Thunder voted against the sale.

When the document was submitted, the Department of Indian Affairs rejected it because the vote was held in Warroad, Minnesota, and not on Buffalo Point Reserve in Canada.

This delay in the procedural process of selling the Reserve to the Canadian government gave the band time time to reconsider. Why couldn’t they open a summer resort at Buffalo Point?

It was the summer of 1967 when Chief Shorty Thunder received notice the Canadian government intended to sell Indian Reserve lands at Buffalo Point and Reed River.

The Superintendent of Indian Affairs informed him there had been no record of the Buffalo Point First Nation Indian band for several years as all the members had left. The Superintendent claimed the land belonged to the Crown and would be used as a provincial park.

This was news to Chief Shorty Thunder. He called together a tribal council meeting in October of 1967 to discuss the dire situation. Facing the threat of losing the land, Shorty knew he needed help. His health had begun to fail him.

Shorty had never married and had no children. Tom Lightning’s son, John, was away serving in the US Navy.

Tom Thunder wrote to his stepson, Jim, who was serving in the United States Air Force and stationed in North Africa working as a military police officer. Tom asked him to return home to help them save their sovereignty.

Jim left his military job in 1968 and moved back to the village of Middlebro, Manitoba, with his wife and young children. And in 1969, a tribal council meeting was held and a resolution passed:

We the band members of the Buffalo Point Band request that James Thunder be recognized as the legal representative of the Band in all matters pertaining to the development of the Buffalo Point Reserve. We further request that funds be made available so that James Thunder, his wife, and family can be maintained until such time that this is no longer required.

Warren Thunder (Chief), Tom Lightning, Ethel Lightning, Doris Thunder, James Thunder, Eddy Cobiness (Councilors).

Shorty Thunder submitted his resignation as chief and James Irvin (Jim) Thunder became chief.

For the first time, leadership passed to someone who was not a direct descendant of Chief Ay Ash Wash.

Reasserting Buffalo Point as a First Nation Reserve was complicated by the fact that Indian Agency funding was determined by the number of tribal members living on a Reserve. The new chief moved his young family to a trailer home in Middlebro and Buffalo Point received its first funds from the Department of Indian Affairs in 1970. The check was for $1,200.

Shorty Thunder’s health continued to decline with a series of heart-related incidents. He died of a heart attack in his favorite cafe in Warroad on May 22, 1970.

Tom’s stepson Jim Thunder served as chief until 1997 when he retired and his son John assumed the role.

Jim Irvin Thunder died on December 31, 2024.

Jim returned from Vita to his home in Buffalo Point on his 94th birthday, November 13th, 2024. His family is grateful to have been able to celebrate his birthday and Christmas with him at home, and that he was able to spend his final days at the place he loved and dedicated his life to, Buffalo Point.2

As of April 2025, there are 143 registered tribal members, and 58 of them live on Buffalo Point First Nation Reserve where John Thunder is chief.

Today Buffalo Point Resort offers an 18-hole golf course, a marina, a luxury hotel, cottage rentals, and a campground. The modern history of Buffalo Point Resort is a longer story for another day. But here’s a short video produced by Travel Manitoba in 2020 about Buffalo Point on Lake of the Woods which captures the beauty of this place.

John Thunder, Buffalo Point: Rising to a Higher Level 2012: 67.

I really enjoyed watching the video. Thanks for including it.

For me, reading these small local histories illuminate the larger history of native people in the US and Canada.