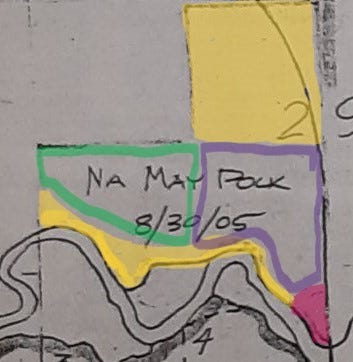

An extension on Namaypoke's allotment

+ easements = heirs couldn't sell land but it could be taken

When Namaypoke died in 1916, two parcels of his allotment had aready been sold to Christian Strander of Crookston, Minnesota, in 1914 by Red Lake Indian Agent Walter Dickens on behalf of the “noncompetent Indian.”

I had wondered whether Strander, president of a large abstract and investment company, purchased the land on behalf of the Warroad Townsite Company.

In the records Namaypoke’s great-grandson Roy Jones recently sent me, I found evidence to confirm my suspicion. Strander didn’t sell the land, he gave the two parcels to “The Public” in a “Deed of Dedication” recorded on August 20, 1915.

The only bids for this land had been from Strander. The Warroad Townsite Company likely provided Strander with the sum of $7,400 for the sale of the two parcels. By dedicating the land to the city of Warroad, Strander successfully converted Indian land into private property and onto the tax rolls.

When Namaypoke died, two parcels of land from his 1905 allotment remained in his estate. A seven-acre piece along the bend in the Warroad River, and a 40-acre quarter section.

What also remained after Namaypoke’s death was the 25-year deed restriction on his allotment. This meant the seven-acre and forty-acre parcels could not be sold before 1930 without approval from the Department of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs.

On June 26, 1930, President Herbert Hoover in the midst of the Great Depression issued Executive Order 5383, which extended the term of the allotments issued to Namaypoke and Kakaygeesick by another 10 years. This meant the land could not be sold before 1940.

Why had President Hoover extended the terms of allotments? I discovered in a list of Executive Orders issued during his administration that Hoover had done the same thing for multiple cases involving reservation lands across the country.

Why by Executive Order? Hoover had endorsed and enforced assimilation policies — allotments and boarding schools. It would be four years later — as part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal — before Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934, introducing notions of self-determination. It had only been 1924 when the Indian Citizenship Act gave Indians the right to vote.

In 1929 Hoover was elected with his vice-presidential running mate, Charles Curtis, on the republican party ticket. Curtis was Senate majority leader from 1924-1929, but had first been elected to the US House of Representatives at the age of 32 in 1892.

A member of the Kaw Nation of Kansas, Curtis was a Topeka attorney whose first piece of authored legislation extended the Dawes Allotment Act in 1898. Curtis encouraged the transfer of land ownership from tribal nations to individual Indians. The Republican administration knew the likelihood of Democrats in Congress agreeing to extend the Dawes Act further were slim to none.

Hoover’s Executive Order in practical terms meant the heirs of Namaypoke’s estate could not sell the land for another decade. Perhaps this protected the value of the real estate from being sold for pennies on the dollar when the stockmarket crashed in 1929. Or perhaps this kept his heirs in poverty during the Depression when they might otherwise have been able to borrow against the value of the land. The extension by a decade of the terms of the allotment meant the heirs could not gain clear title to their land as private property.

The prohibition on heirs selling the land didn’t mean some of it wouldn’t be taken.

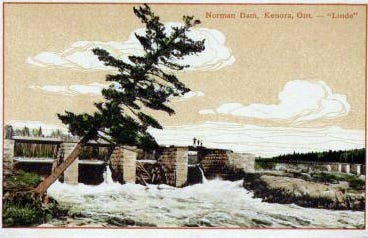

On June 23, 1930, the District Court of the United States for the District of Minnesota issued a decree. The federal government granted itself a flowage easement for various tracts of land in Roseau County, including the allotments of Namaypoke and his brother Kakaygeesick. It claimed “the right and privilege” to raise the level of Lake of the Woods in compliance with treaty agreements with “his Britanic Majesty in respect of the Dominion of Canada.”

The US government prioritized its treaty obligations with Canada in the case of these two Red Lake allotments over the treaties it had signed in 1837, 1854, and 1855 affirming the rights of the Ojibway in Minnesota to their lands, to public waters, and to hunt and fish. Raising the water levels to permit the production of hydroelectric power for the city of Kenora, Ontario, affected everyone living near Lake of the Woods.

The flowage easement by the federal government applied to everyone on the ceded lands of Red Lake Reservation. These two allotments were treated the same as any other land claim or deed when it came to the government taking land. However, when it came to selling land the government prohibited it.

Hoover signed the 10-year extension on the allotments on June 26, 1930, three days after the court decree granting the flowage easement.

When lake levels rose, the Warroad River flooded. On the seven-acre parcel of land where Namaypoke lived, several hundred feet of riverfront were lost to flooding.

The Kakaygeesick allotment on the lake shore changed irrevocably when they raised water levels. Of the original 102.6 acres, all but six remain under water to this day.

In a document labeled Miscellaneous Record No. 178, Roseau County, there is a list of payments to be made for this flowage easement. The document is signed by John B. Sanborn, US District Judge, on the 5th of October, 1931, in St. Paul, MN. I did not find Kakaygeesick listed, but I did find an award of $495 recommended for Easement No. 411 which lists the owners as “the unknown heirs of Na May Pock.” It is as yet unknown whether such a payment was ever made or to whom.

A right-of-way easement for the highway which went through Namaypoke’s allotment came after the flowage easement. In February of 1936, the State of Minnesota Department of Highways paid $125 to the Office of Indian Affairs in Washington, DC, for 4.4 acres of the allotment for State Highway 11. The highway had been built in 1934.

State Highway 11 still runs north across the Warroad River along the eastern edge of Namaypoke’s allotment and curves to the west, rounding off the northeasternmost corner of the 40-acre parcel.

When the train depot in Warroad opened in February of 1900, Canadian Northern Railway had taken 3.2 acres from land reserved for Namaypoke. Members of the Warroad Townsite Company and Warroad School District recognized the land as his since at least 1897 when they assisted him in the preparation of the allotment application with his thumbprint.

I could not find official documentation of the railway easement in the early 1900s and continue to search. I have found some on properties nearby which were not settled and recorded until well into the 1930s.

In 1940, the Field Service of the Office of Indian Affairs, United States Department of Interior sent a “Letter of Information Regarding Indian Allotments” to the Register of Deeds of Roseau County, Minnesota. It explained that “the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which was accepted by the Red Lake Indians, indefinitely extended the existing trust upon any Indian lands governed by this Act…Therefore the trust periods on the above allotments have been indefintely extended.”

I understand this letter to mean that any sale of lands from the allotments issued to Namaypoke and Kakaygeesick would require the approval from Red Lake Indian Agency as it became considered “trust land” or part of the reservation in 1934.

Encroachment never stopped. It received a 10-year extension. It became easements which took more land for the railroad, the highway, and the lake.

Yet, the land remained in the county register of deeds as Indian land until 1954.

That is when the story of what happened to the rest of Namaypoke’s allotment gets mighty interesting. And more complicated. It’s where I’ll pick up the paper trail next time1.

Disclaimer: It has come to my attention that you may have received an email from me or seen a message on the app that I am giving you a $5 credit toward a paid subscription. Uffda. My apologies. My newsletter continues to be free and I had no knowledge Substack sent out such messages. Since Substack earns a small percentage from paid subscribers who use their platform, they are promoting their platform but making it look like I am first giving you money but instead asking you to pay for this free newsletter. I am not asking for paid subscriptions and want to make this material widely available as a public history project. I am grateful to the subscribers who have decided to help defray the costs of research and have paid for a subscription without me asking. I apologize to anyone who received one of these messages from Substack and, like me, found it irritating and unnecessary.

Please keep sorting this stuff out! It's documenting something that's happened in a lot of places. The complexity of the various processes is part of the strategy of encroachment and it's these "duck bites" that have provided a "death of a thousand cuts" for tribal sovereignty.

You had a sentence in this that jumped out at me. "Encroachment never stopped." I would move your sentence into the present and the future: "Encroachment has never stopped." Sadly too many of our "manifest destiny" citizens believe as long as they "win", taking property and damaging lives of indigenous peoples is acceptable.